2022 was a bird-filled year for me! I got 86 total lifers; I photographed 75 and recorded 23. I had 40 songbirds, 17 shorebirds, 9 parrots, 7 waterfowl, 4 gamebirds, 4 raptors, 1 cormorant, 1 grebe, 1 pigeon, 1 rail, and 1 hummingbird.

I’ve organized this article to describe my interactions with these species so I can remember my initial thoughts about these birds and share some helpful tips with you if you are looking for or at any of these beautiful birds.

So, without further ado, let’s dive in.

286. Purple Finch (Haemorhous purpureus). 01 January 2022. Kankakee County, Illinois, United States.

My dad and I started off the new year birding in the freezing snow. I was very surprised by the activity while we were out. The weather on New Years’ Day 2022 was a balmy 29°F (-1.67°C) with 20-mile-per-hour winds and snow. Even with this sharp weather, the warblers, chickadees, kinglets, robins, woodpeckers, and other birds were going about their morning like usual. One of my goals was to start the year off with a lifer, and the Purple Finch was the obvious target. This species had been spotted on and off throughout Kankakee County, and I was picking through House Finches, trying to find one. Finally, in the freezing cold, I spotted a group of House Finches with four other birds that were clearly brighter and stayed just at the edge of the main flock. The birds didn’t stay too long and took off after a few minutes to search for more berries, but I finally got my Purple Finch.

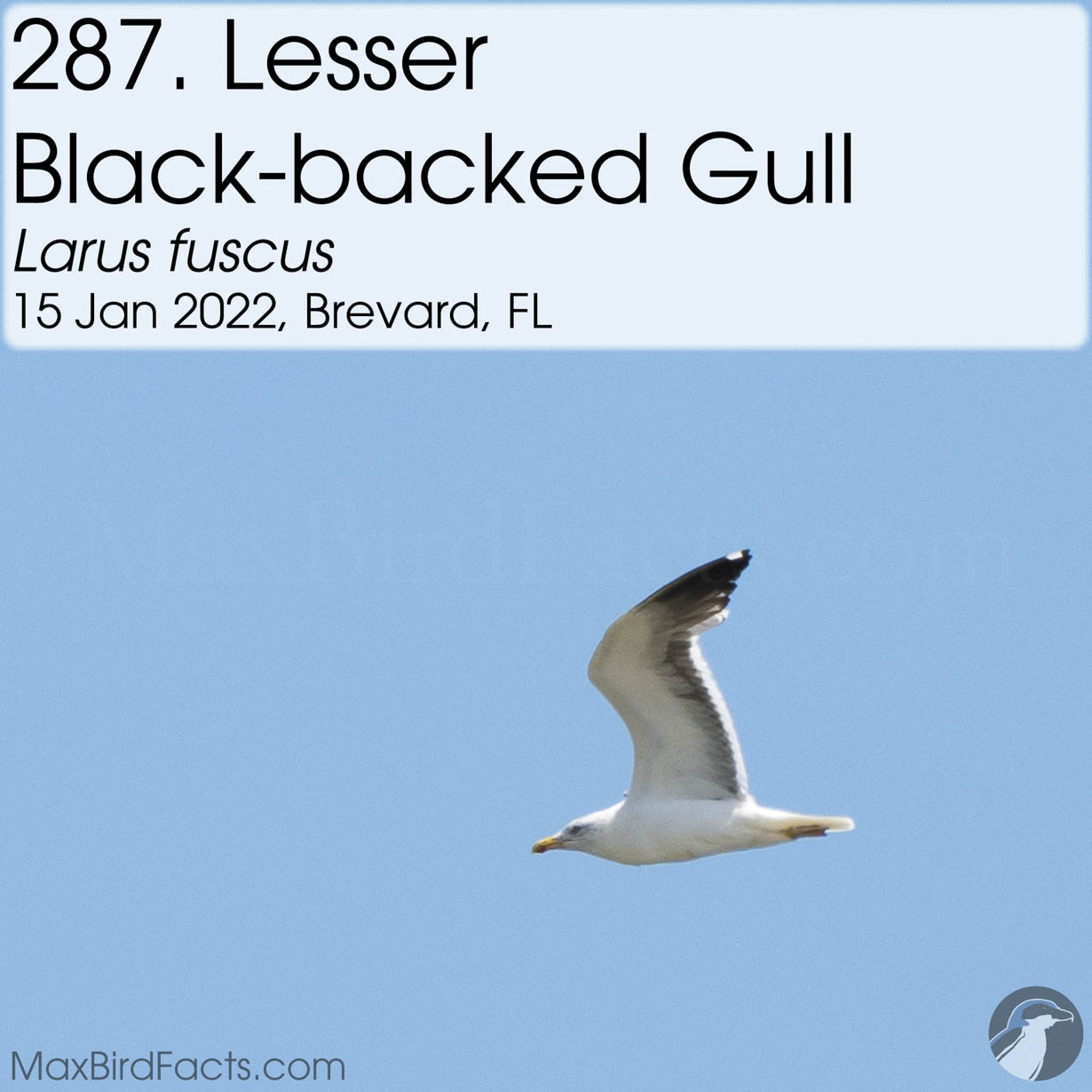

287. Lesser Black-backed Gull (Larus fuscus). 15 January 2022. Brevard County, Florida, United States.

Gulls and other shorebirds are definitely not my strong suit, so I spent a lot of time learning them this year. During winter, we receive a lot of gulls from up north, like this Lesser Black-backed Gull or LBBG. Their close relative, the Great Black-backed Gull or GBBG, travels down with them and can be confusing to distinguish.

The best field ID markings for adult wintering birds I’ve found are the size and location of the white spots on the tips of the bird’s primary flight feathers. In this photo, we can see the spots are small and not all the way to the tip, which is a good mark for the LGGB. The GBBG has much larger white markings that usually cover the very tips of the wings.

The real tricky identifications come from the multiple plumage stages gulls have. Thankfully, there are ways to tell the difference between first winter Lesser and Great Black-backed Gulls, but I’ll save that for a future article!

288. Long-tailed Duck (Clangula hyemalis). 21 January 2022. Brevard, Florida, United States.

The Long-tailed Duck was a great find at the start of the year, though it wasn’t easy. Pulling off the bridge heading into Merritt Island, we stopped and scoped the water looking for this rare bird. Thankfully, it was far enough away from the hundreds of Ring-necked Ducks and Lesser Scaup that it was obvious when we finally saw it. This duck is a very rare visitor to Florida, and its range usually ends along the South Carolina coast and the northernmost edges of Georgia.

289. Clapper Rail (Rallus crepitans). 21 January 2022. Brevard, Florida, United States.

Rails are tricky to photograph, and the Clapper Rail is no exception. This recluse stays separate from their cousins, King Rails, by preferring brackish coastal waters rather than inland freshwater. However, these rails are pretty boisterous with their calls. Unfortunately, I’ve only heard this bird and have yet to photograph one. Still, adding a bird to my life list by ear is rewarding in its own right.

290. Stilt Sandpiper (Calidris himantopus). 21 January 2022. Brevard County, Florida, United States.

Shorebirds, like the Stilt Sandpiper, can be challenging to even the most experienced birders. The Stilt sticks out a bit with its thicker downswept bill and its tall dull yellow legs. Shorebird identification still throws me off from time to time. The Greater and Lesser Yellowlegs are two species the Stilt Sandpiper loves to flock with, and they can look surprisingly similar. However, keep the Stilt’s downswept bill in mind, and you will be able to pick it from the crowd.

291. Marbled Godwit (Limosa fedoa). 21 January 2022. Brevard County, Florida, United States.

This massive sandpiper was a real treat to see. My first sighting of this shorebird was at a great distance, but its enormous, slightly upturned bill was an excellent identifying feature. Thankfully, I got much closer and made some fantastic photos while a gorgeous Marbled Godwit visited the Florida Keys Hawkwatch while we were down there this October, which is the bird in this image. The gradation of the bill’s black tip to the light pink base is a gorgeous feature I couldn’t appreciate on my first encounter with this species.

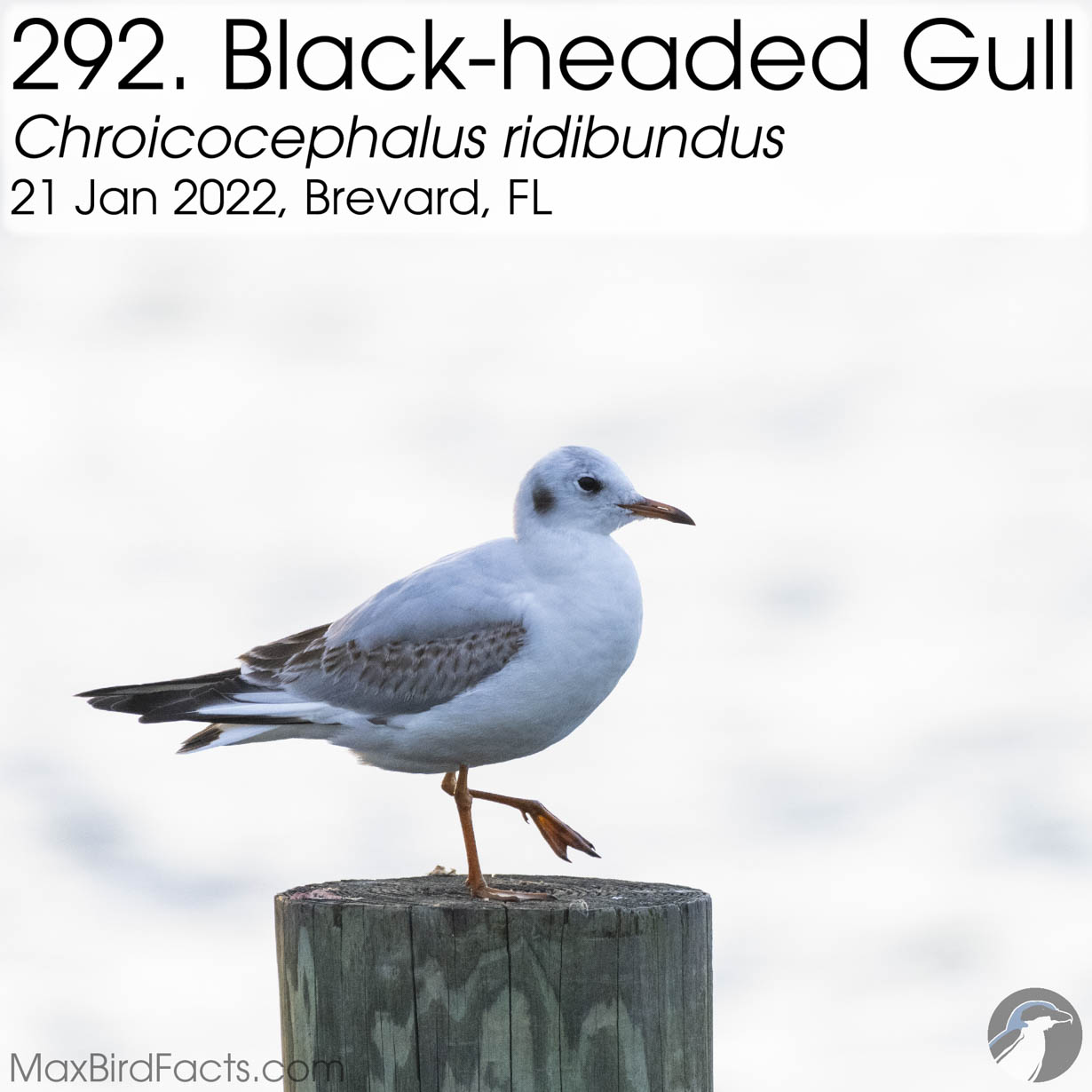

292. Black-headed Gull (Chroicocephalus ridibundus). 21 January 2022. Brevard County, Florida, United States.

The Black-headed Gull was a major score in the first month of this year! This bird had been hanging out behind a restaurant for a few days by the time my dad and I could make a trip out there and photograph it. This gull must have been blown way off course because their normal range ends around North Carolina, but there are spotty sightings of this species down to French Guiana in South America.

Unfortunately, it looks like this bird had an injured left leg since it would hang limply away from the body rather than tucked in or standing on it. Thankfully, people spotted this individual in the area through to April, but it hasn’t been listed since then. I hope this gull joined up in a mixed flock and headed back north during the spring migration to meet with members of its species in their more typical range of New York to Newfoundland.

293. Red Knot (Calidaris canutus). 22 January 2022. Pinellas County, Florida, United States.

This year I learned the importance of excursions to different regions and habitats around the state. So, watching some of the rare bird alerts and lists coming from the west coast of Florida, my dad and I started compiling areas to hit to find new species, and oh boy, we got some.

The Red Knot was the first of five shorebirds we listed and photographed very well at Fort De Soto Park. These sandpipers and plovers really tested our identification skills. Specifically, with the Knots, we were looking for a straight, relatively short black bill, bulky body with a white belly and fine barring on the sides.

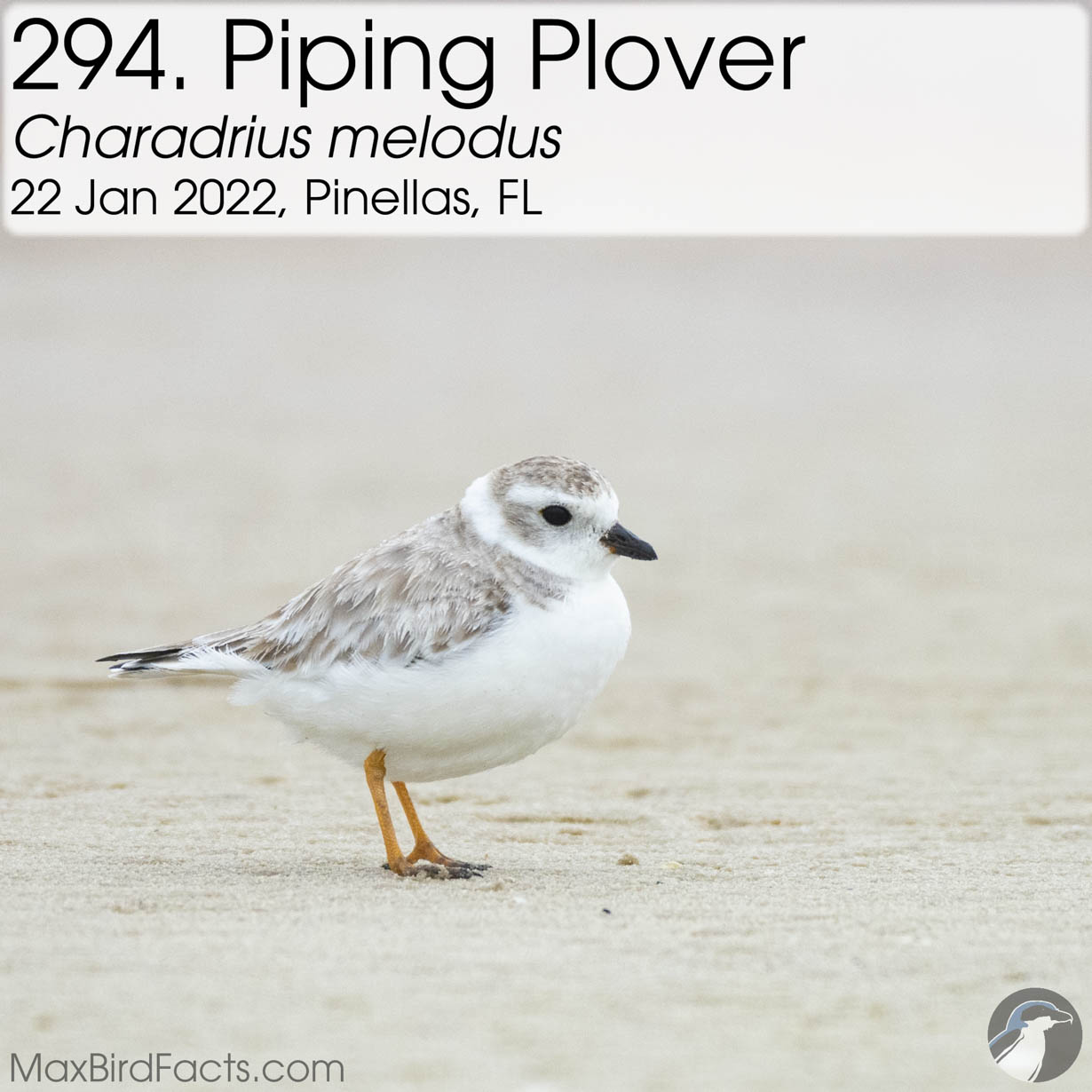

294. Piping Plover (Charadrius melodus). 22 January 2022. Pinellas County, Florida, United States.

The second shorebird lifer from our Fort De Soto trip was the Piping Plover. These little plovers would completely disappear in the sand when they stopped moving; their coloration perfectly matched the terrain. The identifying marking we were looking for on this species was its leg color, which we can see is a lovely bright orange. This is a stark contrast to the dull gray legs of the nearly identically sized Snowy Plover, the crown jewel of the Fort De Soto trip. A few other markings to look for on a Piping Plover would be the compactness of its beak and the orange at the base of the beak on breeding adults. However, the most readily apparent field marking we stuck to was the leg color, which worked perfectly for us.

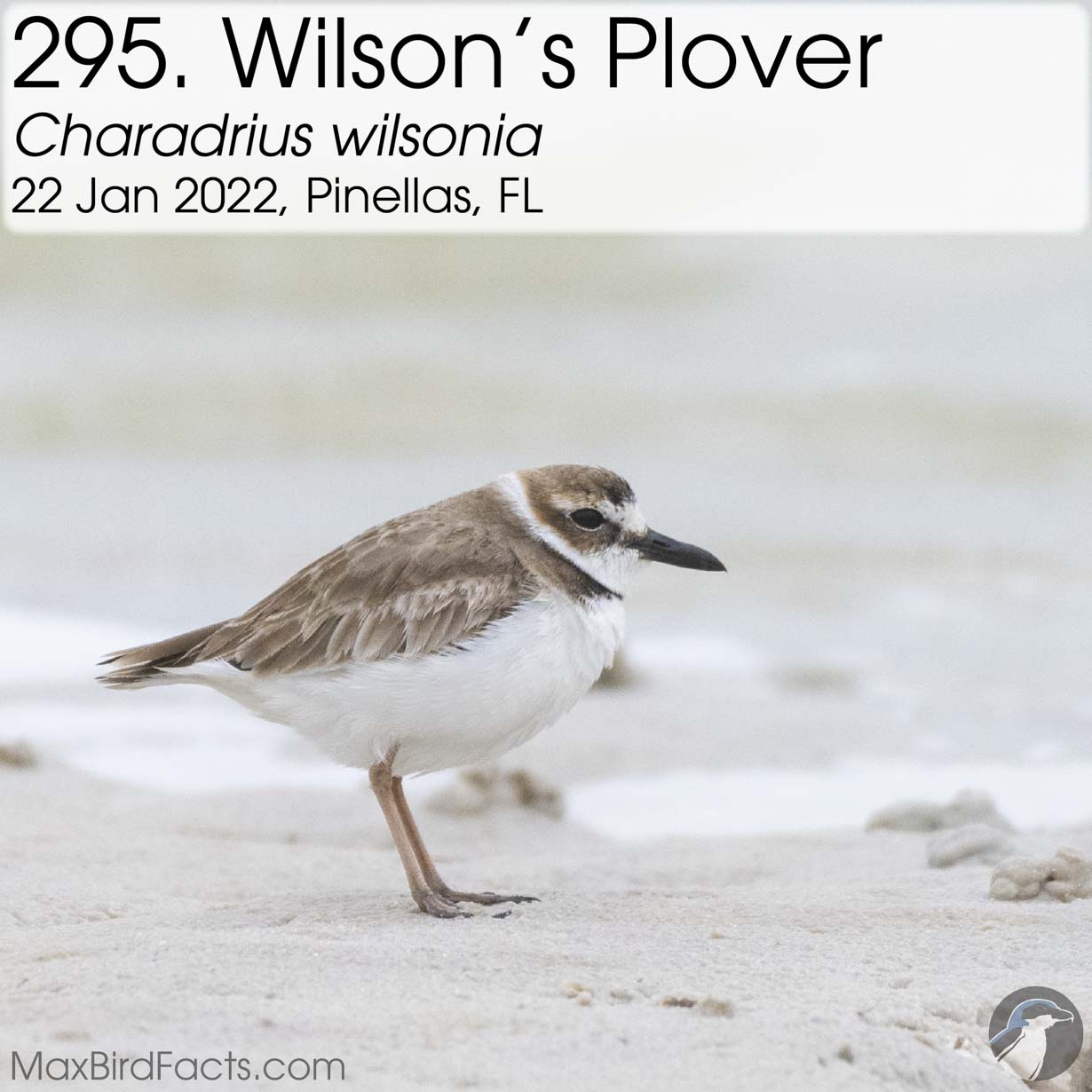

295. Wilson’s Plover (Charadrius wilsonia). 22 January 2022. Pinellas County, Florida, United States.

The Wilson’s Plover was strikingly larger compared to the Semipalmated, Piping, and Snowy Plovers it was associated with. Its dark brown plumage, long black bill, and fleshy-colored legs all made it stand out from the crowd at Fort De Soto. Surprisingly, like many other shorebirds at the park, these plovers were not afraid to allow us to get close. I’m not sure if this was because it was a chilly morning and the birds were just trying to stay out of the wind and keep warm or because they were more acclimated to people not trying to chase them down. Either way, this boldness allowed us to make some really great photos of these migratory birds!

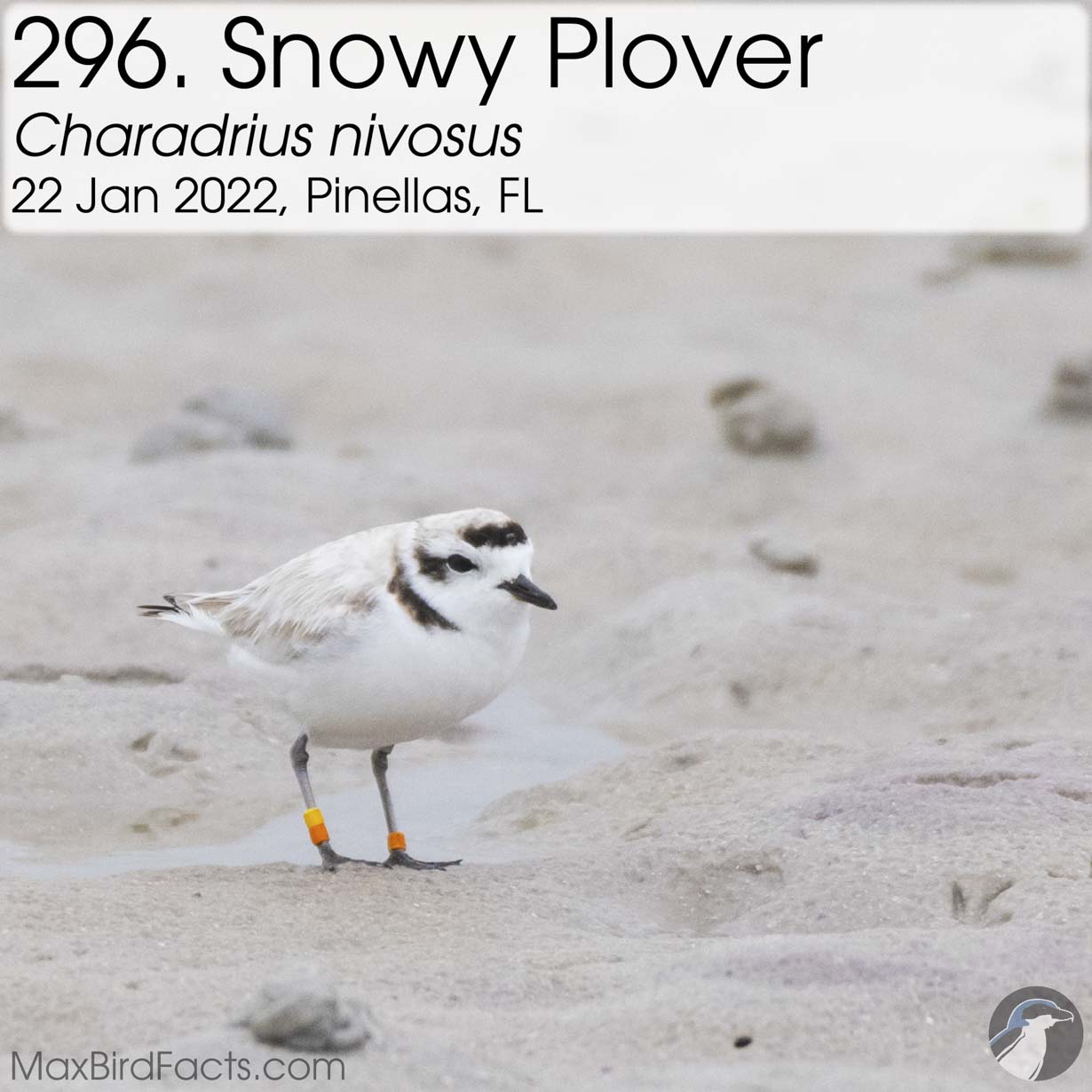

296. Snowy Plover (Charadrius nivosus). 22 January 2022. Pinellas County, Florida, United States.

The Snowy Plover was the main goal for my dad and me on our Fort De Soto excursion, and we saw eight individuals! Four of these little plovers were banded, and I was able to report them to the Florida Shorebird Alliance. Looking at the Florida Banded Bird Resightings Facebook page, I found out all four of these plovers were named: Sage, Shalimar, Soyo, and Thistle.

The bird in this image is Soyo, a male Snowy Plover banded in 2021 at Outback Key, not far from where we saw him a year after his banding. Bird banding is incredibly important to research. The colorful bands help people easily differentiate individuals in flocks, allowing for more accurate data collection. If you see or photograph a banded bird, please try to get it reported to the appropriate facility. I have an article on my website that links to several areas to submit banded bird sightings, and I am constantly adding more species as I find out where they need to be reported to!

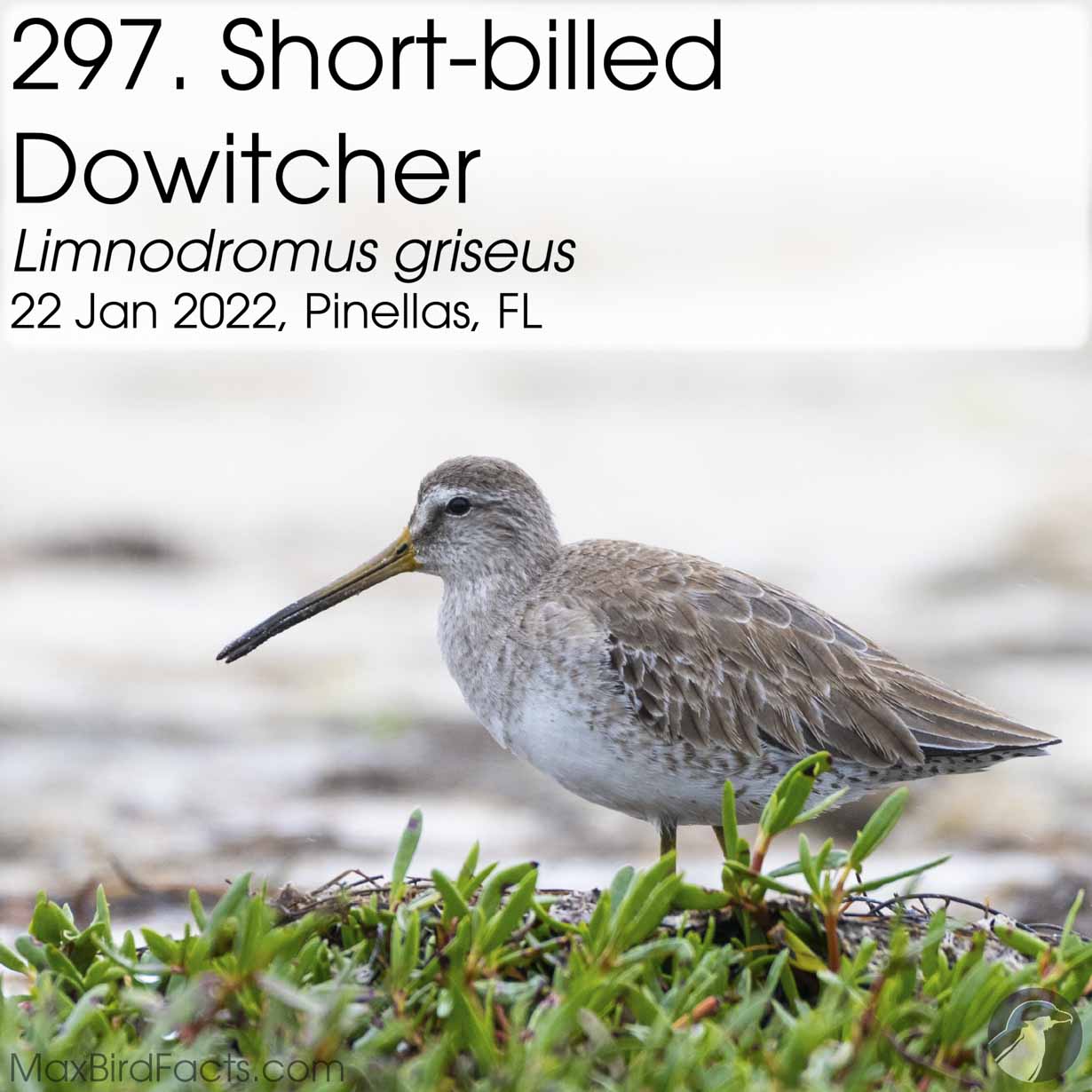

297. Short-billed Dowitcher (Limnodromus griseus). 22 January 2022. Pinellas County, Florida, United States.

Dowitchers are challenging to distinguish them from each other. Thankfully, the Short-billed Dowitcher is much more abundant on the coastline than their cousins, the Long-billed Dowitcher. Yes, the Short-billed has a shorter bill, and their legs are a duller yellow than the Long-billed. However, it is hard to discern this if both species aren’t standing together. Still, one of the best ways to verify which species you are looking at is through your ears. The flight calls of the Short-billed Dowitcher are notably lower-pitched, and a feeding flock will rarely make a sound. On the other hand, their Long-billed cousins are much more talkative while they eat, and their flight calls are incredibly high-pitched.

298. Red Junglefowl (Gallus gallus). 13 February 2022. Seminole County, Florida, United States.

The Red Junglefowl jumped on my list following eBird’s new method of counting domestic types. I’ve listed Red Junglefowl (Domestic type) on a dozen lists. None of those counted on my life list until going to Key West in October, where the wild type roams around the streets. However, eBird updated how they account for domestic kinds in early November 2022, which jumped the Junglefowl up over 50 places on my list. This was interesting to see how quickly my life list could switch around due to the current way species are measured. Either way, I’m glad I can say I’ve marked a chicken off as a lifer this year!

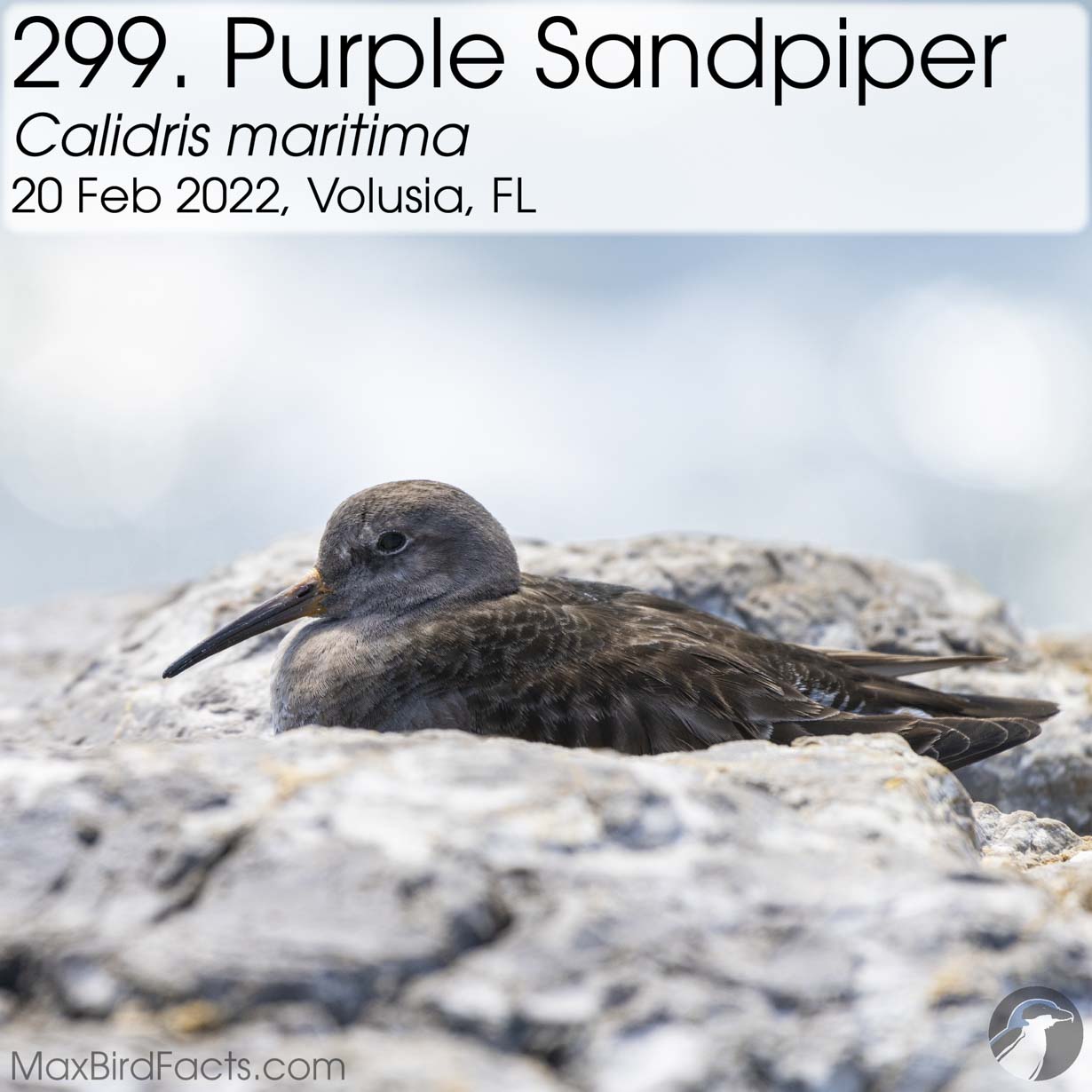

299. Purple Sandpiper (Calidris maritima). 20 February 2022. Volusia County, Florida, United States.

The Purple Sandpiper was a really luckily timed bird. Walking out to where this sandpiper had been listed before, a Ruddy Turnstone landed on the path directly in front of my girlfriend and me. We joked that it would show us the way to the Purple Sandpiper, but it actually did! The turnstone scurried down the path, took flight, and landed on some rocks a few yards away. When we caught up with it, the turnstone had landed just next to three Purple Sandpipers hunkered down on the warm stones. These rare sandpipers were completely fine having us sit and watch them, and they would occasionally lift their heads and open their eyes to check on us. It was a fantastic experience and a super great find!

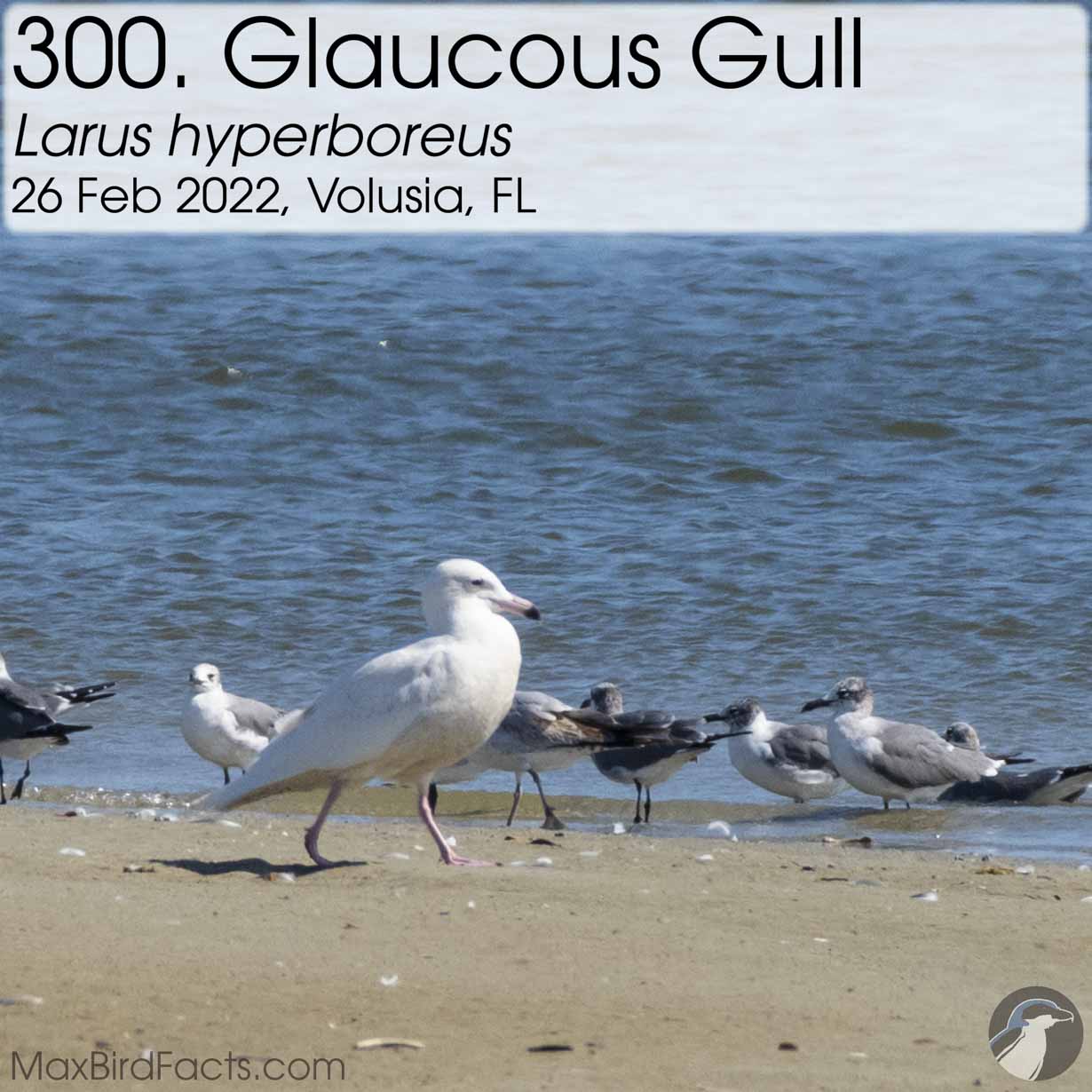

300. Glaucous Gull (Larus hyperboreus). 26 February 2022. Volusia County, Florida, United States.

The Glaucous Gull is by far the largest gull I’ve ever seen. How this massive, snow-white bird dwarfed the Laughing Gulls surprised me that it took as long as it did to find. Looking out at a sandbar covered in shorebirds from boat docks, this enormous gull completely disappeared among the much more common wintering species. However, once we did spot it, it was hard to take our eyes off it. My parents and I walked to a residential area where we thought we could have a better look at the Glaucous, and sure enough, my mom was able to get on a resident’s porch, and we had a superb view of this rare gull.

301. Iceland Gull (Larus glaucoides). 26 February 2022. Volusia County, Florida, United States.

Gulls might be the trickiest bird for me to identify. The Iceland Gull is one of several species that all look almost identical, with some very minor differences. Compared to the Herring Gull, the Iceland is slightly smaller, has a shorter bill, and has much lighter wingtips. The Iceland’s bill is also pinker near the base in all stages, but most during their first two winter plumages.

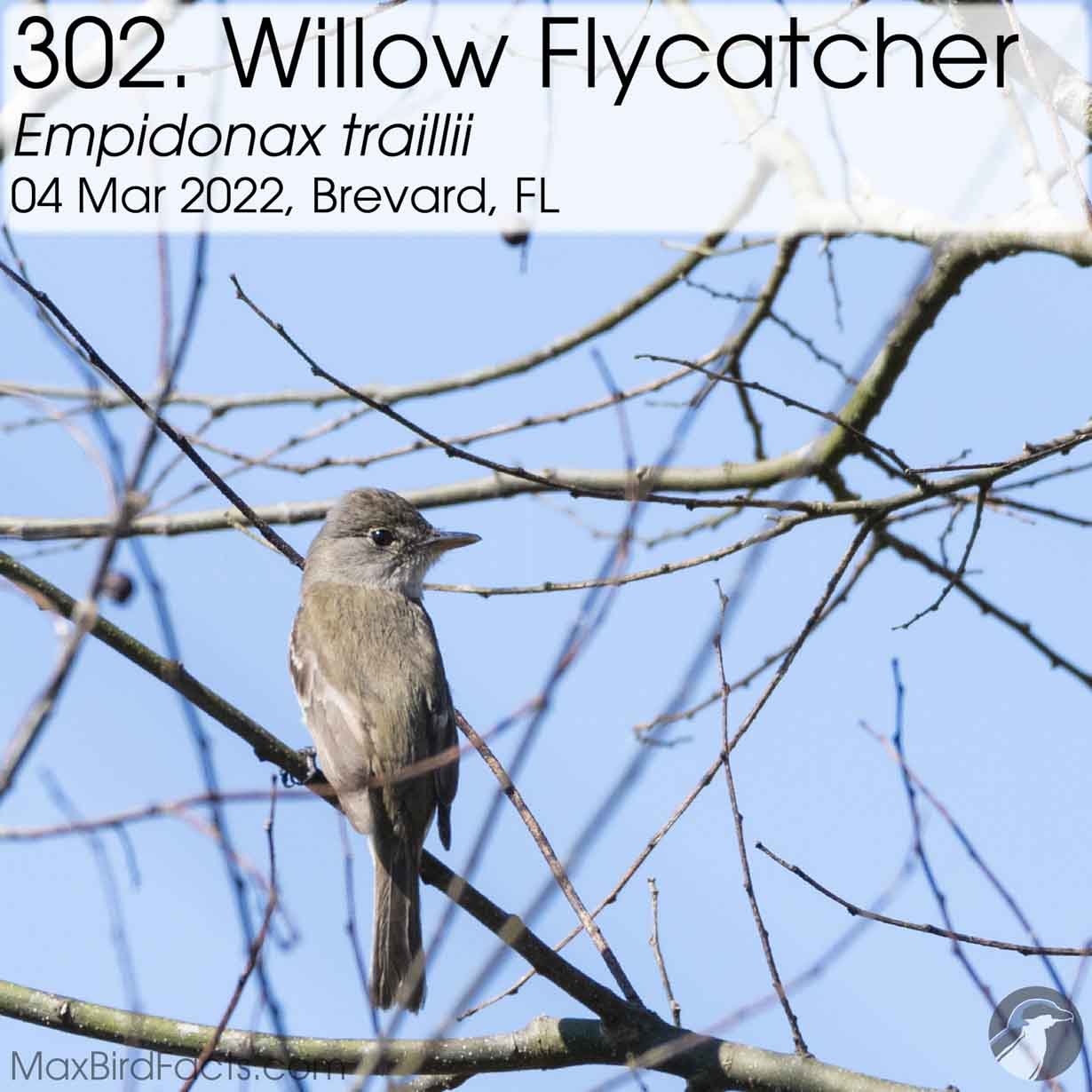

302. Willow Flycatcher (Empidonax traillii). 04 March 2022. Brevard County, Florida, United States.

Nothing’s better than a birthday lifer! I watched this Willow Flycatcher on the rare bird alert for a couple of days when my parents asked me what I wanted to do for my birthday. My immediate response was to try and collect some of the rare birds on the central east coast. We got three out of four targets but only photos of the Willow.

Tyrant Flycatchers are my dad’s favorite family of birds, and I can easily see why. Every time I’ve photographed these avians, I’ve felt like they have a conscious curiosity about why I am watching them. And this was the same case with this Willow. He seemed curious as soon as we spotted him, making small calls and fluttering from branch to branch to see different angles of us. I’m so happy to have shared a few minutes on my birthday with such a rare and beautiful bird.

303. Red-throated Loon (Gavia stellata). 04 March 2022. Brevard County, Florida, United States.

My second birthday lifer, but it was unfortunately too far in the harbor to photograph. Looking through the scope, I found the loon bobbing in the waves. It would become visible just long enough to see its much whiter face and lack of a collar that Common Loons sport in their nonbreeding plumage. This was my first time really pushing the limits of a scope, and I had to relocate the loon several times when I pulled back from the eyepiece. I’d love to get a nice photo of this bird someday, so maybe a trip to Alaska is in order.

304. Ruddy Shelduck (Tadorna ferruginea). 08 April 2022. Marion County, Florida, United States.

Sitting on the back porch with my dad, watching songbirds flutter in the branches through my binoculars, two large ducks fly directly overhead. I’m still kicking myself for not having my camera handy, but we could note the wing’s distinctive dark tail and trailing edge, ruddy color of the body, and pail head and wing coverts to make a positive ID on Ruddy Shelducks. Luckily enough, there is a residential group of these introduced Anseriformes a few miles away, and in the direction they flew over. Thankfully, since then, I have had a handful of opportunities to photograph these Old World ducks.

305. Yellow-throated Vireo (Vireo flavifrons). 09 April 2022. Marion County, Florida, United States.

Often heard, rarely seen, and even rarer to photograph, the Yellow-throated Vireo was a significant accomplishment for me this year. Their scold call is arguably the best to play if you are trying to pull in a mob of songbirds. Unfortunately, this vireo tends to stay high in the branches and concealed in the leaves, making their cousin, the Blue-headed Vireo, seem like an exceptionally cooperative subject in comparison.

At first glance, the YTVI could be written off as a Pine Warbler due to its brilliant yellow head and breast and prominent two white wing bars. However, when taking more time to look at this bird, the head is notably larger and rounder than a warbler’s, the eyes appear darker and more prominent, and most of all, the bill is much more substantial. The “vireo bill” has been my go-to field marking when trying to know which type of songbird I’m observing. Vireos have a much broader, robust bill with a prominent hook at the tip.

306. Acadian Flycatcher (Empidonax virescens) 09 April 2022. Marion County, Florida, United States.

Another flycatcher for the year! The Acadian Flycatcher is a challenging bird to spot. Like many other Empids (the short name for the genus of small tyrant flycatchers), these tiny tyrants are very reclusive and tend to stay deep in the brush. Their calls and songs are the best way to distinguish them from their cousins, which all look very similar.

An interesting tidbit I learned when researching these birds is their genus name Empidonax translates from Greek to mean “gnat master.” I have always loved learning about the meaning behind the scientific binomial names since they can glean a lot of information the taxonomist thought while studying the animal. However, maybe because of the size of the Acadian, this taxonomist didn’t believe it could rule over any insect greater than a gnat, unlike their larger relatives.

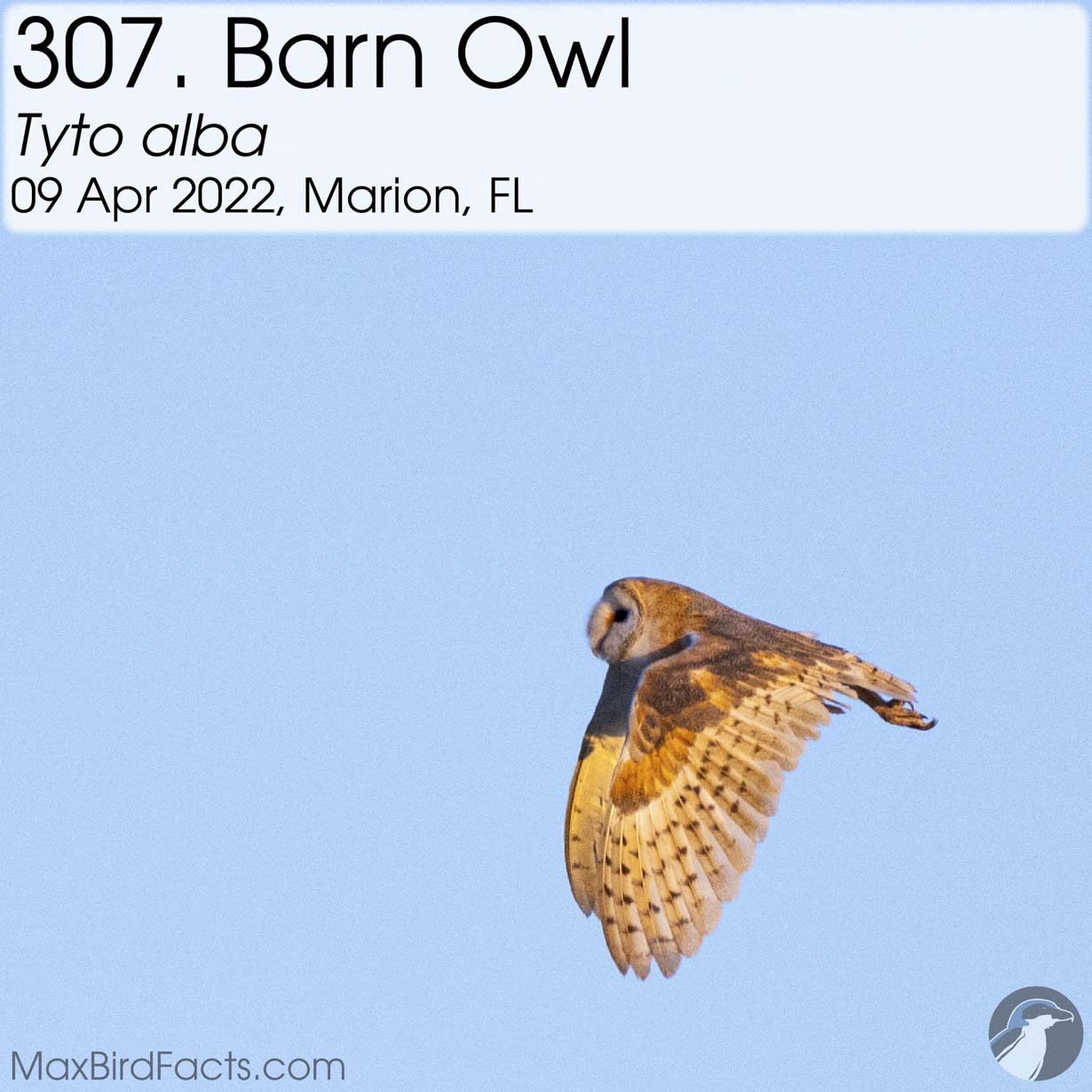

307. Barn Owl (Tyto alba). 09 April 2022. Marion County, Florida, United States.

I still can’t believe the sheer luck I was able to witness this beautiful nocturnal predator. Through a Marion Audubon member, a small group of us could go onto private property where two Barn Owls had been consistently seen. Once we got to the building, we split into two groups. My group went around the side of the building, and as I adjusted my settings for the low light, one owl shot out of the open doors, and it was too fast for me to get a photo. However, one of the people there was able to spot the second owl still perched, so I repositioned to get a shot as the bird flushed, and I was able to get a few decent images.

We saw where this bird landed in a pasture across the street. So, my dad walked out to the tree while I stayed on the side of the road to photograph it when the owl flew out, and it worked just like we had planned. The owl took off from its hiding spot and was illuminated by the setting sun as it flew to another tree to await nightfall. I’m so grateful for this beautiful adult’s cooperation and for allowing us to observe and photograph it.

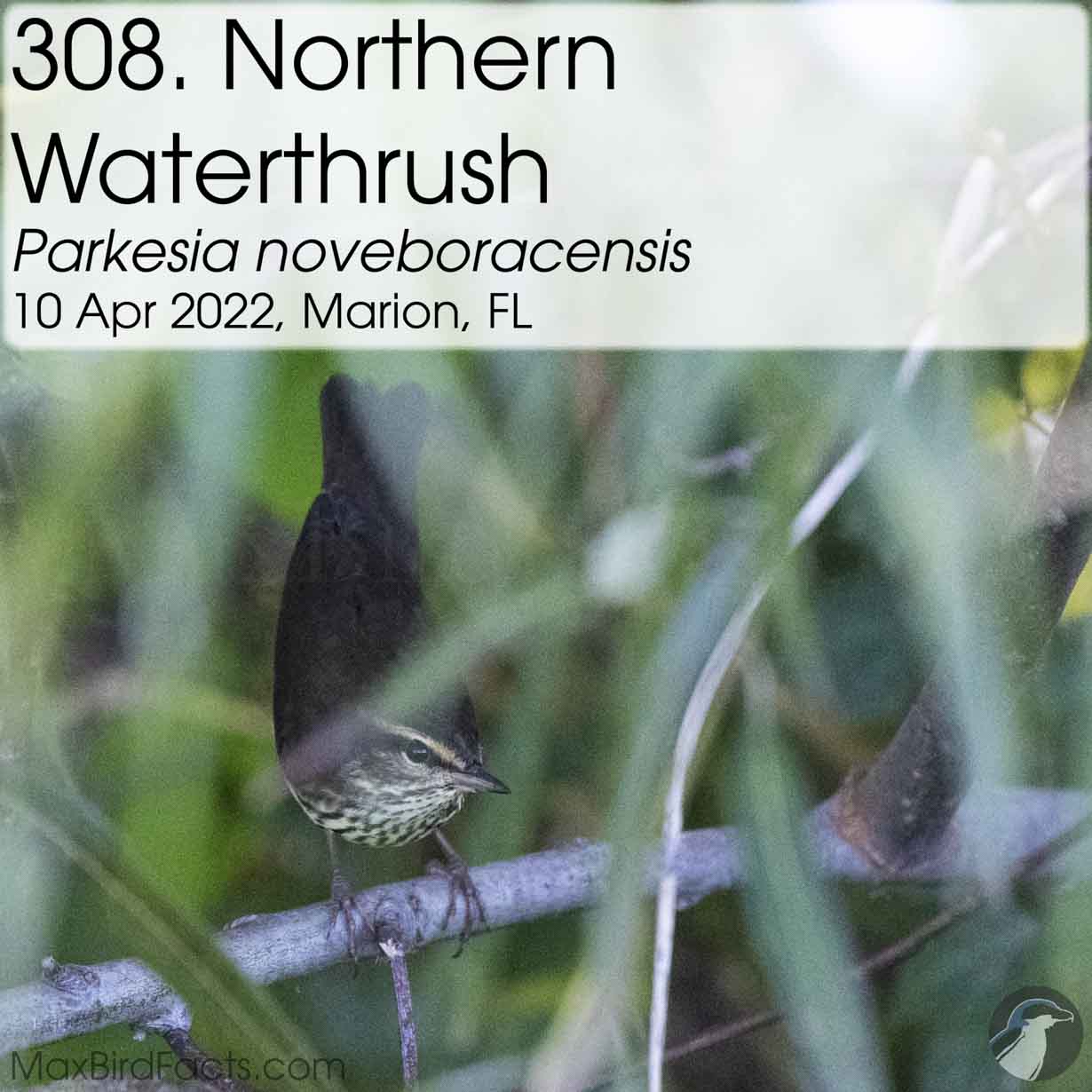

308. Northern Waterthrush (Parkesia noveboracensis). 10 April 2022. Marion County, Florida, United States.

Like many birds this year, I had to give up my original rule for lifers to only be listed if they were photographed. The first Northern Water I had this year was just a simple call, not a feather to be seen. Thankfully, later during the fall migration, I picked up the call again while photographing a Yellow Warbler nest site, and I finally got my first glimpse. I found out these waterthrushes tend to stay low and very deep in brush, with very moist to flooded ground below. I also discovered they responded almost instantly to pishing and would readily come in if you practiced patience. However, they are highly skittish; even the slightest movement would cause them to dart to a new perch.

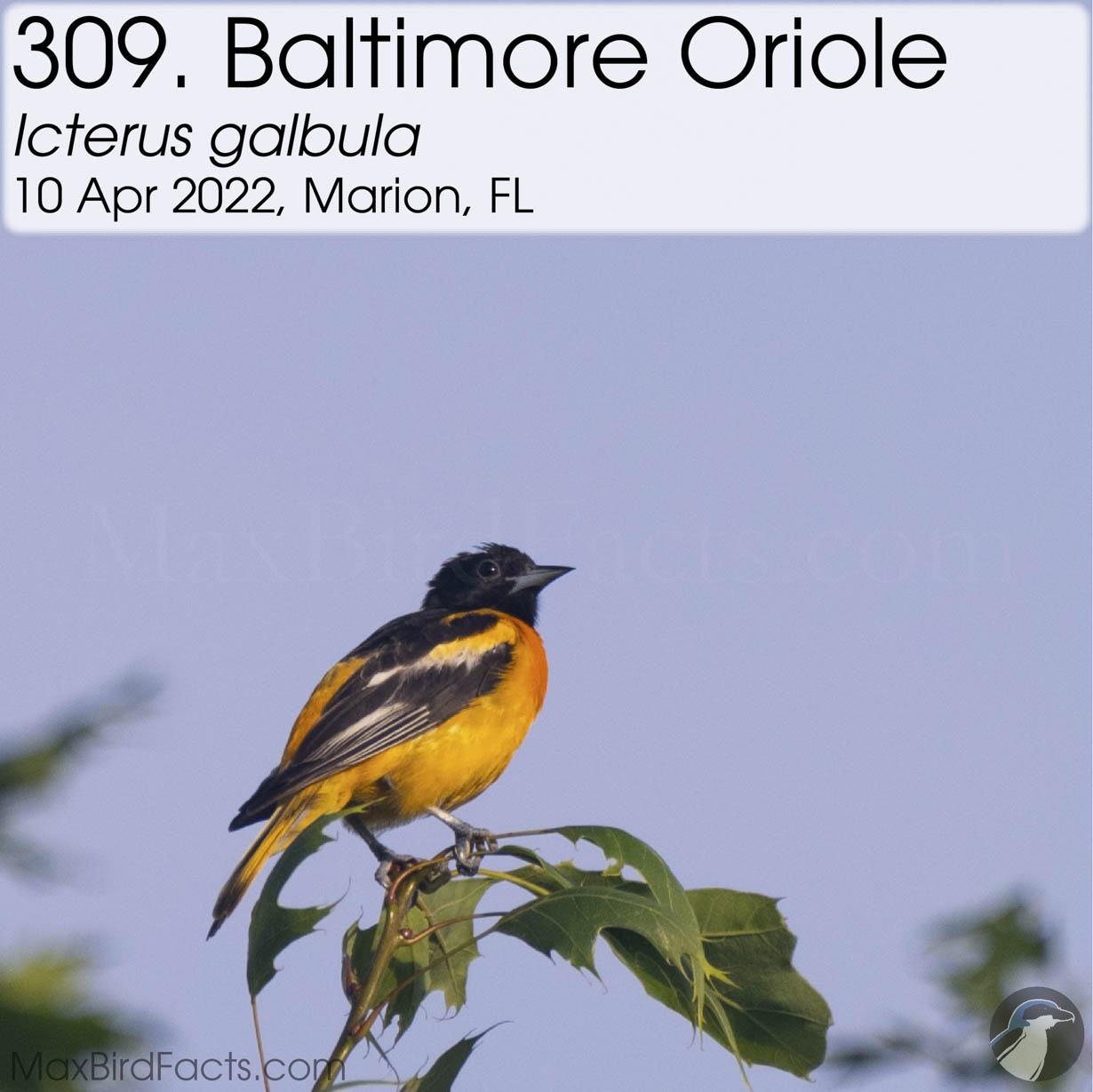

309. Baltimore Oriole (Icterus galbula). 10 April 2022. Marion County, Florida, United States.

A bird I’ve wanted to check off for a long time, and I finally have this year. The Baltimore Oriole is a stunning example of how brilliant North American blackbirds can be. These Icterids can still hide incredibly well, despite their vibrant plumage. Male birds seem to respond well to pishing but rarely come into the open to openly scold the birder.

Outside of the breeding season, these birds revert to a reclusive lifestyle again and are pretty hard to photograph well. Thankfully, during the summer in Illinois, my dad and I were able to photograph several gorgeous adult males displaying their exquisite aspect. One of these occasions was right as we stepped out of the car; the male pictured here was perched at the top of a tree singing his heart out. This was most likely to signal his availability to females or challenge any males to stay out of his territory. Either way, he made an extraordinary subject to photograph!

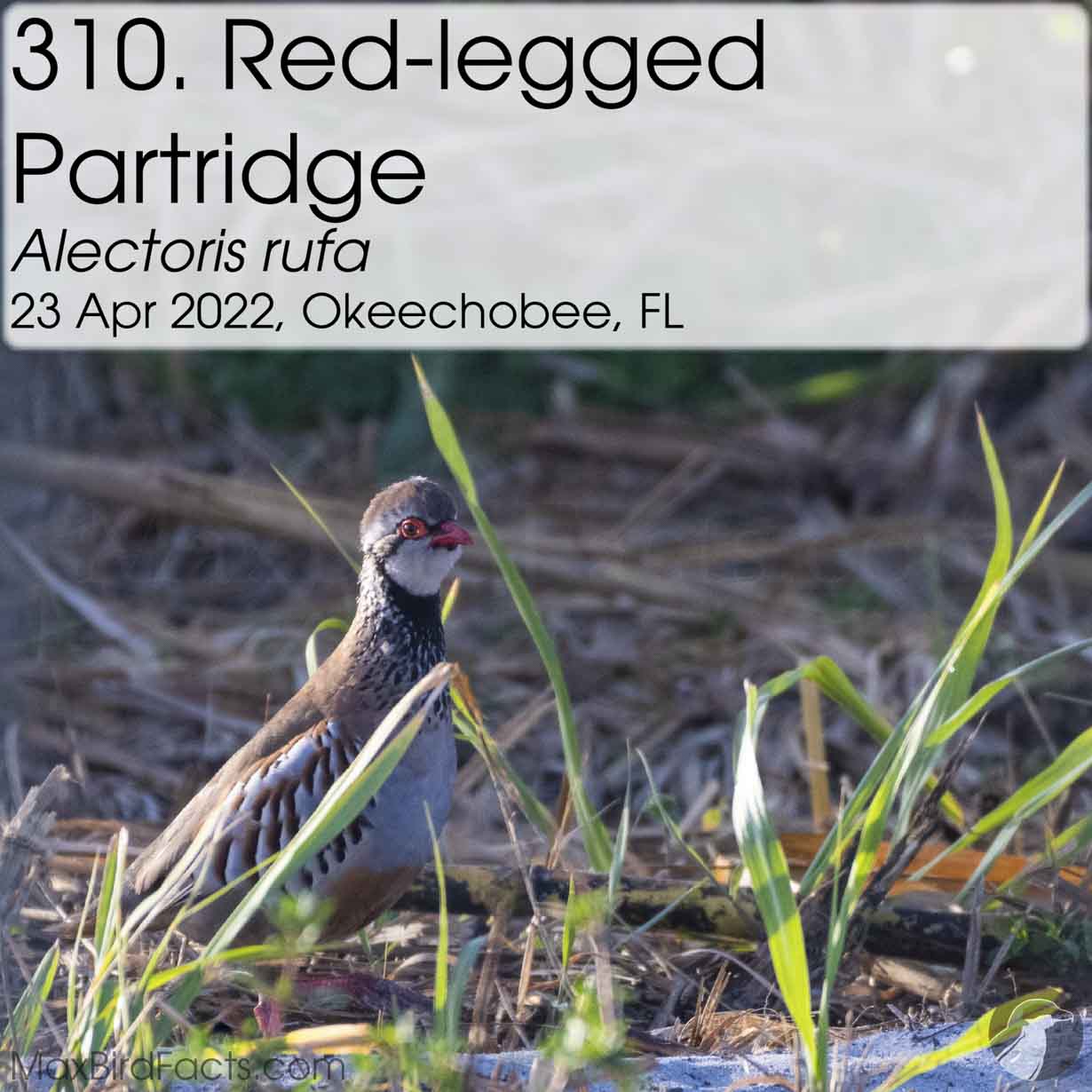

310. Red-legged Partridge (Alectoris rufa). 23 April 2022. Okeechobee, Florida, United States.

This past spring, I planned a trip to South Florida to find as many new species as possible with my girlfriend, Kayla. The first stop on our birding bonanza was to find extremely rare and localized Red-legged Partridges. The problem I faced while planning this stop was this species hadn’t been reported for almost three months, so I wasn’t entirely confident it would still be there. However, when we pulled onto the road these partridges had been reported on a few months previous, we were greeted with a Ring-necked Pheasant and two Red-legged Partridges!

Now, I am under no illusion that both of these species just happened to get blown into this part of the state from a freak storm in Spain. However, both birds were outside of property lines, appeared to be of breeding age, fully flighted, and healthy individuals. My best guess about how these birds became established is through escapees from farms that raise these game birds for hunts. Thankfully, a few of these escaped their fate, and we were able to start our trip with them.

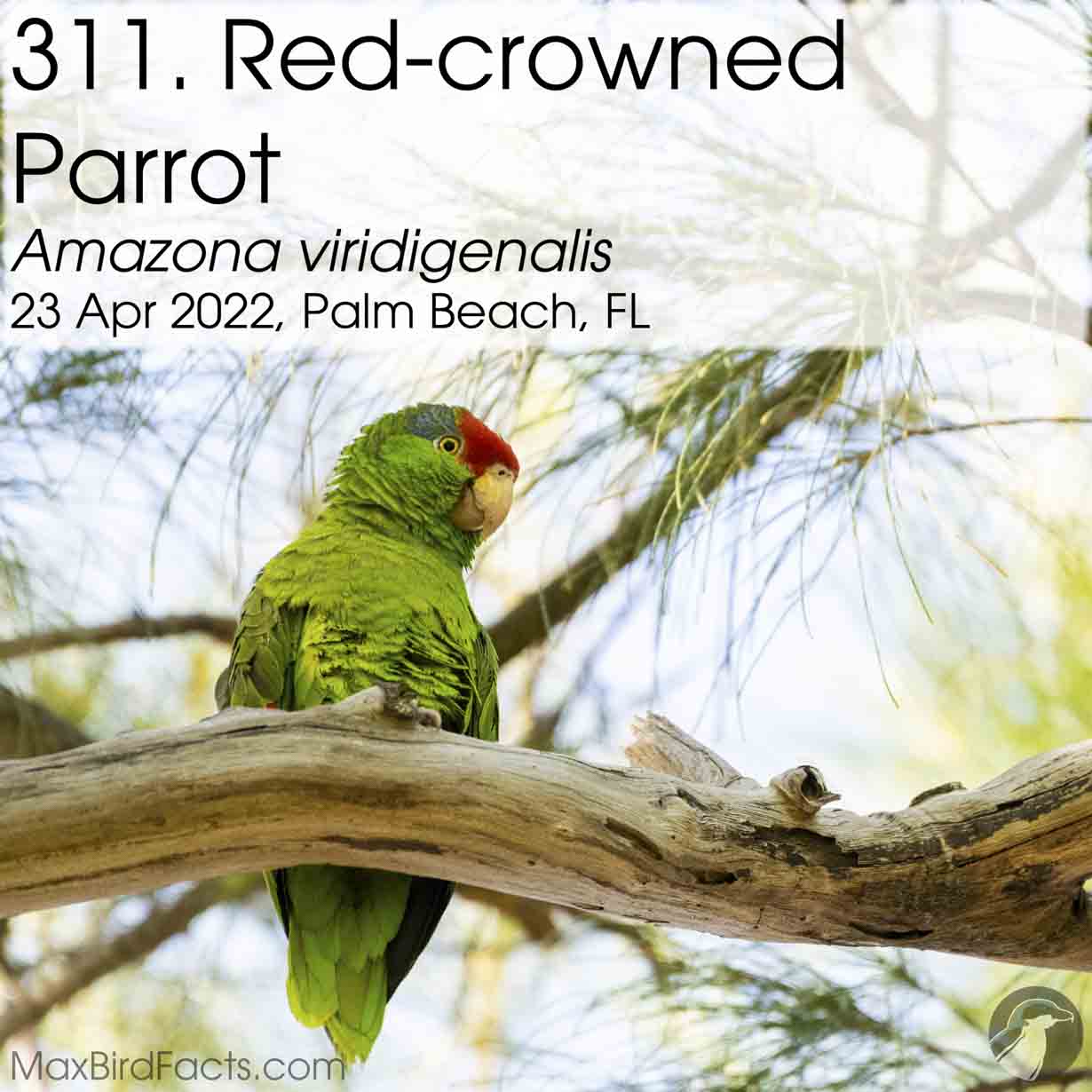

311. Red-crowned Parrot (Amazona viridigenalis). 23 April 2022. Palm Beach, Florida, United States.

The Red-crowned Parrot, or Amazon, was a species I was really hoping for from our South Florida Birding Bonanza. This critically endangered bird is more common in cities throughout the United States than they are in its native range in northern Mexico. Much like the other species on our target list, this bird had been spotted on and off on a golf course, so I saved it for our list of places to hit. Finding a place to park was a bit of a pain, but it was all worth it when a flock of six parrots flew screaming over the course.

They flew over too fast, and by the time I saw them, I only could see their tail feathers. But I knew if a group of this size flew around, more must be near. So, Kayla and I started walking down a grove of cedars when I heard a quiet, raspy murmur above us. Looking up, I saw a large green parrot with a red crown staring at us curiously. I don’t even want to think of how many images I initially took of this bird, but I was thrilled to have such a great look at this endangered species.

312. Blue-crowned Parakeet (Thectocercus acuticaudatus). 23 April 2022. Broward, Florida, United States.

The Blue-crowned Parakeet was on our radar but not a specific target during our South Florida Birding Bonanza. This seemed to be one of the most widespread parakeets on the south-central Atlantic coast of Florida, and this seemed to be the case. We had some great views of this little parrot on two occasions, but the second was much more special. Walking down a bridge looking for Amazons, three Blue-crowned Parakeets came screaming into the trees just above us. One curious little bird came down to near eye-level with us and sat and watched these strange hairless apes gawk at it. This parakeet was content to preen, scratch its head, and gnaw at its perch before flying back up to its companions. This was a complete surprise and chance encounter with this exotic species, and I’m so thankful for it.

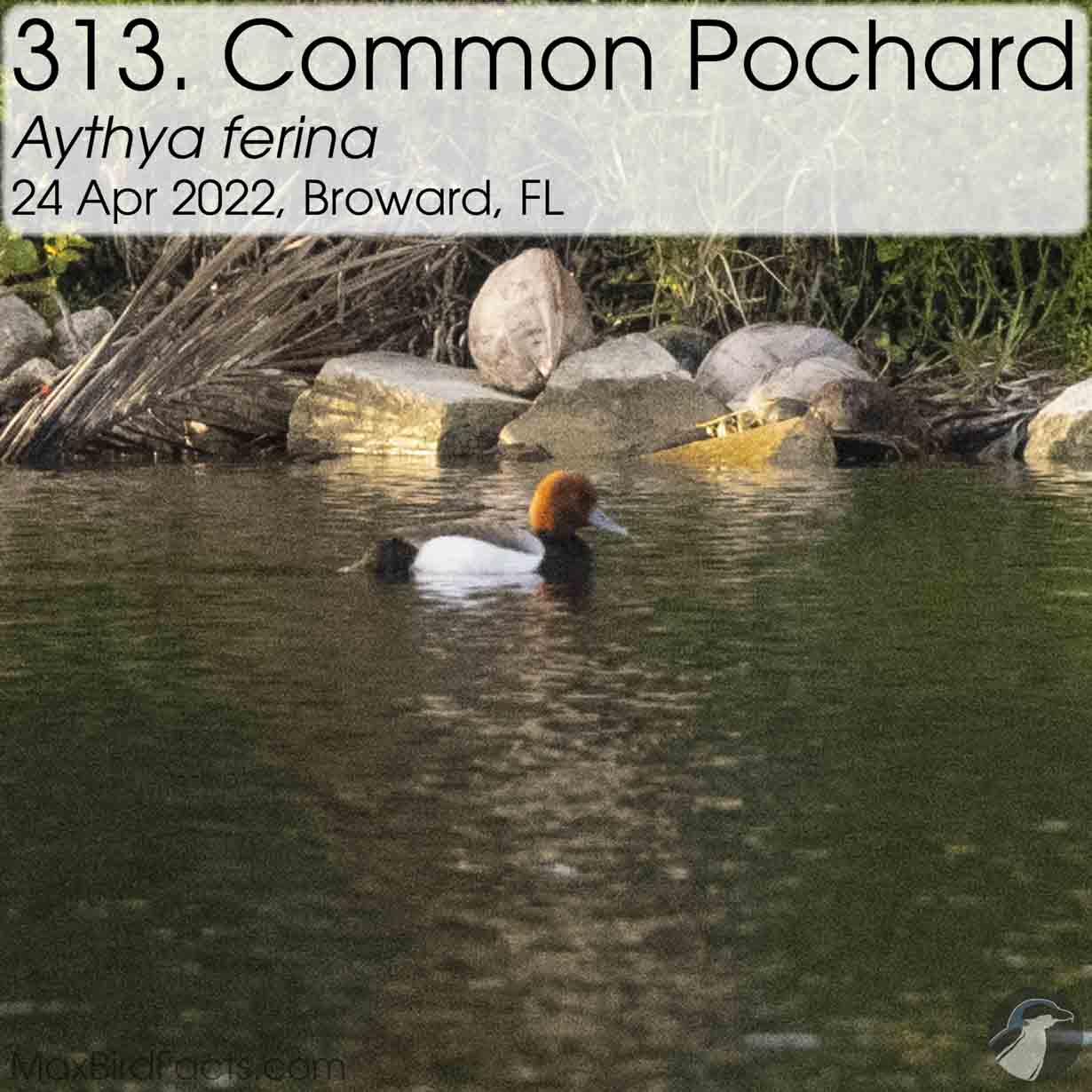

313. Common Pochard (Aythya ferina). 24 April 2022. Broward, Florida, United States.

Starting the morning of our second day of the South Florida Birding Bonanza, my girlfriend and I hit a pond where exotic duck species had been consistently reported. We had five targets and were lucky enough to list four of them. The first alien species we saw was the Common Pochard. This duck is native throughout Europe and parts of the Middle East and Asia. The most likely case for how this species, and the four other targets we were looking for, arrived in this little pond was someone stocked them. That said, these are breeding and fully-flighted individuals, so they count on eBird as escapees.

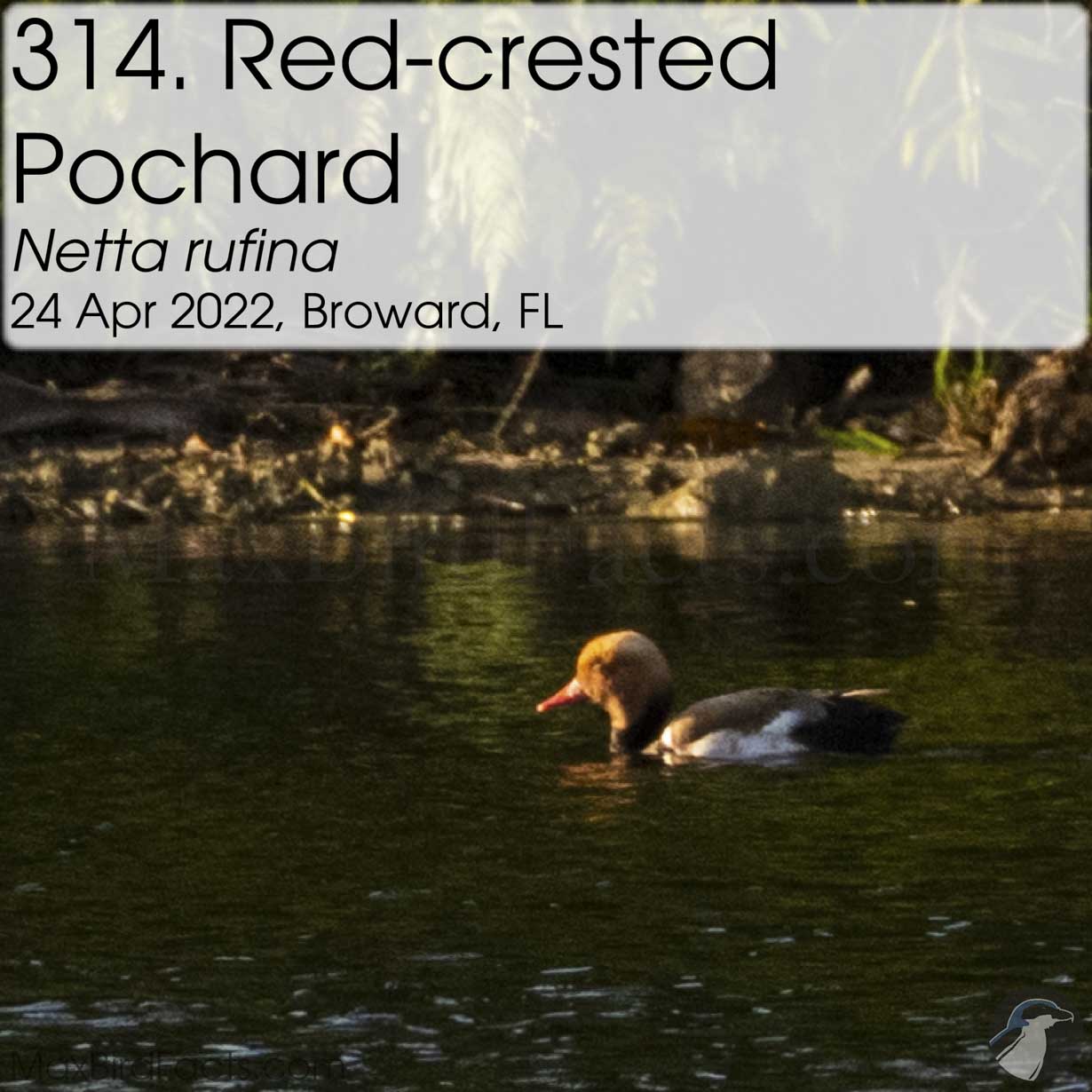

314. Red-crested Pochard (Netta rufina). 24 April 2022. Broward, Florida, United States.

The Red-crested Pochard was a much more vibrant relative to the Common Pochard, and this was the second exotic duck of the South Florida Birding Bonanza. This species is native to the same regions as the Common: Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. This male was much easier to spot and identify as well. Its beautiful orange head was similar to the Common, but its crimson bill was a striking feature.

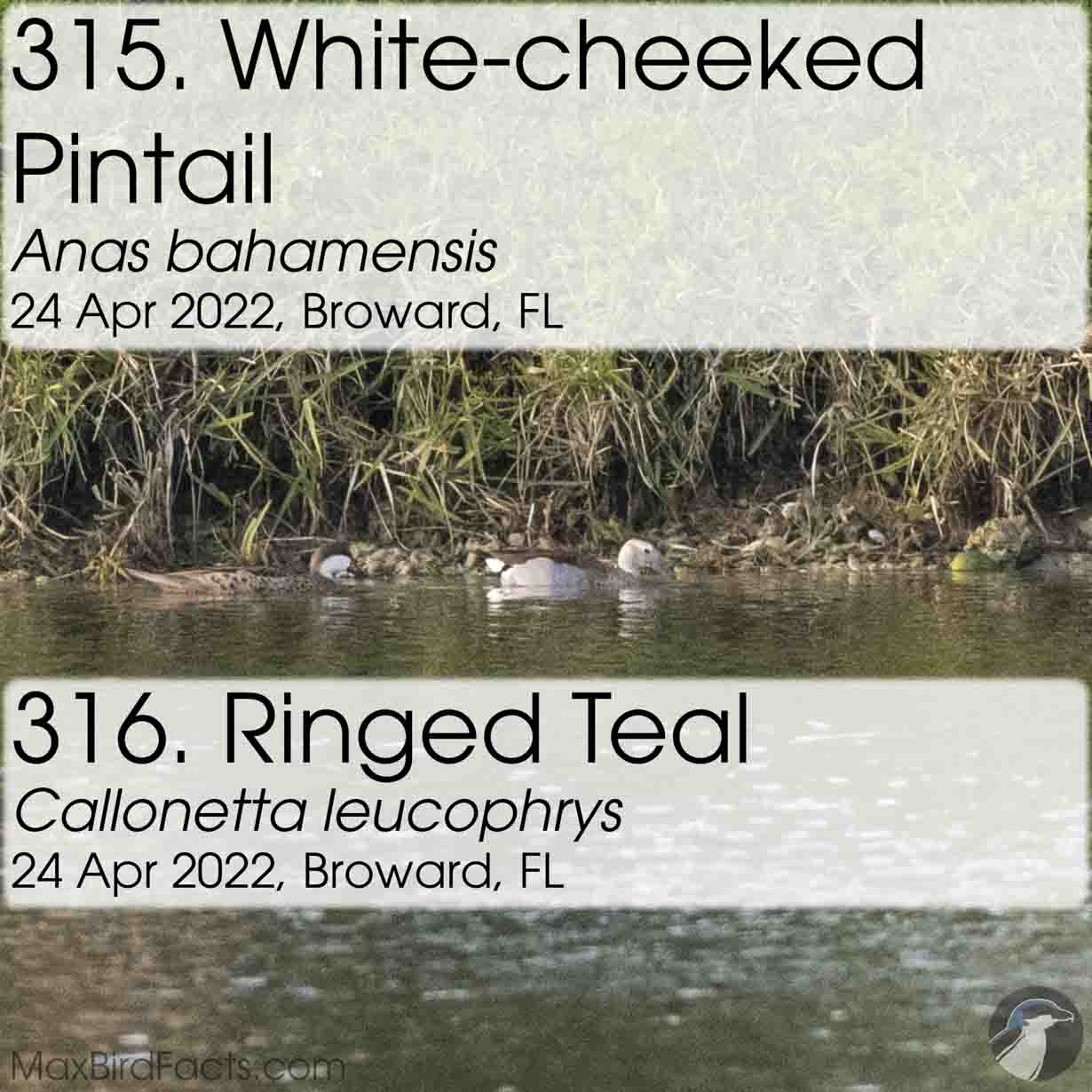

315. White-cheeked Pintail (Anas bahamensis). 24 April 2022. Broward, Florida, United States.

316. Ringed Teal (Callonetta leucophrys). 24 April 2022. Broward, Florida, United States.

These were the two exotic ducks I was hoping to see most of all during the South Florida Birding Bonanza: the White-cheeked Pintail and the Ringed Teal. The White-cheeked Pintail is native to the Caribbean and across coastal Central and South America, whereas the Ringed Teal is found in central and southern South America. These tropical ducks seemed to stick close together; I’m not sure if it is because they knew they were from the same region and bonded over that or if it was pure coincidence. Either way, it was a spectacular way to round out the morning.

317. Gray Kingbird (Tyrannus dominicensis). 24 April 2022. Broward, Florida, United States.

When I first saw the Gray Kingbird, I was photographing Monk Parakeets in a shopping mall parking lot. The kingbird flew into a tree not far from the parakeets, and my first thought was a Loggerhead Shrike, but its flight pattern was completely different. Creeping up to get a better look, I was surprised by the long conical bill staring back at me. This beautiful bird stayed perched for a few minutes, studying me, then took flight and slowly passed directly overhead and landed on the top of a tree at the edge of the lot. Once there, its mate flew in, harassed it, and stole its perch. The second kingbird called down to its mate from the perch, but I’m not sure what this display was.

A few hours later, we were looking for another target of the South Florida Birding Bonanza, and two more Gray Kingbirds flew into the top of a tree not more than fifty feet away. One bird made a rapid call, took flight, and landed promptly with a large dragonfly in its jaws. After the bird gobbled its meal, the pair stared at us curiously. Like all the other flycatchers from this year, I still am surprised by the seeming curiosity and intelligence these birds give off. They may not be as well studied for their intellect as corvids and parrots, but I would be willing to bet they are up there on the scale of clever birds.

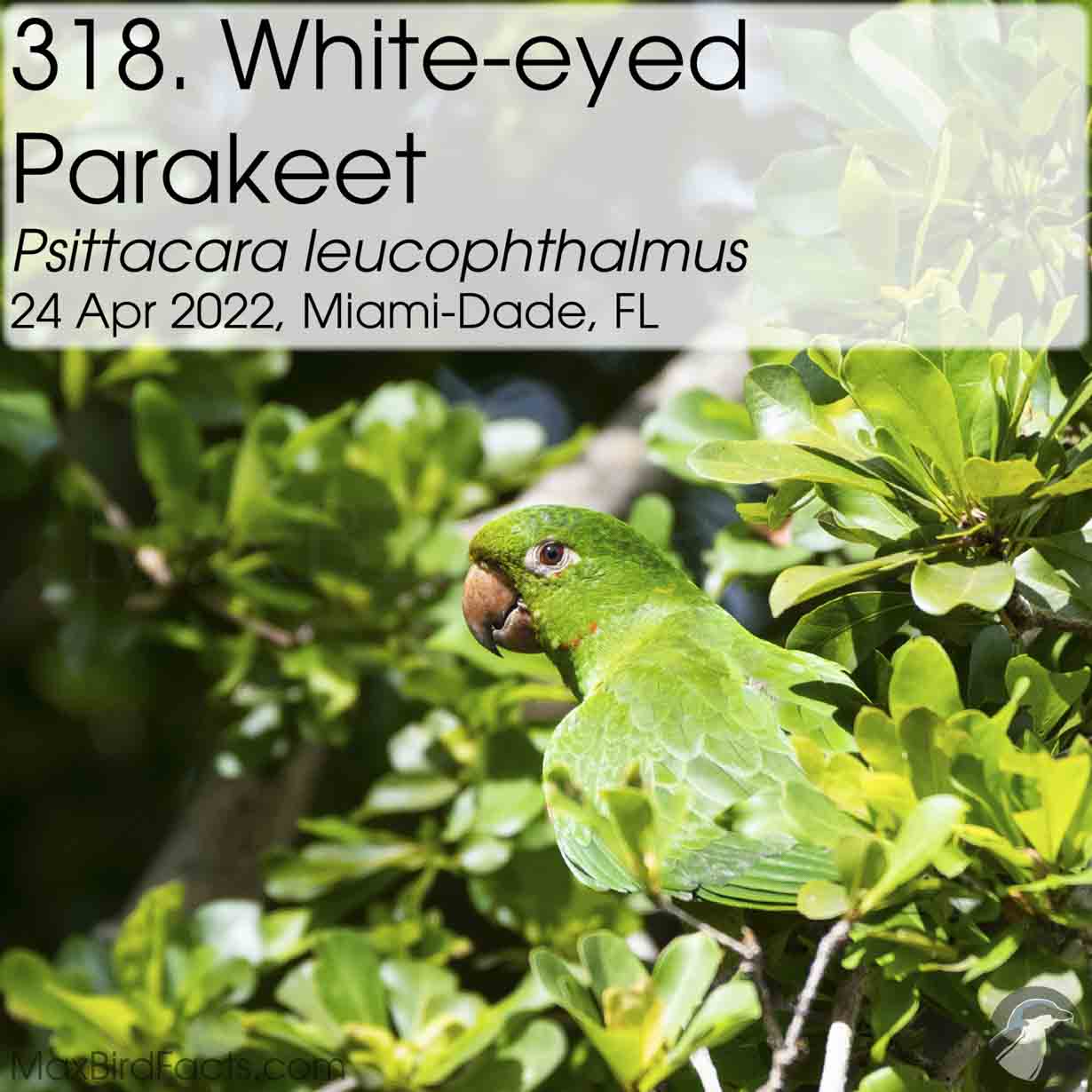

318. White-eyed Parakeet (Psittacara leucophthalmus). 24 April 2022. Miami-Dade, Florida, United States.

For some reason, the only parrot during the South Florida Birding Bonanza that triggered the rare bird alert was the White-eyed Parakeet. This small parrot is native throughout South America and is most likely here due to the illegal pet trade. Even though this bird was the “rarest,” we had very conservative counts of one flock of six and another of five, but these could easily have five more birds added.

There is some contention if this, and two other parakeet species are separate species. However, all these birds share nearly identical measurements, the same green aspect, flecks of red randomly throughout their body, and pale orbital skin. Yet, there is enough difference between the White-eyed, Mitred, and Red-masked Parakeets to consider each their own species. I won’t get into great detail about that here (hint for an upcoming article), but they are readily noticeable in the field.

319. Mitred Parakeet (Psittacara mitratus). 24 April 2022. Miami-Dade, Florida, United States.

The Mitred Parakeet proved much shier than their more boisterous White-eyed cousins. During the South Florida Birding Bonanza, we only saw one Mitred fly directly into the top of a tree, make a quiet call, and hunker down for a late morning nap. These birds are essentially a hybrid of features between the White-eyed and Red-masked Parakeets. They have much more solid red on the face and crown than the White-eyed, but the solid red rarely passes behind the eye, unlike the Red-masked. There are other markings to look for in adult birds, but I found this to be the most reliable.

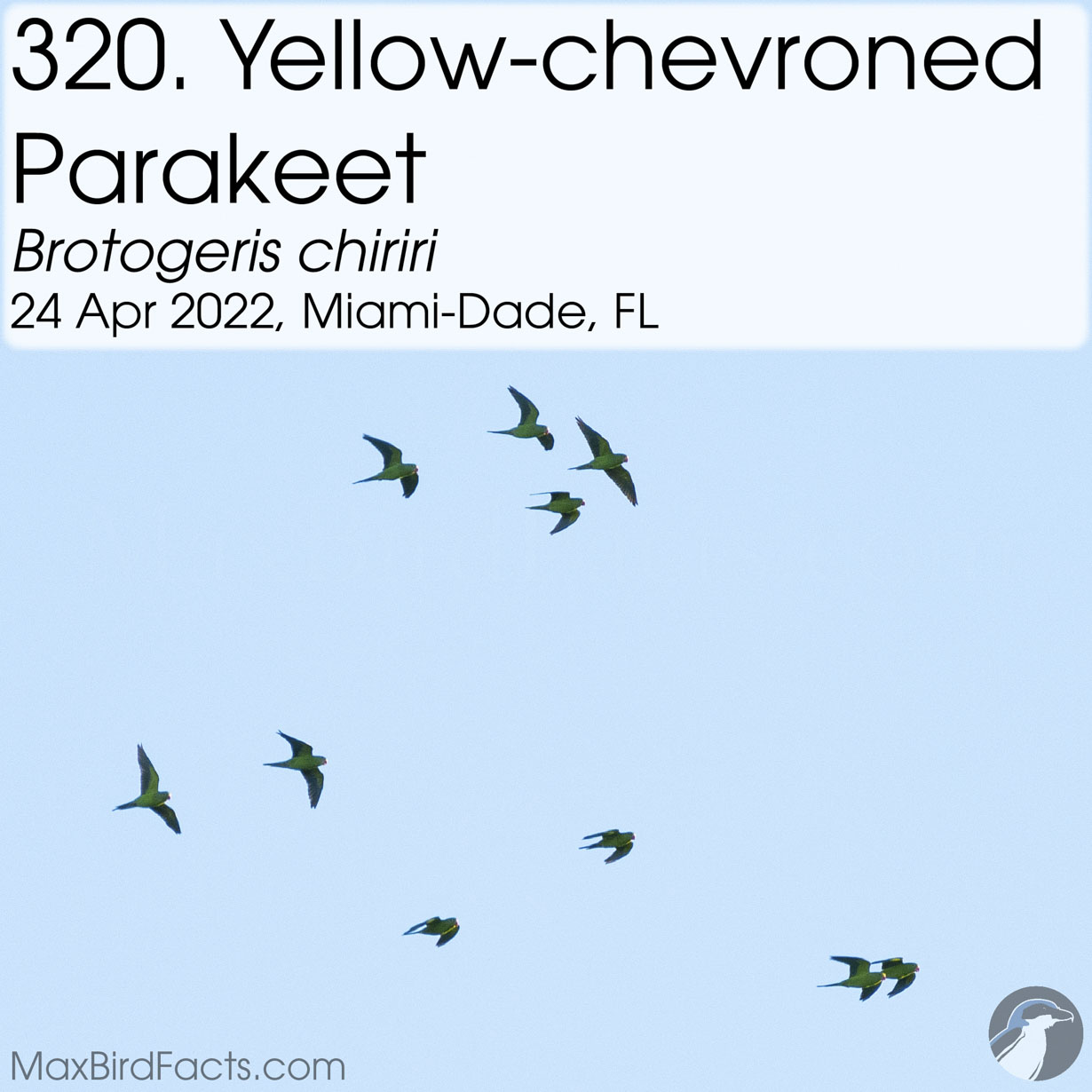

320. Yellow-chevroned Parakeet (Brotogeris chiriri). 24 April 2022. Miami-Dade, Florida, United States.

Yellow-chevroned Parakeets are the smallest parakeets from the South Florida Birding Bonanza, and like the Mitred, we only saw one. However, during the fall migration, my dad and I went through south Florida again, and we had much better luck with the Yellow-chevroned. Standing on the top of a hill, waiting for the sun to rise more, we heard the flight calls of a group of parrots. A few moments later, a small flock cleared the trees and was shooting past. We took a couple of images and saw the distinct yellow markings on the wings, compact pink bills, and blue flight feathers.

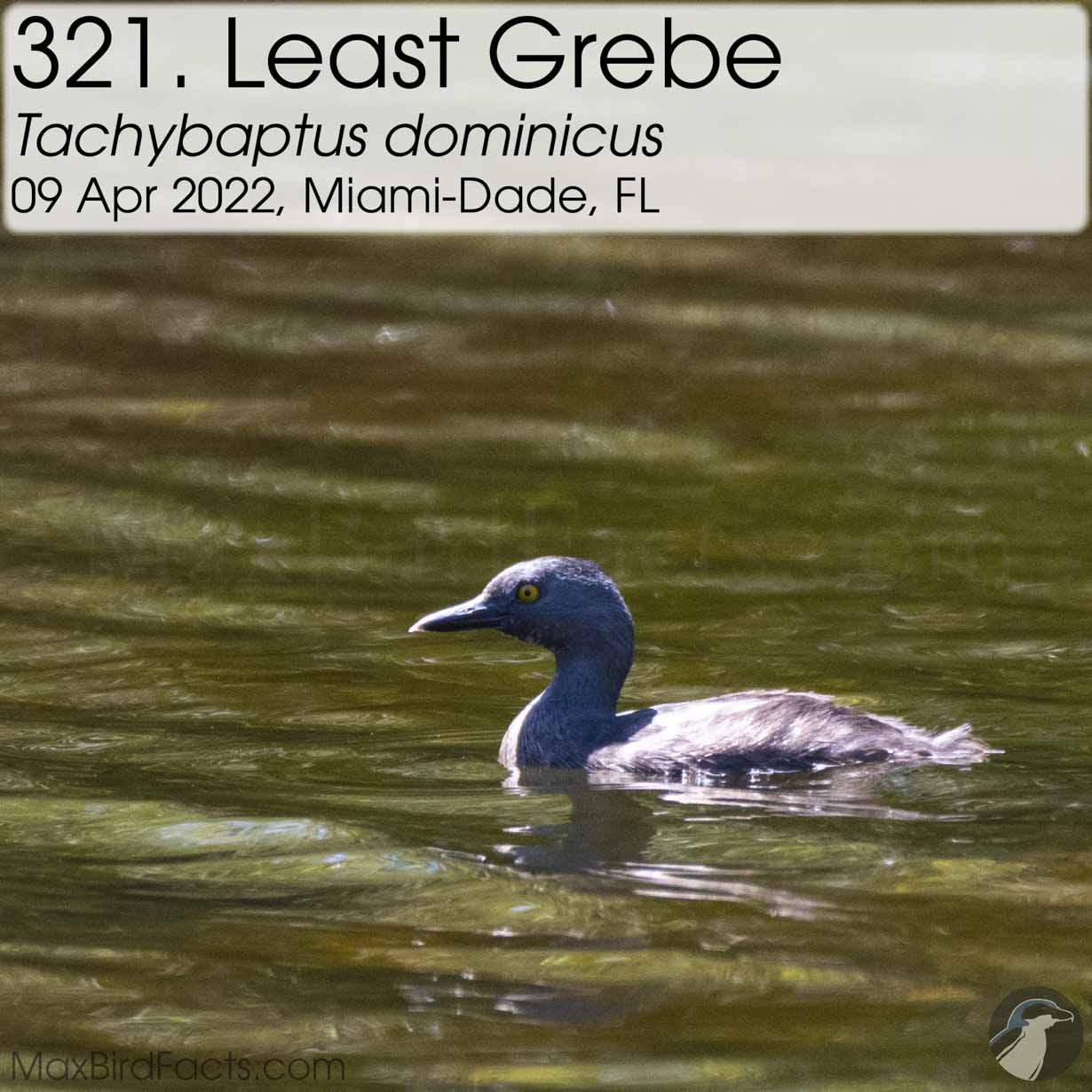

321. Least Grebe (Tachybaptus dominicus). 24 April 2022. Miami-Dade, Florida, United States.

The Least Grebe was a primary target for the South Florida Birding Bonanza. This rare bird had been consistently spotted for weeks leading up to our trip, and I was able to find a few lists of the exact coordinates. Arriving at the park, we made a beeline towards the pond and immediately saw another birder’s camera trained on the water. This South American grebe was content swimming around in the shallow water and allowed us to watch it for several minutes diving and chasing down fish. Thankfully, this bird seems to be a reasonably regular spring vagrant to Miami, and hopefully, I can see it again next season.

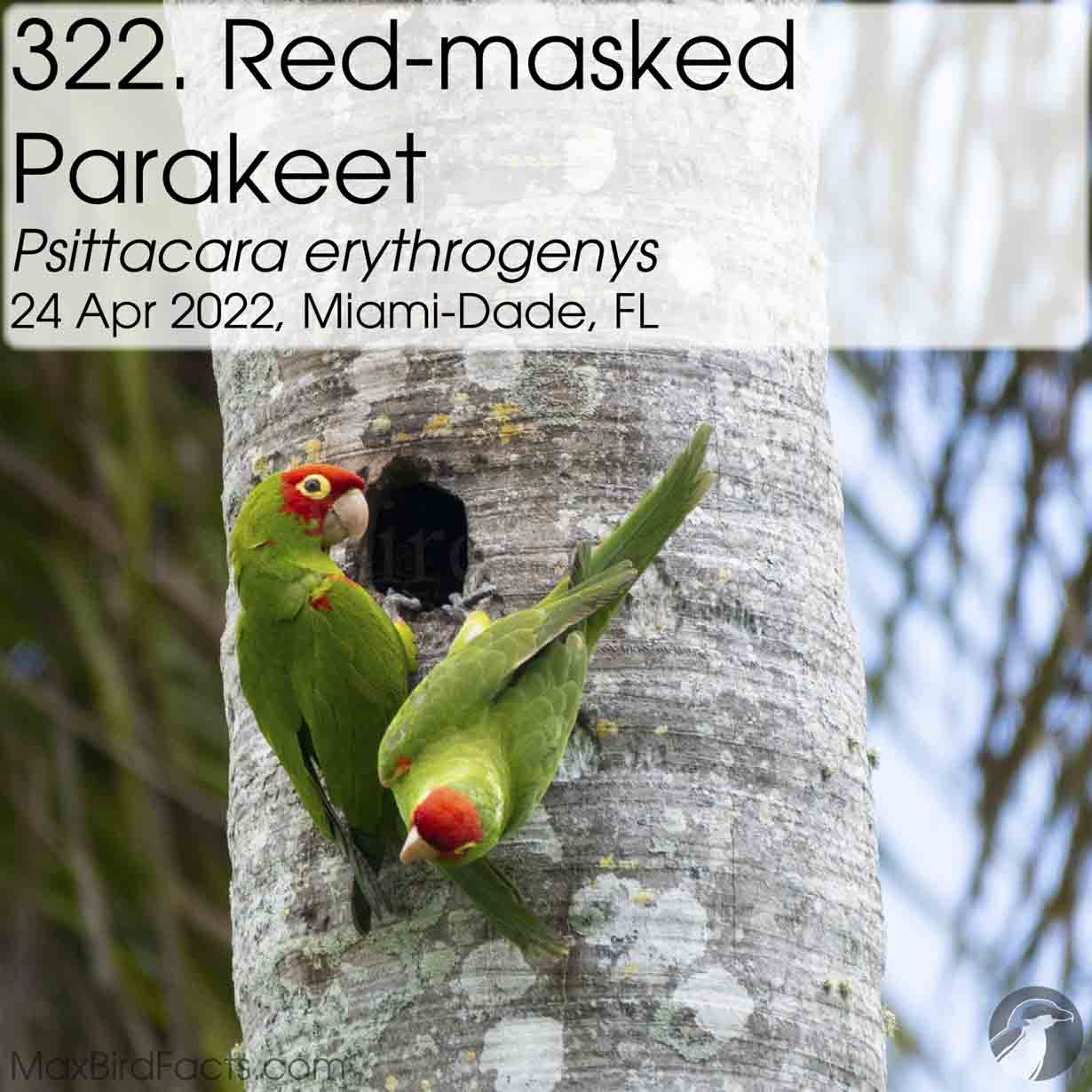

322. Red-masked Parakeet (Psittacara erythrogenys). 24 April 2022. Miami-Dade, Florida, United States.

These Red-masked Parakeets were a huge treat to see. Stalking the lists before making my plans for the South Florida Birding Bonanza, I found a park with the potential for four nesting lifers. Keeping this in mind, I kept checking the lists from this area, but the reports of these lifers started to fade away. Nevertheless, I kept this park on our list of places to hit, and I’m so happy I did.

Walking into the park, I immediately saw a grove of palm trees with gaping woodpecker holes and knew this was the area. Stepping into the shade, Kayla and I scrutinized each nest hole until we saw two heads resting on the edge of one with their eyes drowsily half closed. These parakeets seemed very content until a group of loud, unobservant tourists trudged through the grass directly below the tree. Both birds sprang out of the hole, one parakeet perched facing down, screaming at the oblivious family below, while the other scanned above for raptors. Once the family scurried off, the probably parents resumed their afternoon siesta.

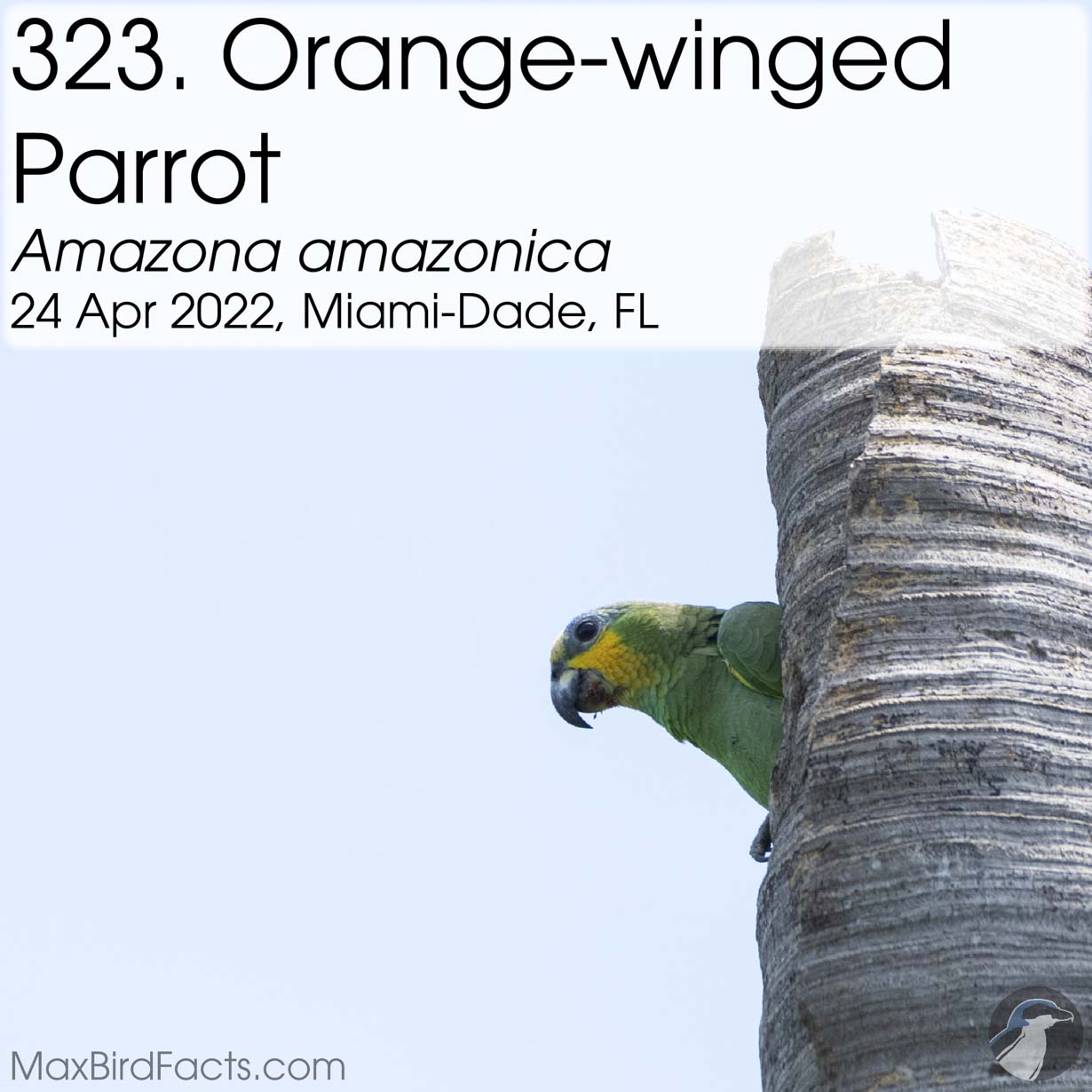

323. Orange-winged Parrot (Amazona amazonica). 24 April 2022. Miami-Dade, Florida, United States.

The Orange-winged Parrot was the second target for our nesting birds during the South Florida Birding Bonanza. Initially, we only saw one Amazon perched on the hollow top of a palm tree. However, a second bird flew in and traded places with the first. This was a clear indicator of incubation, each parent changing shifts so the other could find something to eat. This behavior was incredible to see, especially for an exotic parrot like this. These two didn’t seem nearly as perturbed by the noisy family as the Red-masked Parakeets. Both stayed vigilant yet quiet as they walked past. It was fascinating to see the differences between these two cousins’ behaviors to the same stimulus.

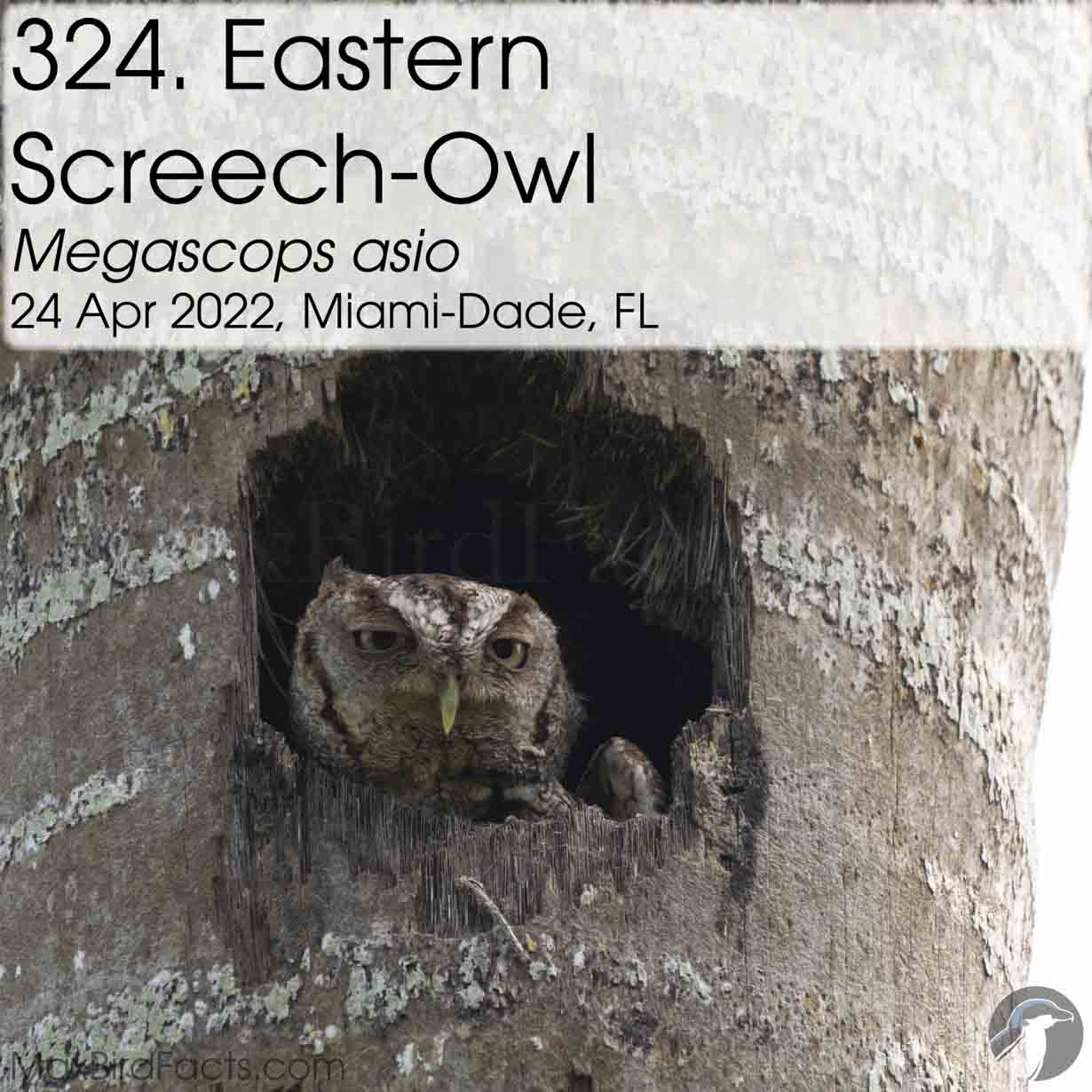

324. Eastern Screech-Owl (Megascops asio). 24 April 2022. Miami-Dade, Florida, United States.

The Eastern Screech-Owl was the third and last nesting bird of the South Florida Birding Bonanza. Unfortunately, we didn’t get our fourth target, but with the luck we were granted so far, it was hard to be disappointed. Kayla spotted this little owl before I could, and it blended in perfectly with the bark of its nest tree. It was odd seeing this ravenous bird hunter nesting only a few trees away from the nesting parrots and a Red-bellied Woodpecker pair, but all the neighbors seemed to get along just fine. The owl only lifted its head a handful of times and lazily opened its eyes to look at us before resting its chin on the edge of the nest opening. We left it alone and focused on the parrots so the owl could rest before its night shift in a few hours.

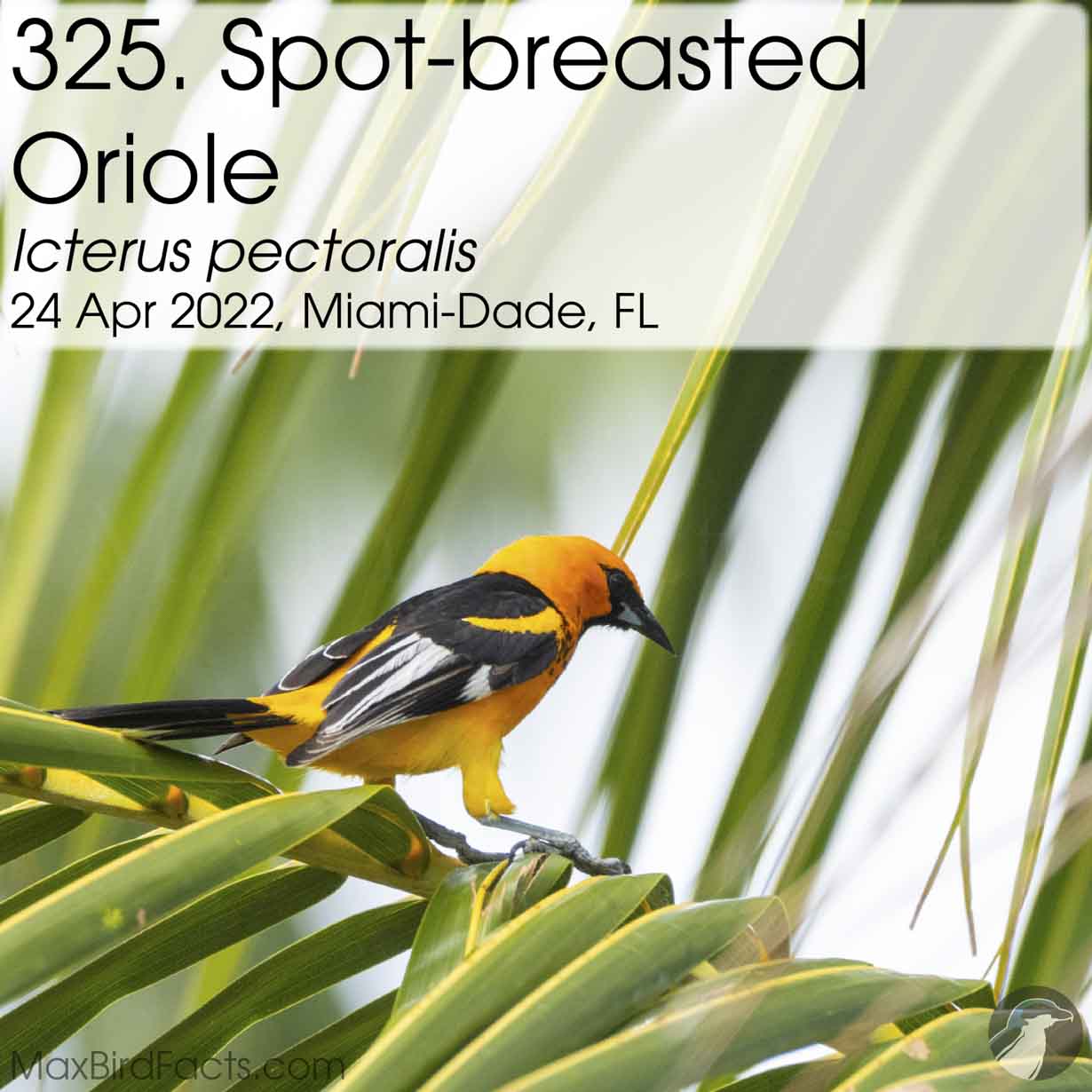

325. Spot-breasted Oriole (Icterus pectoralis). 24 April 2022. Miami-Dade, Florida, United States.

The Spot-breasted Oriole was a spectacular find by Kayla! This species was a peripheral target that was reported all over the Miami area, but it proved just as elusive as its northern cousins. We stopped in a residential area to stalk some feeders for potential targets when Kayla said she saw something orange fly into a palm tree in front of us. Looking through the fronds, a gorgeous adult Oriole pops up into the open. These birds are originally native to southern Mexico and Central America, but the climate and habitat in South Florida are more than adequate for them. A stellar surprise and amazing addition to our trip!

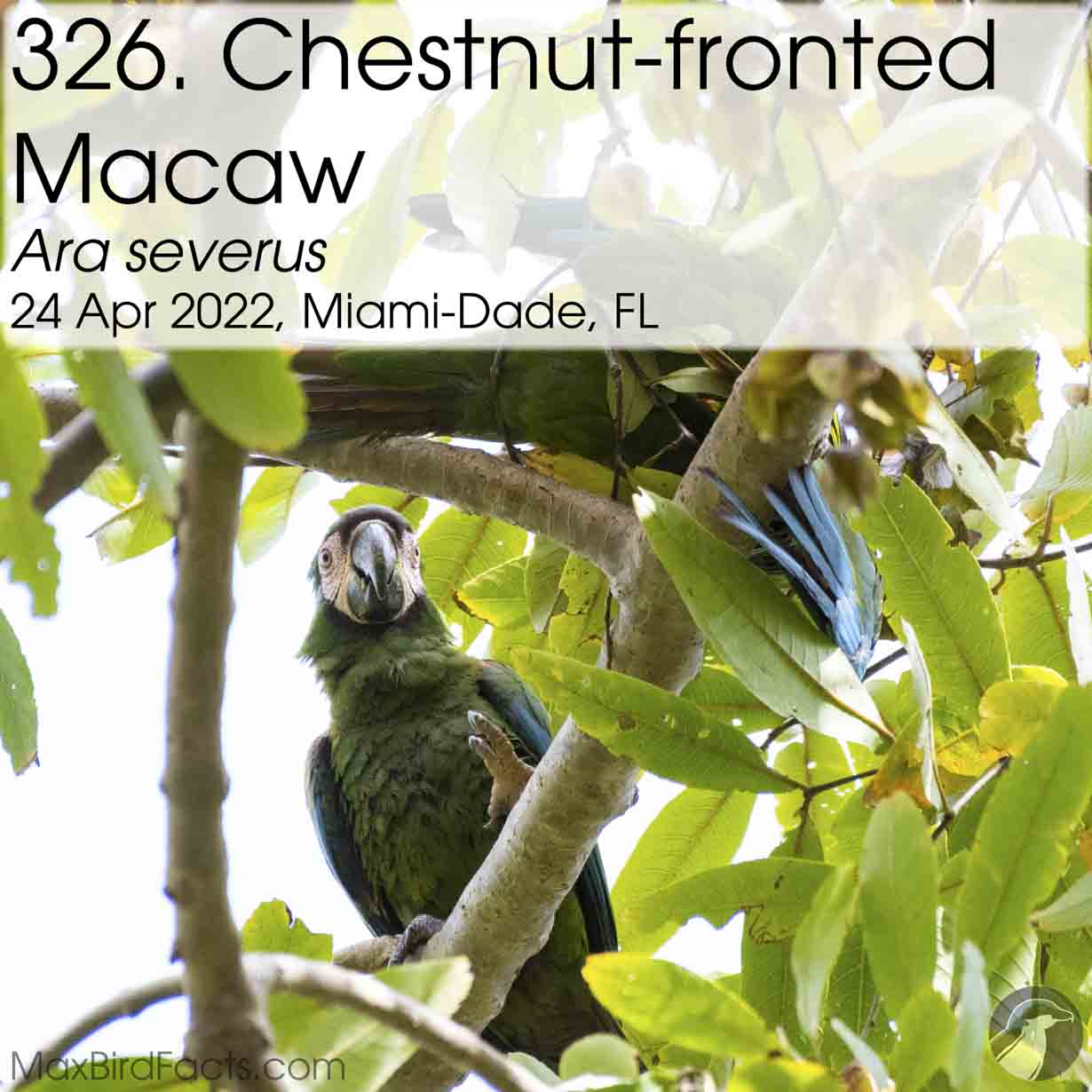

326. Chestnut-fronted Macaw (Ara severus). 24 April 2022. Miami-Dade, Florida, United States.

The Chestnut-fronted Macaw was the largest and hardest-to-find parrot of the South Florida Birding Bonanza. This was another species that had been reported on and off all around Miami, and I figured its size would make them somewhat easy to locate. I couldn’t have been more wrong.

On our final stop in Miami, we spent almost half an hour looking in trees, playing calls, and hunting for these macaws, but we weren’t getting any results. I felt defeated when we walked back to the car, but I thought I heard a parrot call from the trees on the other end of the parking lot. It sounded deeper and raspier than all the parakeets and Amazons we had seen previously, and I sprinted for the trees. Scanning each limb, I finally found two massive macaws way up on the top of a tree, playing with each other. One bird would lunge at the other, then fall and hang upside down from the branch taunting the other bird, and seeing this playful behavior made the wait well worth it for our last parrot of the trip.

327. Cape May Warbler (Setophaga tigrina). 24 April 2022. Miami-Dade, Florida, United States.

The Cape May Warbler was the last lifer of the South Florida Birding Bonanza. The spot I had picked to end our trip was just on the edge of Everglades National Park, and there was massive potential. Sadly, whether it was the wrong time of day or some other factor, this location turned out to be a gigantic flop. However, with our luck leading up to the end, we had an incredibly successful trip. One hundred thirteen species total, 18 lifers for me, and 46 lifers for Kayla; I would say we had a stunning birding excursion into South Florida!

328. Merlin (Falco columbarius). 12 May 2022. Osceola County, Florida, United States.

The Merlin has been a nemesis of mine for a while. Every time I’ve thought I had this falcon in my camera, it turned out to be an American Kestral. However, I finally saw my first Merlin chasing down a flock of Cattle Egrets. It was distinctly larger, darker, and rapid continuous wing beats told me this was the falcon I’d been hunting for. Fast forward five months, my dad and I were in Miami on our way to see the Florida Keys Hawk Watch, and a Merlin flew low and fast over a group of pigeons. It perched on the top of a bare tree, and we were able to get incredibly close to her and take some fantastic shots.

Our luck with these raptors continued further down the state, where we watched one fly out from Fort Zachary Taylor over the Atlantic Ocean towards Cuba for the winter. Of course, we knew about the migration over the sea, but watching a falcon fly directly over the ocean and disappear into the horizon was a sight I don’t quite know how to describe. I hope that bird made it to its destination and is snacking on some birds down there.

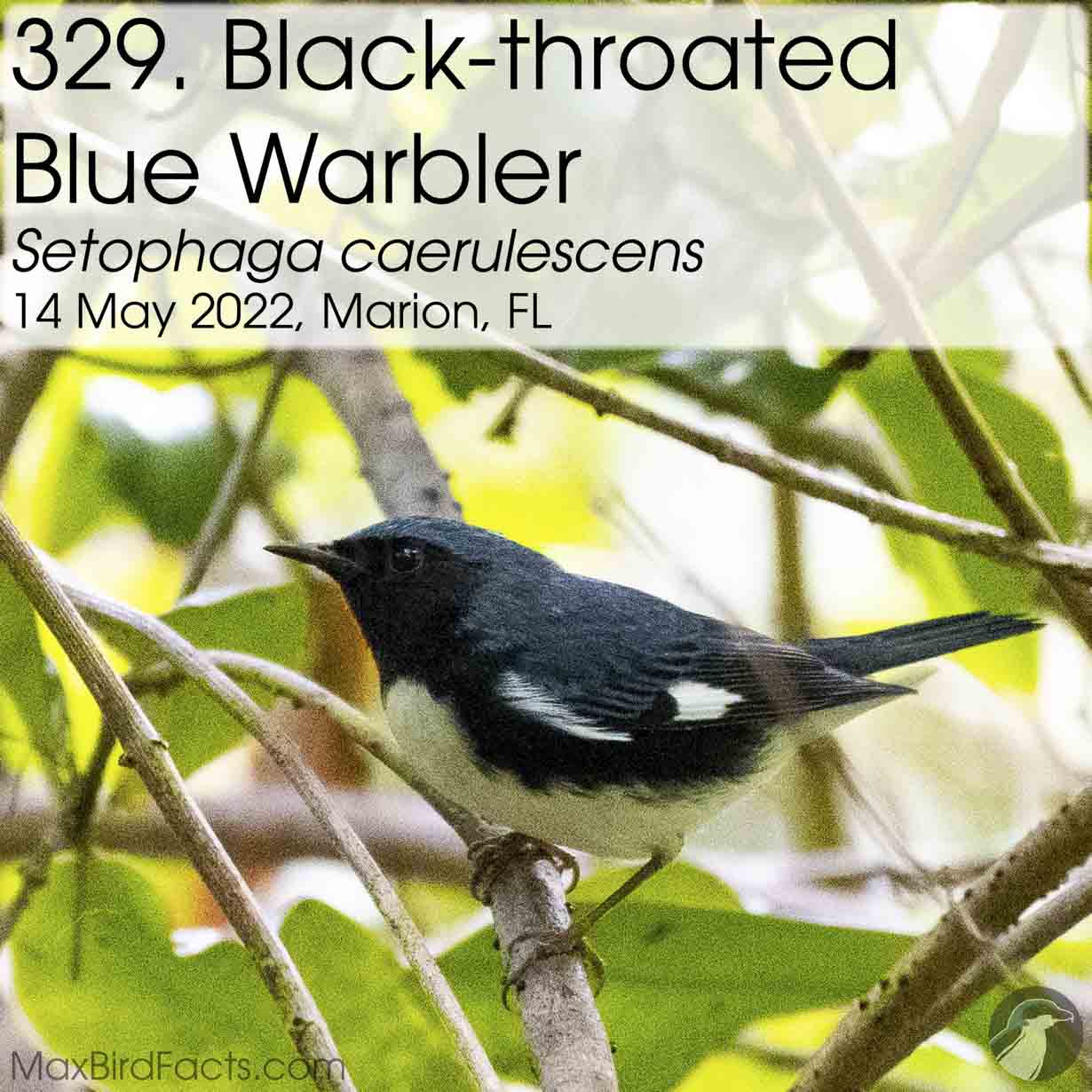

329. Black-throated Blue Warbler (Setophaga caerulescens). 14 May 2022. Marion County, Florida, United States.

It’s always great getting a lifer on the Big Day. I got my first Black-throated Blue Warbler during the May 2022 Big Day. This beautiful and elusive warbler was really tricky to photograph but well worth the effort. It seemed to like staying on the heavily vegetated limbs of the oak, poking and prying its narrow beak into the bark and pulling out insects.

During our trip to the Keys, we stopped at Fort Zachary Taylor, and my God, there were dozens of BTBW fluttering around in the trees! This stop proved a massive score for us during our October South Florida trip, but more of that to come. The only explanation we could come up with was that these birds had one final refueling before jumping over the Atlantic into Cuba.

330. Bobolink (Dolichonyx oryzivorus). 14 May 2022. Marion County, Florida, United States.

The Bobolink was another lifer on the Big Day, but it is still a bird I need better photos of. These grassland breeders funnel through Florida on their seasonal migrations going as far south as Argentina in the winter and north to Hudson Bay in the summer. Photographing two females a few hundred yards in a sod farm in the spring proved challenging. Not only were they small enough to hide being a patch of dirt or grass, the heat mirage heavily distorted our views of these birds. Thankfully, I got good enough focus on a couple of images to get a confirmed identification on the back and head markings.

331. Field Sparrow (Spizella pusilla). 30 June 2022. Union County, Illinois, United States.

Like many sparrows, my first encounter with a Field Sparrow was via song only. Driving through southern Illinois, I thought I heard a song I didn’t immediately recognize, so my dad pulled over. I got out of the car, grabbed my camera, and started to scan for the bird when I felt something crawling on my ankle. I looked down and saw half a dozen of the biggest ticks I had ever seen crawling up my jeans. I took out my Leatherman and started to pick them off my clothes before they could embed their heads into my skin. I’ve dealt with ticks in the past, but never ones this voracious; they must have been starving from a long winter.

A few days later, I picked up the same call in central Illinois, and low and behold, more ticks on my jeans. This time the sparrow popped up for a few moments and allowed us to get some photos. I think there is a correlation between the abundance of ticks and where the Field Sparrows tend to forage. Ticks would make an excellent food source for a young chick. The invertebrate is rich in protein, and if the parent can find one gorged in blood, it is all the better for the developing hatchling. Definitely a skin-crawling annoyance at the time, but a fascinating experience to think back on.

332. Yellow Warbler (Setophaga petechia). 30 June 2022. Jackson County, Illinois, United States.

Bright streaks of gold shot back and forth on a path my dad and I were walking. After a few seconds of pishing, a dazzling male Yellow Warbler came rocketing out of the willows to see what was going on. The attitude some of these warblers have is shocking to me. These tiny songbirds have a lot of spunk for a bird that weighs only a few grams. Unlike other warblers with yellow markings and plumage, Yellow Warblers are almost entirely yellow. Males are distinguished by their fine orange-streaked breasts. Since my initial viewing, I’ve seen this vibrant species several times. I even stumbled upon what I think was a nesting site of 14 individuals.

333. Kentucky Warbler (Geothlypis formosa). 30 June 2022. Jackson County, Illinois, United States.

The Kentucky Warbler was a challenging bird to photograph. Staying in the wet undergrowth of southern Illinois, these warblers were very shy. However, looking into their genetics, I’m not too surprised by this behavior or their appearance. The genus Geothlypis, Greek for “ground warbler,” is shared with the Common Yellowthroat, which I have much experience within the Florida marshlands. The dark markings around the eyes seem to be as much shared as their preferred residence and reclusive nature. It was a fun challenge trying to photograph these vibrant shots in the dark.

334. Wood Thrush (Hylocichla mustelina). 30 June 2022. Jackson County, Illinois, United States.

The Wood Thrush taught me the reticence for which thrushes are so well-known. Even though I never saw one of these birds, their songs filled the summer forests throughout Illinois. Their fluty, ethereal calls were a spectacular soundtrack while walking through the woods looking for breeding warblers. I would love to see one of these hermits and make some beautiful photos. Hopefully, I can spend some time with one this spring on its way back up to its breeding grounds in the northeast.

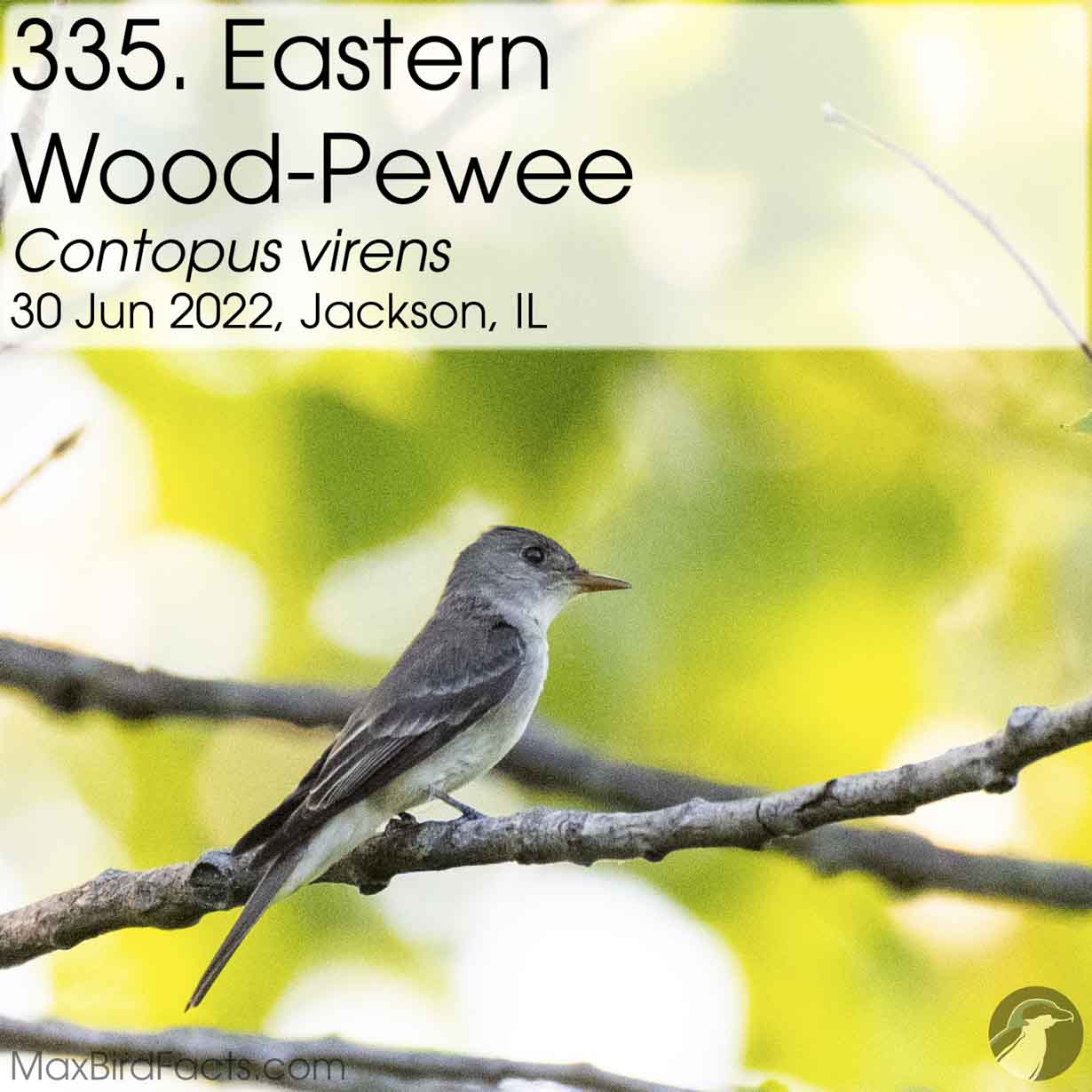

335. Eastern Wood-Pewee (Contopus virens). 30 June 2022. Jackson County, Illinois, United States.

The Eastern Wood-Pewee is a bird that has earned its name through the sound of its song. With a consistent cool gray head, neck, and back, darker wings with subtle wing bars and trim, dark maxilla, dull peach mandible, clean white throat, sooty vest, and a white streak down the center of the abdomen, Eastern Wood-Pewees give more than a few great field indicators when trying to identify them.

Eastern Wood-Pewees are the type specimen for their genus Contopus, Greek for “pole foot.” Still, their most striking way of identification is through their voice. Like many other avian species, the Pewees are onomatopoeically named. Their notorious song “PEEawee peeyoooo” was a beautiful sound to hear and understand for the first time in the southern Illinois summer while looking for warblers, and even more delightful when listening to them in the early fall in Florida.

336. Yellow-billed Cuckoo (Coccyzus americanus). 30 June 2022. Jackson County, Illinois, United States.

The Yellow-billed Cuckoo was another bird by ear this year. These secretive brood parasites can perch motionless like a gargoyle among the leaves, making them nearly impossible to spot. When I first heard this cuckoo’s call, I immediately thought it was a King Rail mixed with a Red-bellied Woodpecker. The call starts as a rapid series of ka-ka-ka-ka-ka, then slows to kow-kow-kow-kow, and ends with a few klow notes. It was, and still is, a very odd call to hear, but it fits such an odd bird.

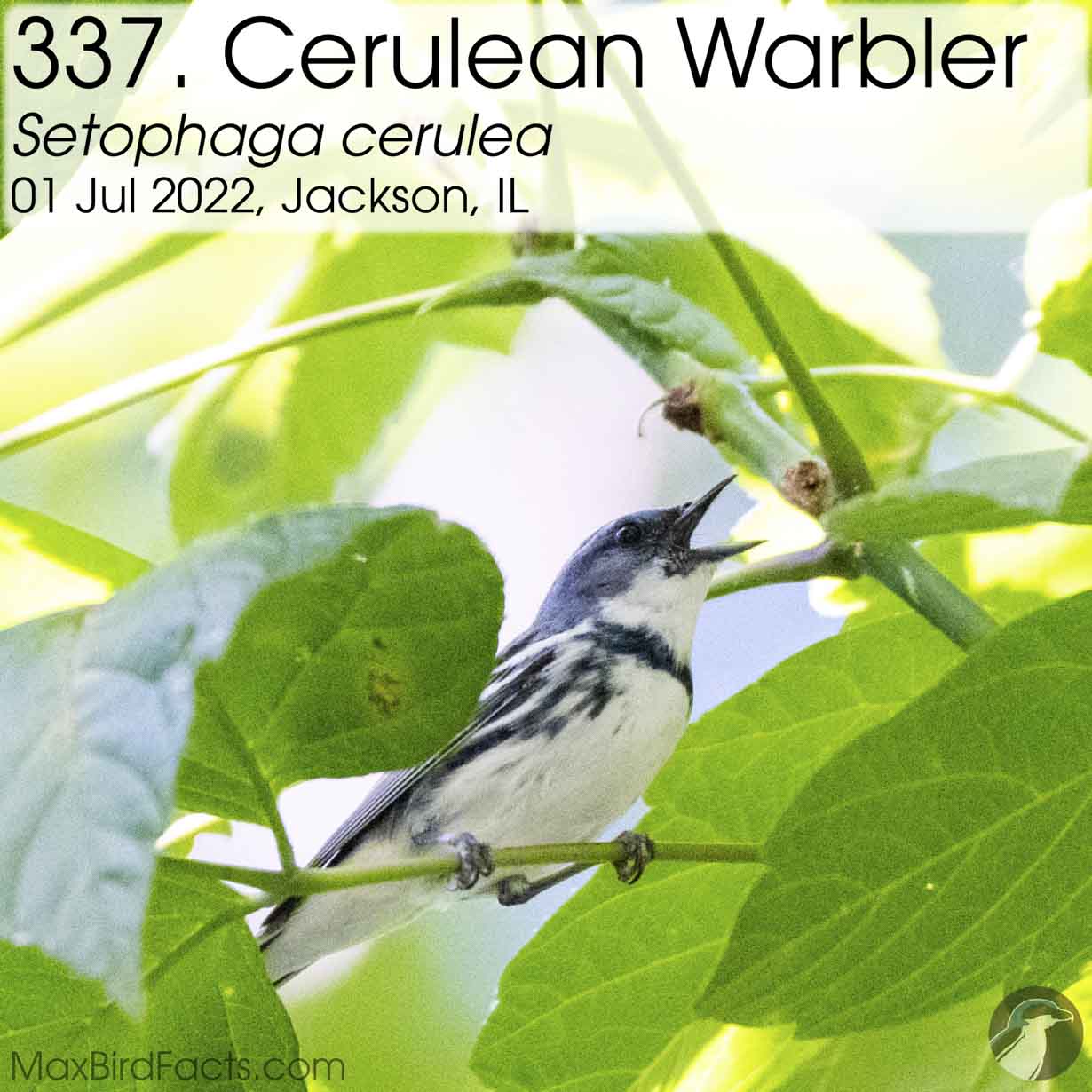

337. Cerulean Warbler (Setophaga cerulea). 01 July 2022. Jackson County, Illinois, United States.

The Cerulean Warbler was a primary target in Southern Illinois, and thankfully we had a fantastic encounter with two beautiful males. These birds are scarce in Florida, but Scott pointed us to an area where nesting Ceruleans were almost guaranteed. With this information, my dad and I hit the location in the evening, just before sunset the first day, with no luck. The following day we arrived before sunrise for the dawn chorus, and our target birds greeted us. They were cautious of us but curious enough from our pishing to come in close for some lovely photos.

338. Worm-eating Warbler (Helmitheros vermivorum). 01 July 2022. Jackson County, Illinois, United States.

Worm-eating Warblers were on our radar while looking for Cerulean Warblers this summer in southern Illinois, and we were lucky enough to stumble on one. Walking through the moist, dim morning, a small warbler shot across the path in front of us. I was able to get my binoculars up in time to see the sandy-buff face, needle-like pink bill, and black stripes through and above its eyes. By the time I had my binoculars down and camera up, it had flown at least a hundred yards into the woods. We picked up a few calls from possibly a second Worm-eating Warbler farther down the trail, but it could have been the original bird sticking close to watch us.

339. Orchard Oriole (Icterus spurius). 02 July 2022. Kankakee County, Illinois, United States.

The Orchard Oriole seems to fit the mold of the other orioles I’ve checked off my life list; you hear them first and will see them later. This bird caught me completely unprepared without my binoculars or camera. Walking around the backyard of my cousin’s grandparent’s property, I caught a call I knew was different. I ran Merlin, and the Orchard Oriole immediately popped up as the suspect. I replayed the call, and a little orange bullet shot out from the grass, landed in a tree above me, made a quick call, then shot out the back of the tree into dense brush.

340. Dickcissel (Spiza americana). 03 July 2022. Kankakee County, Illinois, United States.

The Dickcissel would have definitely been bullied in high school for its name. This grassland grosbeak is a nesting bird throughout the Midwest and winters in northern South America. This bird was a big target that was pretty common in Illinois, and this proved to be true. On nearly every outing where a large patch of grass was available, Dickcissels would appear. Even on the 4th of July, a Dickcissel was singing his heart out in my uncle’s backyard.

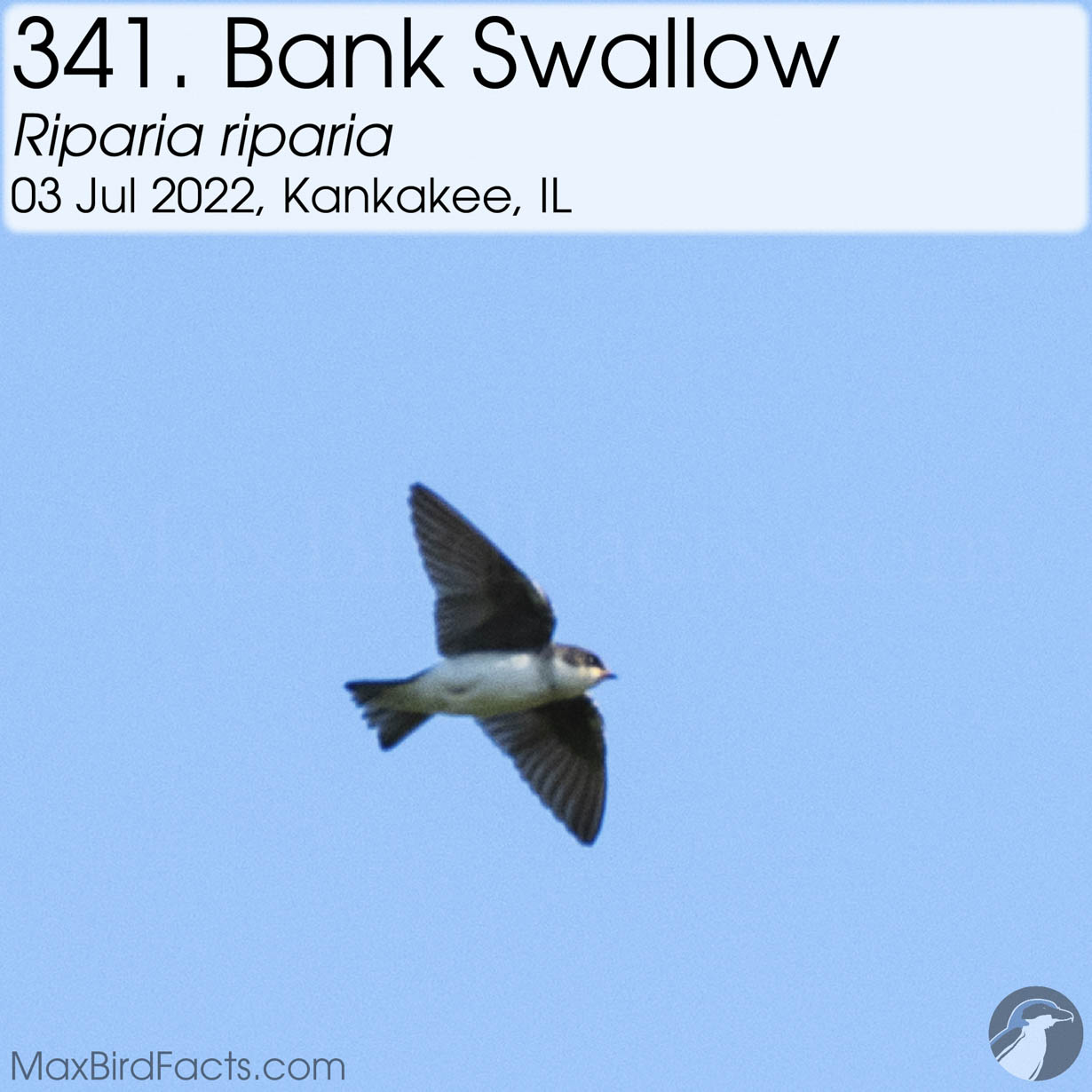

341. Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia). 03 July 2022. Kankakee County, Illinois, United States.

The Bank Swallow was a welcome surprise while trying to photograph a buzz of swallows this summer. Initially, I thought this was a young Tree Swallow, but the dark collar was way too pronounced for that. I’ve seen this species a handful of other times since then, but these elegant birds have been a considerable challenge to get clear images.

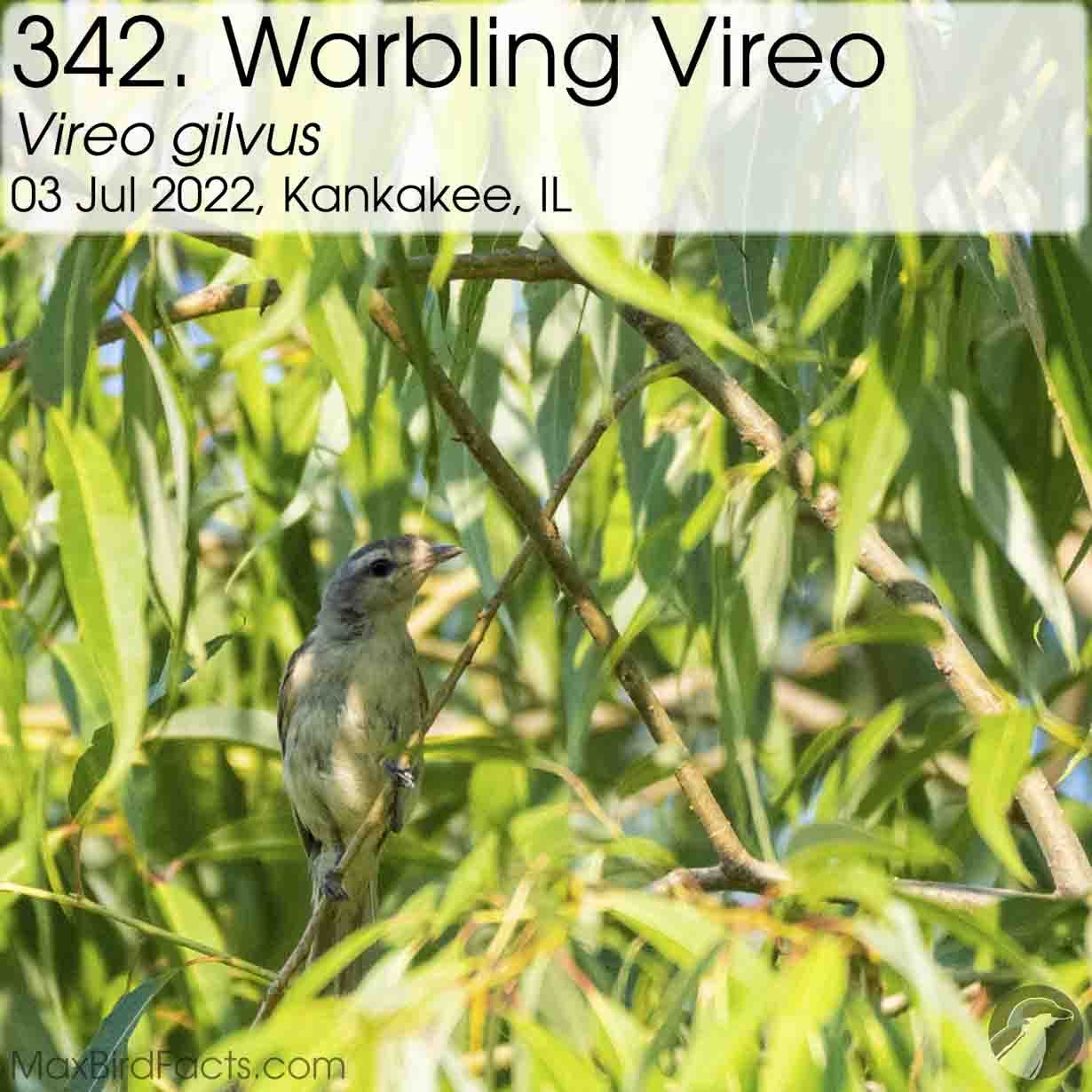

342. Warbling Vireo (Vireo gilvus). 03 July 2022. Kankakee County, Illinois, United States.

The Warbling Vireo was another Illinois specialty. The variety of birds I’ve gained from Illinois is surprising, especially since we share many migratory species here in Florida. The grasslands and vast agricultural fields throughout and surrounding Illinois probably account for this. The Warbling Vireo is a summer visitor to virtually the entire United States outside of the Southeast and winters down in Mexico.

Their gray crown, beady eyes, white throat and breast, and yellowish flanks are all defining features of this bird. However, the first thing that caught my eye about this bird was its typical reclusive behavior all Vireos share. I can easily understand how this bird could initially pass as a generic warbler, but this behavior and the characteristic broad Vireo bill make this bird stand out.

343. Neotropic Cormorant (Nannopterum brasilianum). 18 August 2022. Brevard County, Florida, United States.

The Neotropic Cormorant taught us to chase down rare vagrants as soon as they are reported. This super rare cousin to the more widespread Double-crested Cormorant typically spends their time in the Caribbean, Mexico, Central and South America, and southeastern Texas. This bird was listed a handful of times, so my dad and I made the drive to see it. We stood in the coordinates from another helpful birder’s list and started combing through cormorants for the vagrant. Not too long after, the Neotropic Cormorant flew in and landed on a post. Once the rare bird landed, we could clearly see the white V around its gular (patch of extendable throat skin), less orange flesh in front of the eye, and longer tail feathers that all pointed to this bird being our target.

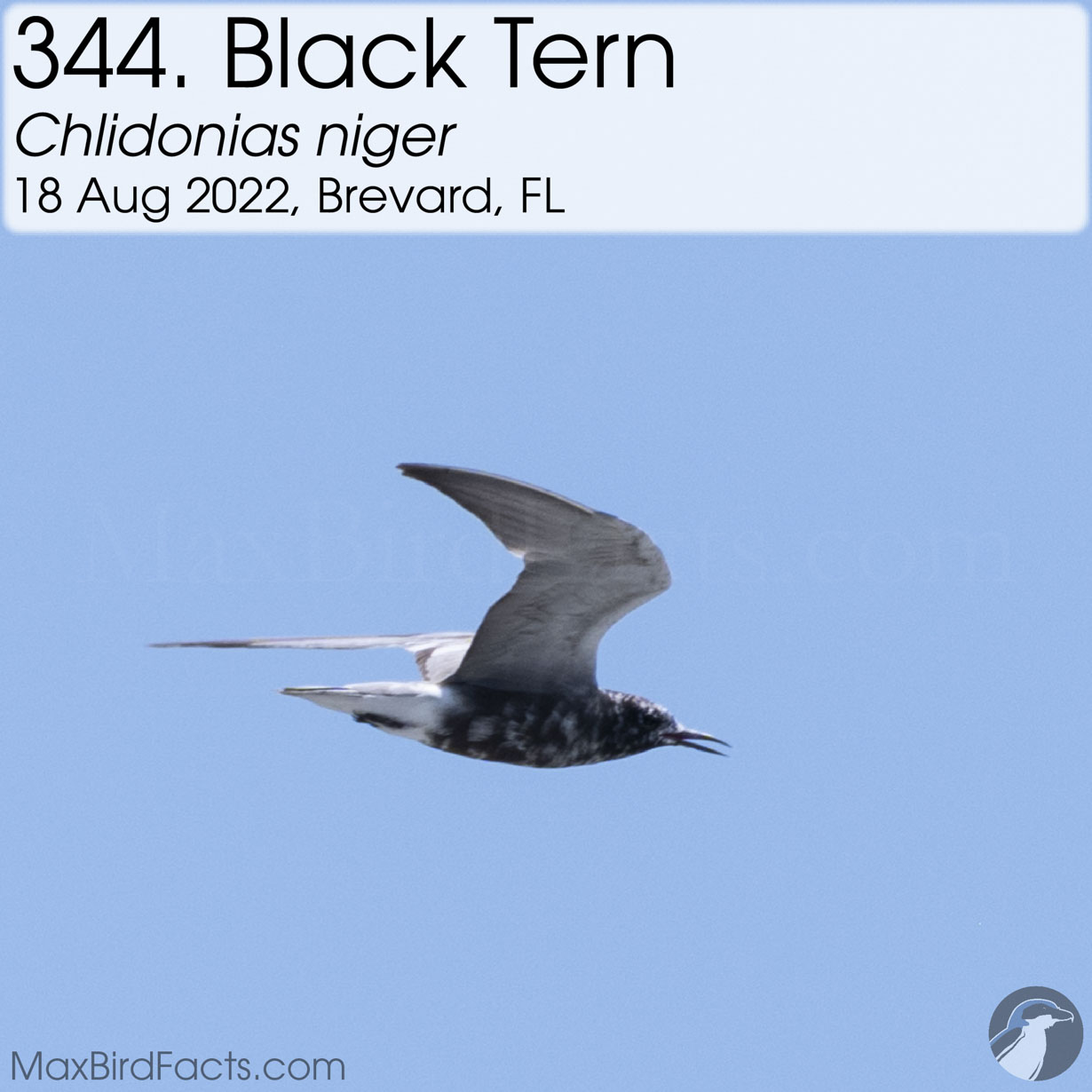

344. Black Tern (Chlidonias niger). 18 August 2022. Brevard County, Florida, United States.

The Black Tern is another relatively common and often overlooked shorebird that I checked off my life list this year. This small tern isn’t shy of coming more inland than their larger relatives. They are also highly acrobatic, diving at dizzying speed towards the water to pull up at the last second when they sense the shot isn’t right. My first sighting of them was a short flyover while photographing Magnificent Frigatebirds. A small flock of Black Terns flew in fast and low over the water, gained altitude to clear the fishing pier my dad and I were standing on and flew off into the distance. They gave us only a few seconds to see them, but this one clearly checked us out and said something to its companions while flying by.

345. Pectoral Sandpiper (Calidris melanotos). 25 August 2022. Osceola County, Florida, United States.

I still find it a little odd to find shorebirds well inland from the coast. My first Pectoral Sandpiper was out in a sod field in the middle of the state. These birds mixed with several other sandpiper species to pick and poke at the moist soil. These were tricky at first, especially if they were all alone, but they were surprisingly easy to distinguish in a mixed flock. Pectoral Sandpipers are larger than Least Sandpipers but smaller than Long-billed Dowitchers, and this intermediate size made them stand out from the crowd.

Their migration, like many shorebirds, is astounding. Their range spans across the entire North American continent, breeding in the Arctic Circle in the summer and spending the winter in the farthest reaches of South America. Their vast range only makes their visit to this little patch of grass only more special.

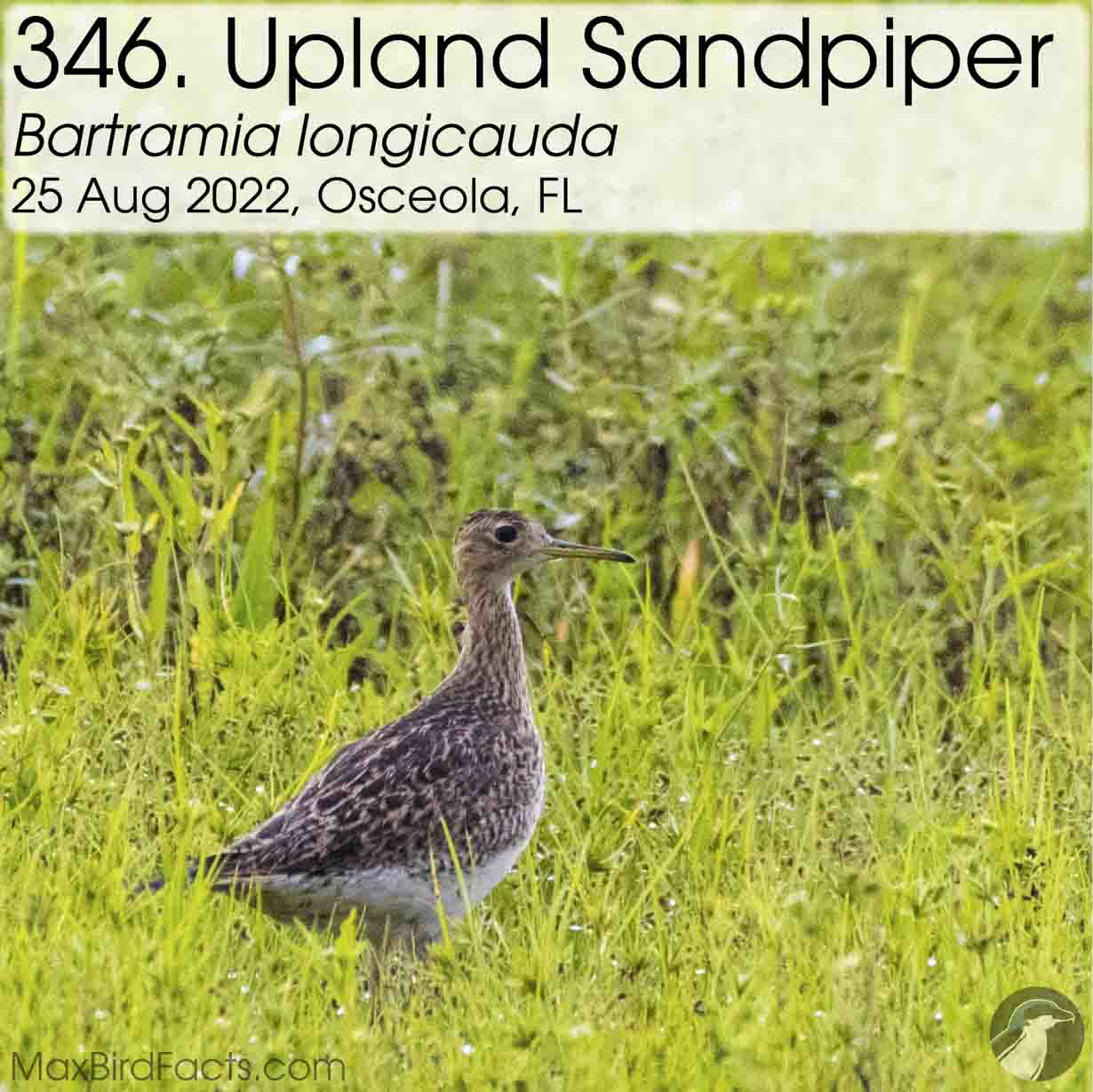

346. Upland Sandpiper (Bartramia longicauda). 25 August 2022. Osceola County, Florida, United States.

The Upland Sandpiper was another inland sandpiper for the year. Like their cousins, the Upland Sandpiper only stops by Florida on their seasonal migrations north to the US and Canada border to breed in the summer and south to Argentina to escape the snows of winter. Oddly enough, this species is almost completely landlocked and rarely wanders to the shoreline.

The best way I can describe the appearance of this species is bowling pin-like. Their small head, thin neck, and rotund bodies immediately made me think of a bowling pin. I know this might seem like a mean-spirited remark, but these familiar shapes are great to use when explaining what to look for with less experienced birders.

347. American Golden-Plover (Pulvialis dominica). 09 September 2022. Orange County, Florida, United States.

The American Golden-Plover is a species I still want to make some better images of. These medium-sized shorebirds break the typical mold of their relatives by staying more inland rather than coastal. However, like their coastal cousins, the American Golden-Plover has an enormous migratory range. These birds fly into the farthest reaches of the Arctic Circle to breed in the summer, then rocket back down into the pampas of Argentina in the winter.

These birds, with a wingspan of just over two feet and weighing about six ounces, fly a round trip of 20,000 miles yearly. To put this into perspective, the circumference of the Earth is 24,901 miles. And, if the bird lives to 13 years as the oldest wild individual did, it could travel 260,000 miles, or 10.44 times around the globe!

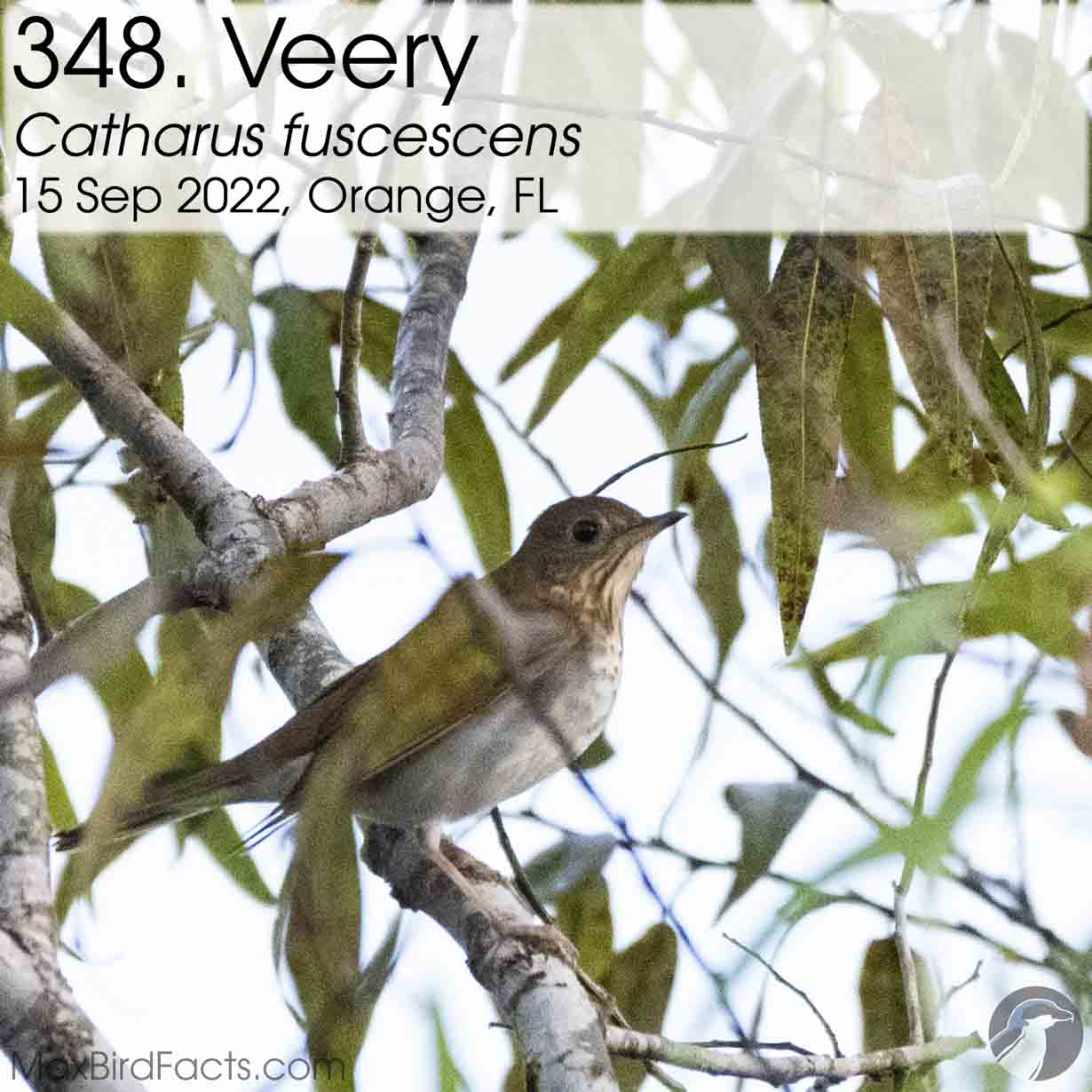

348. Veery (Catharus fuscescens). 15 September 2022. Orange County, Florida, United States.

This year I became much more aware of the incoming migrants for our Florida fall, and one target I was hoping for was the Veery. This fairly common thrush migrates through the peninsula, but I had never listed or photographed one before. One morning I set up a walk with some friends from college at the Orlando Wetlands Park; while we waited for everyone to arrive, so I did some birding. Right after picking up a few warblers and sparrows feeding, I heard a fluty call from deeper in the brush, and I spotted a Veery hop onto a slightly exposed branch. This bird stayed still for all of ten seconds, then rocketed off into thicker foliage.

I’m positive, especially with skittish birds like the Veery, that birds know when you look at them with your eyes, binoculars, or camera. This would be a beneficial survival trait for birds since it would be vital to know if a predator has spotted them. Still, I wish they knew I was just trying to capture photos of them and not make them lunch.

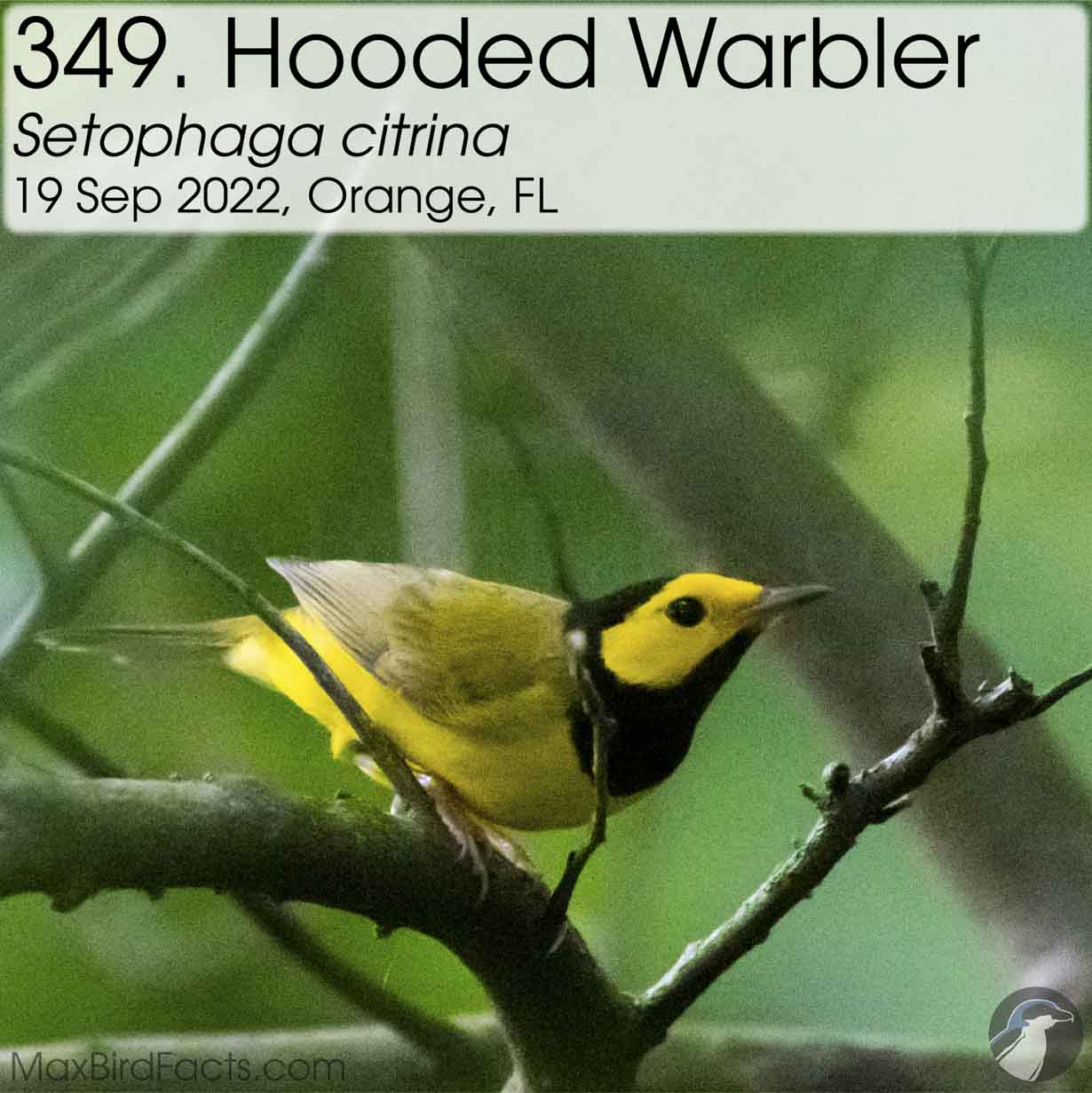

349. Hooded Warbler (Setophaga citrina). 19 September 2022. Orange County, Florida, United States.

Warblers are particularly satisfying when I get a decent look at one. This Hooded Warbler was a goal for a short outing for my girlfriend and eye one evening. I had scouted a location that seemed promising for good looks at male Hoodeds, so we made a short drive and walked into the habitat that looked good for them: a shallow stream with clear water, plenty of thick vegetation all around and overhanging, vast amounts of insects, and plenty of fruiting trees and berries. As soon as I started pishing, a male Hooded Warbler flew directly to us and perched, trying to figure out where the alarm was emanating. He bolted from limb to limb, trying to get a better look at us before darting down the stream and out of view. All told, we didn’t spend more than 45 seconds with this little bird, but the intensity of his interaction and curiosity at the potential threat was mind-blowing.

350. Bridled Tern (Onychoprion anaethetus). 29 September 2022. Lake County, Florida, United States.

Hurricane Ian brought horrific devastation to Florida. I still hope and pray that the people affected by this storm and Hurricane Nichole are recovering and getting their feet back under them. The storm wasn’t as bad as initially expected for us in Central Florida. We had prepared for several days without running water, electricity, flooding, and other necessary precautions, and fortunately, we only lost power for three days.

So, with no power and nothing really to do, Kayla and I went birding. My dad was running around Marion County and found scores of seabirds blown in by the hurricane, so we started looking for them here in Lake County. It didn’t take us long to find our first Royal Terns way farther from a body of water than I would have expected, and soon we were spotting extremely odd birds for the state’s center. Caspian, Royal, Sandwich, Forster’s, Common, Black, Bridled, and Sooty Terns hunted over Lake Eustis’s waters. At the same time, Magnificent Frigatebirds broke the horizon while foraging in the center of the lake. Many of these species were being picked up all around us in neighboring counties, and they were well worth the cold winds and sharp rain we stood through for them!

351. Sooty Tern (Onychoprion fuscatus). 29 September 2022. Lake County, Florida, United States.

Standing on the edge of the boat dock, I watched three jet-black seabirds darting and dancing above Lake Eustis’s waves. When these mystery birds banked, they flashed their pure white bellies and underwings, and I knew I was looking at Sooty Terns. Just like the other seabirds, these three terns were blown in from the Gulf of Mexico by Hurricane Ian. I would have killed to get out on the water, even with the high waves, to try and get closer to these pelagic birds. Either way, I’m still amazed these birds stopped by to rest and feed in our lake.

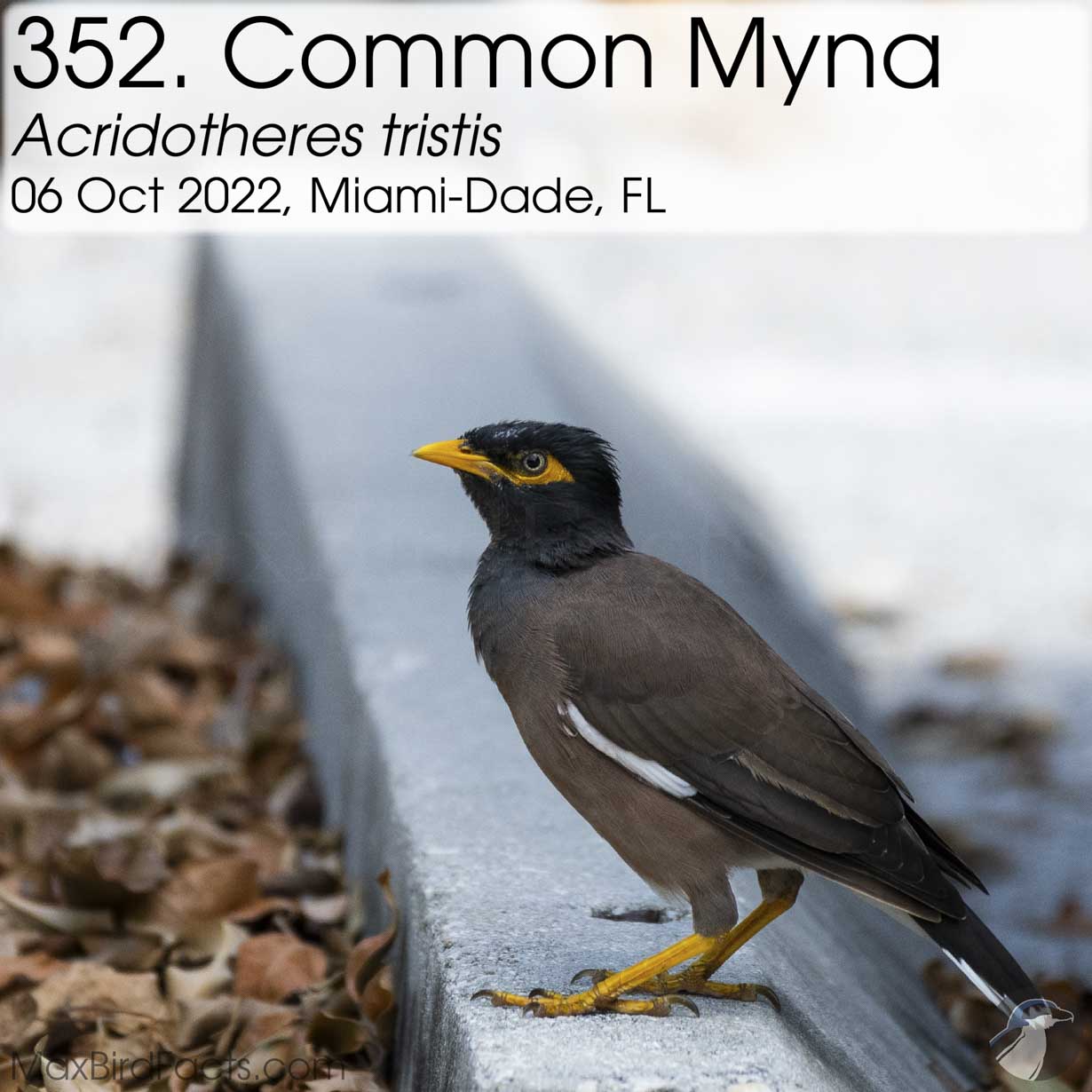

352. Common Myna (Acridotheres tristi). 06 October 2022. Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States.

The Common Myna was a minor nemesis for me this year. I originally had it as a target on my girlfriend and my’s South Florida Birding Bonanza in April, but it was one of the species that eluded us. However, I found a few locations with high, consistent counts of Myna in the Florida Keys, where my dad and I would be in October for the Florida Keys Hawkwatch. So, we marked these down and set them as secondary targets. On our first night in Miami, we stopped at an overpass that was promising for Cave Swallows (more to come on that next). While we were looking for the swallows, admiralty well out of season, my dad spotted a bird on the top of a highway exit sign. I looked at it quickly, dismissed it as a starling, and went back to scanning the concrete. Still, my dad wasn’t convinced, so we moved closer to the mystery bird and finally saw its bright yellow beak, orbital skin, legs, black head, and a brown body. We got some okay photos in the fading light, and this was good enough for my dad, but I still wanted sharper images of this exotic bird.

Fast forward a couple of days, and we are down in Key Largo on our way to the Hawkwatch, and I’m looking for places to stop for birds. I found some coordinates I had saved while researching, and we stopped across the street from a gas station where a family of Common Myna had been reported a few weeks earlier. Immediately after putting the car in park, two Myna hopped out of a bush and started clawing and pecking on the ground in front of a cigarette sign. We quickly grabbed our cameras and went across the street and counted eleven Common Myna, all scurrying around in the shade of a palm in a parking spot. It was so rewarding to see this odd bird so close and to finally have photographed it well.

353. Cave Swallow (Petrochelidon fulva). 06 October 2022. Miami-Dade, Florida, United States.

The Cave Swallow was a longshot but big target for my dad and me on our fall trip through Miami and down to the Keys. Its square tail, ruddy crown, throat, rump, and vent, sandy-white collar, belly, and underwings, and navy blue cap and back were all the identifying markers we had in mind when pulling into a residential neighborhood adjacent to an overpass they seemed to like nesting. Scanning the underpass, I couldn’t find any of the mud-dobbed nests these birds make in the fading evening light. I looked away from the bridge for a few moments and noticed something move in my peripheral vision. When I looked, six swallows were darting around chasing flying insects. I yelled at my dad to turn around, and we were able to take a few images before they flew off, chittering. Looking at the shots, we saw they matched the descriptions we had been researching almost exactly, and we marked them off our lists.

I didn’t realize it until we had seen the six Cave Swallows, but these were some of the early migrants to the Caribbean and Mexico, and these birds were very far behind their companions. I wonder if these were first-year birds and were afraid to leave their home nest, or maybe they were older individuals that didn’t want to make the long flight again. Regardless, I’m thankful they stayed a little longer for us to view, photograph, and appreciate them.

354. Tennessee Warbler (Leiothlypis peregrina). 07 October 2022. Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States.

The Tennessee Warbler was a huge pain to identify in the field. Outside the breeding season, many warbler species revert to drab, better camouflage plumage, making them a challenge to identify. The initial marking you should look for with this species versus other drab warblers is its dark eyeline. This runs approximately from the nares, through the corners of the eyes, and ends shortly behind the eye. The eyeline can help you quickly distinguish the Tennessee Warbler from the Orange-crowned Warbler, which lacks the eyeline altogether but otherwise is nearly identical. Still, without the ability to review photos on the camera’s LCD or the computer later, this would be significantly harder to identify.

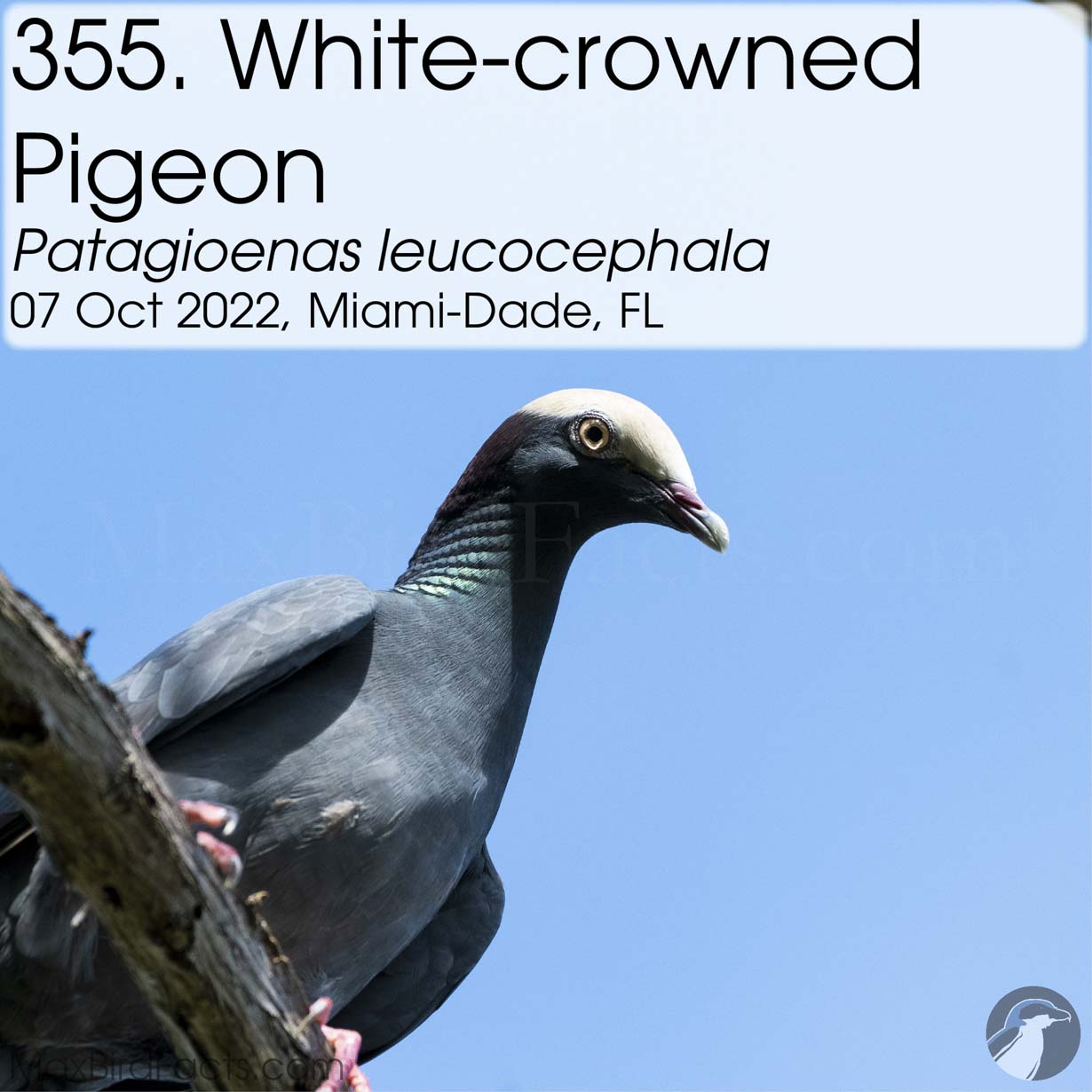

355. White-crowned Pigeon (Patagioenas leucocephala). 07 October 2022. Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States.

The White-crowned Pigeon was another failed target of the April South Florida Birding Bonanza. So, naturally, it ranked high on my list when my dad and I retraced some of our spots from this trip and looked for more farther south. Our first sighting was about what I would expect from a pigeon: brisk, swift, and fleeting. This initial bird didn’t give us any warning and just shot across a field like a bullet. I saw the dark body, white head, and black nape, so we listed it. Thankfully, these Caribbean natives were much more common in the Keys, and we saw several more before the trip’s end.

One morning at the Florida Keys Hawkwatch, my dad and I walked around the campground area looking for warblers and other small fall migrants. We found a few great birds, and walking back to the observation tower, I saw a pigeon drop into a patch of seagrapes that arched over the sidewalk. My dad and I slowly walked towards the site, but the bird must have heard or seen us and flushed. So, we walked under the brush, sat on the path, and waited for the bird to return. And sure enough, two White-crowned Pigeons flew back into the vines to feed. The two we had were one juvenile and one adult, possibly a parent teaching their child what is and isn’t safe to eat. Watching the young pigeon clamber onto a branch loaded with fruit and slowly tug at each before one would release was amazing. The bird was only eating fruit that was ripe enough to be plucked off the vine with minimal effort, ensuring it was safe to eat. Watching these pigeons so close, photographing them so well, and observing and understanding this behavior was spectacular.

356. Blue-and-yellow Macaw (Ara ararauna). 07 October 2022. Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States.

My nemesis from the South Florida Birding Bonanza was the Blue-and-yellow Macaw. This massive parrot was one of the two we missed on our trip, and I was hoping to find it in October with my dad. After a hugely successful morning in a park, I looked for recent sightings of the macaws and saw a ton of lists from the University of Miami, so we went. Driving around the parking lots and public areas of the college, we scanned the trees and sky for these flying gems.

I put my speaker on the roof of the car, playing a flight call while we drove around one parking lot, and two macaws came screaming past. These two birds flew a little ways away from us, but even through the trees, we could see their brilliant colors. We raced to an opening to try and spot them, but they were gone as quickly as they arrived. It was a bitter-sweet moment, seeing and being able to mark this species off my life list but not having a photo with it. But, you can’t get them all.

357. Canada Warbler (Cardellina canadensis). 07 October 2022. Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States.

The Canada Warbler might be the most insane find of the year for me. Walking around a rather run-down agricultural site that people only seemed to use for riding dirt bikes and drinking beer, my dad and I were hunting for Smooth-billed Ani. Unfortunately, no Ani appeared, and we walked back to the car, defeated. Driving out, I saw a few small birds fly from the side of the dirt road into thick grass. I hopped out and started pishing, and two Clay-colored Sparrows instantly popped into the top of the grass with their crowns raised in alarm. I stopped pishing, let them calm down, and saw something else moving lower in the grass. My immediate thought was a male Common Yellowthroat, so I resumed pishing, but the bird barely reacted besides freezing. I was able to focus through the grass enough for a halfway decent photo and started comparing it to a guide.

The only bird that appeared to have the white ocular ring, primarily black crown and lores separated by yellow, a bright yellow throat and breast, blue-gray rear crown, neck, back, and tail, and pinkish-orange feet and legs. I listed this and initially posted a photo of my camera’s LCD for the reviewer, and it was almost instantly confirmed. Looking at the eBird stats for this warbler, I found it has only been seen in Miami-Dade County 73 times and photographed 44 times, meaning I hold 2.27% of all confirmed photographed sightings of a Canada Warbler for this county!

358. White-tailed Kite (Elanus leucurus). 07 October 2022. Miami-Dade County, Florida, United States.

I didn’t earn many new raptors in 2022, but the ones I got are spectacular. The White-tailed Kite was another missed target from the April South Florida Birding Bonanza, and I had almost written them off for the migration by the time my dad and I would make it down in October. However, running off the high from finding the Canada Warbler, I saw a group of raptors in a kettle low over the road ahead, and one stuck out from the rest. When looking through the binoculars, I thought this was a Mississippi Kite, but it was way too white. Then my brain caught up, and I realized the bird I was looking at was the White-tailed Kite that had eluded me before!

I screamed at my dad to stop the car, and before he could, I jumped out the door with my camera. This stunning kite flew directly over us in a deliberate, low flight, giving us an amazing view. These raptors aren’t rare in South Florida, but they are much more common throughout California, Mexico, and parts of the Caribbean and South America. When editing these photos, I noticed this bird has a full crop. The crop is an outgrowth of the esophagus that birds use to store food when they don’t want to consume it immediately. I hope this means this adult was flying home for the night with a meal for its hatchlings.

359. Blackburnian Warbler (Setophaga fusca). 08 October 2022. Monroe County, Florida, United States.

The Blackburnian Warbler I got this year was a nice surprise. Going through photos at the end of the day, I noticed a shot of a warbler’s legs that were not matching the other species we had listed. It had two prominent wing bars, spotty stripes down the sides, clean white vent, white undertail, gray legs, and yellow feet. After almost an hour of looking through guides and comparisons, the only bird I could make it fit was a female Blackburnian Warbler. The males have a radiant orange face and throat, but the females are much plainer, as typical for songbirds. Shots like these reinforce my mantra of photographing everything because you never know if it’s something you weren’t expecting.

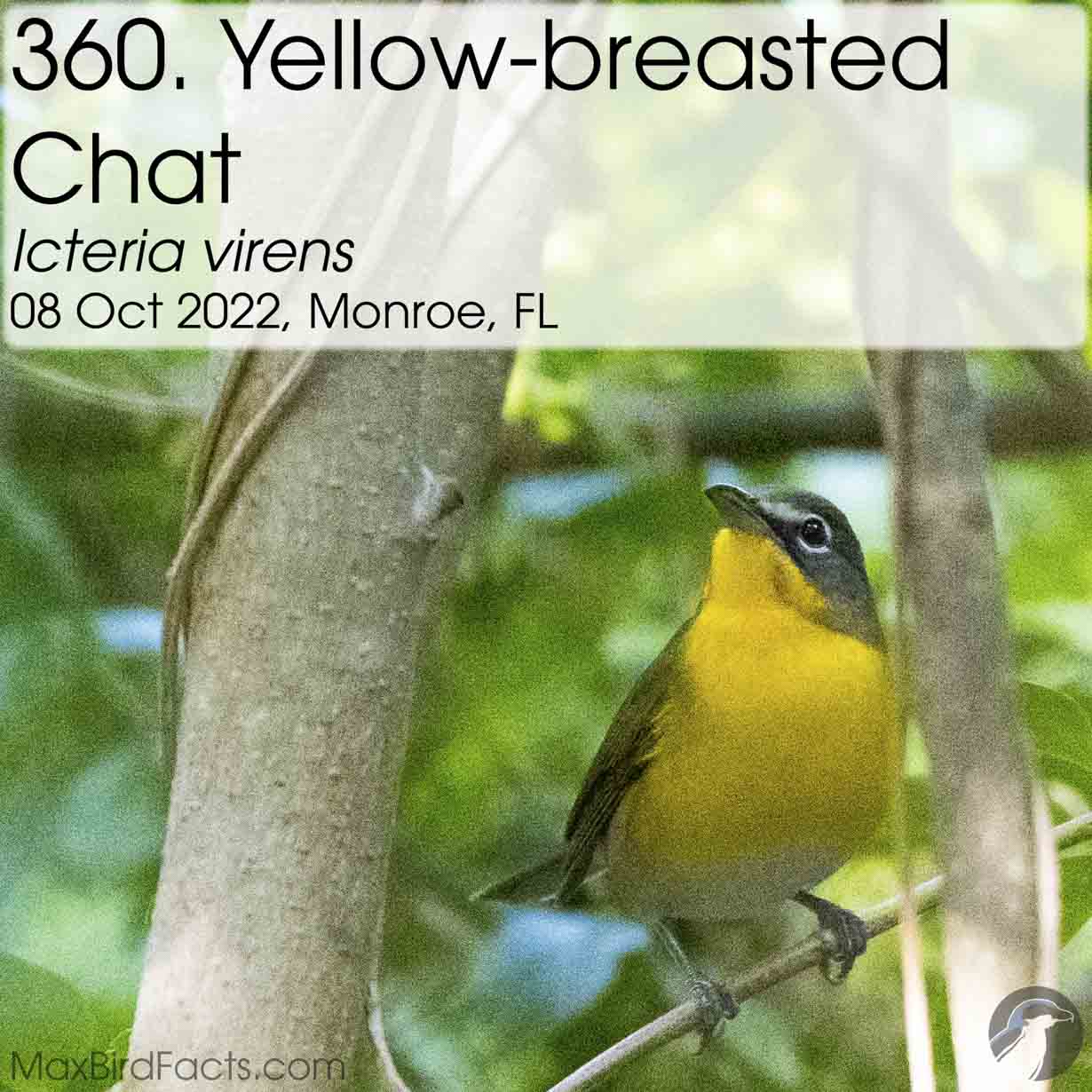

360. Yellow-breasted Chat (Icteria virens). 08 October 2022. Monroe County, Florida, United States.

Another surprise bird for the Florida Keys trip my dad and I made in October was a brief visit from a Yellow-breasted Chat. These extremely reclusive birds are quite interesting from a genetic and taxonomic standard. Originally, they were placed with other New World Warblers in the Parulidae family. However, studies on this bird proved it didn’t fit the genetic mold of any preexisting group, so the family Icteriidae was formed. This sounds very similar to the Blackbird family (Icteridae), and that is because the Yellow-breasted Chat is taxonomically most related to blackbirds rather than warblers.

The confusion doesn’t end there since these birds are also skilled mimics. Mimicry in the avian world isn’t rare, but it is most commonly thought of when considering Mockingbirds, Catbirds, and Thrashers (the family Mimidae). However, this would only be down to the convergence of this shared behavior between the two species since they are nowhere near related. Mimicry can be vital when trying to scare off predators or competition.

This mimic was very interested in the commotion my dad and I were stirring up with the vireos, warblers, and other songbirds. It came, perched a few dozen yards in the brush, and watched us, making the occasional soft call. It surprised me how hard this bird was to locate after taking my eyes off it. Even with its bright yellow breast, the Chat was stone still and hid incredibly well among the foliage.

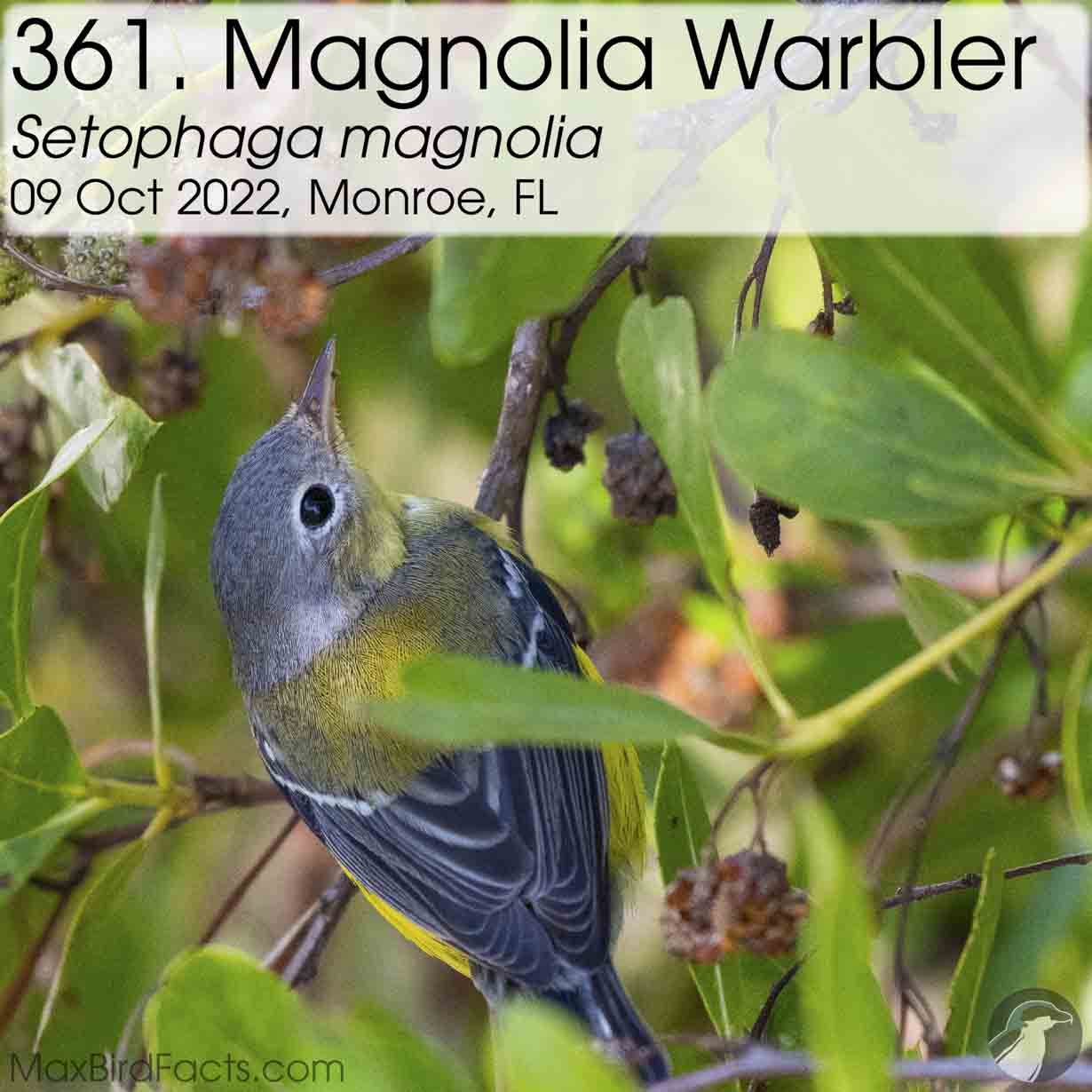

361. Magnolia Warbler (Setophaga magnolia). 09 October 2022. Monroe County, Florida, United States.

The Magnolia Warbler is a species I’ve wanted to see all year. My dad and I use the Sibley Birds 2nd Edition as our primary field guide, and it has a beautiful male Magnolia Warbler on the cover. Unfortunately, I have not seen or photographed a male Magnolia, but I saw my first female at Hawkwatch.

Walking to a small opening surrounded by high mangroves, we saw a small warbler flutter out and then perch on the edge of a tree. We trained our cameras on her and immediately called it a Magnolia Warbler. This female was easily fifty yards away, and we got some good images of her foraging among the leaves. However, when we climbed the steps to the Hawkwatch, a few birders told us a female Magnolia was in the tree at eye level to the platform. I waited for her and she popped back out and I grabbed a few more images, and they turned out much nicer than the previous bird. It’s fun but also a little annoying to mark off a lifer twice within 10 minutes when you’ve been looking for it all year.

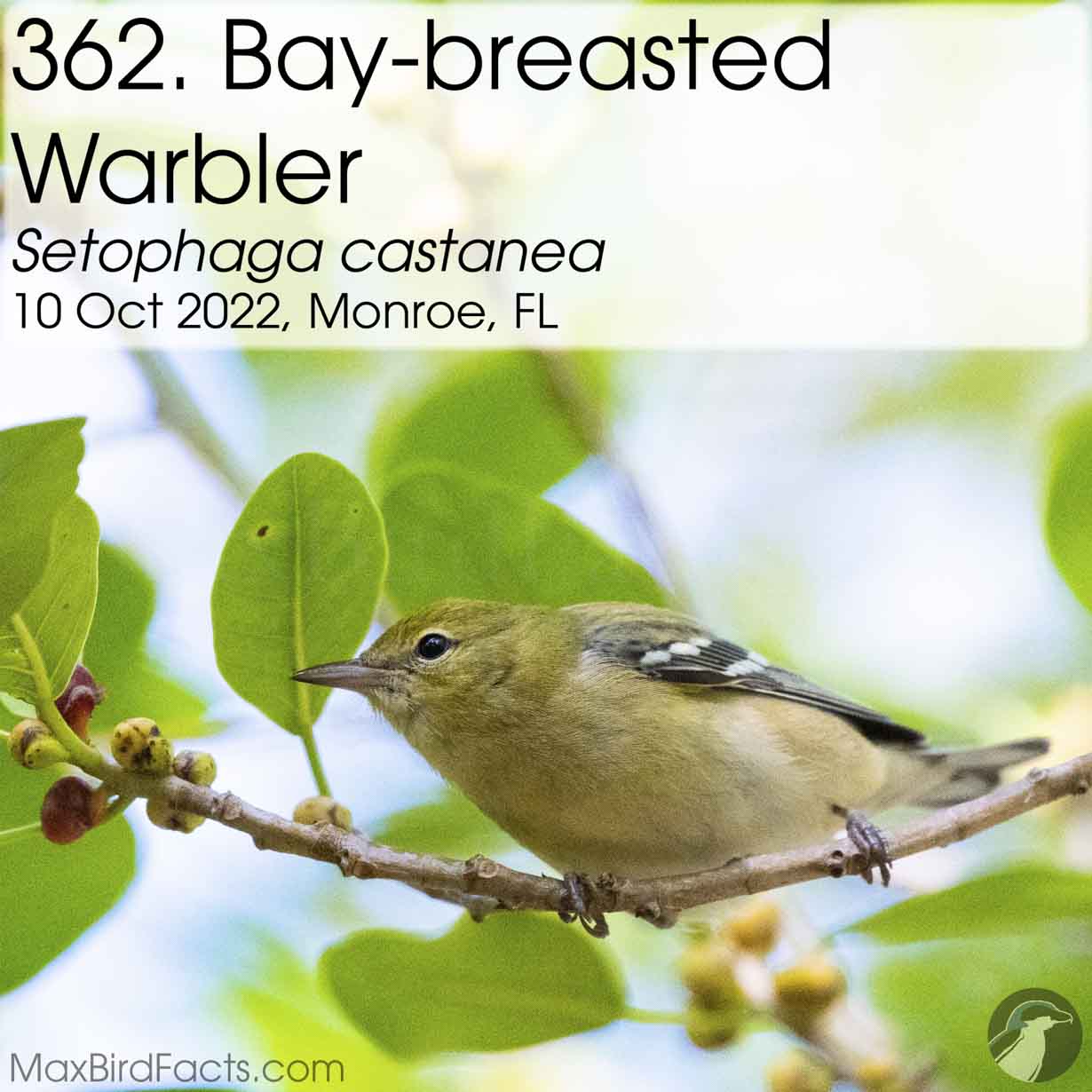

362. Bay-breasted Warbler (Setophaga castanea). 10 October 2022. Monroe County, Florida, United States.

I wish we could have spent a week under the trees at Fort Zachary Taylor. There was a massive gathering of songbirds in those woods, feeding on the fruiting trees and staging for the last leg of their migration south. Trying to photograph all of these birds bouncing around was insane. In one instant, I would be looking at a Black-throated Blue Warbler, then a Northern Waterthrush would jump in front of my lens, then another species and another would join the chaos.

The Bay-breasted Warblers were in the thick of this confusion. We spotted two individuals, a male and a female. This couple was probably grabbing a quick snack before jumping down to Cuba. The female Bay-breasted is another drab warbler and a challenge to identify. The best feature to look for when differentiating these is their lack of streaks on the breast. Both Pine and Blackpoll Warblers, the most visually similar species, always show some of this vertical streaking.

363. Swainson’s Thrush (Catharus ustulatus). 10 October 2022. Monroe County, Florida, United States.

The Swainson’s Thrush was a super lucky bird at Fort Zachary Taylor. Another migrant bird heading to the tropics to escape the cold northern winter, this bird was a huge surprise to see. Walking down the path, I was photographing a male American Redstart when I saw a larger bird fly in and land on a branch a few yards away. I slowly positioned myself for a clear shot and took a couple of images. I tried to get my dad’s attention, but he was distracted by the hordes of warblers in the trees around us. After the thrush took off, I looked at the photos more carefully and saw a Swainson’s Thrush’s distinct buff-colored eyering, spotted breast, and clean belly. Seeing this bird so clearly was a true blessing.

364. Gray-cheeked Thrush (Catharus minimus). 10 October 2022. Monroe County, Florida, United States.

A second thrush in the same patch of woods! My dad and I honed in on a thrush that landed in a tree just off the path. I was about twenty yards from my dad on a hill while he was on the path just below the tree the bird landed. I took some decent photos before it took off deeper into the woods, and I noticed how different this looked from the Swainson’s earlier. It seemed to have sooty cheeks, a much whiter throat and breast, and an overall duskier brown aspect. I looked through my guide and saw this all matched perfectly for the Gray-cheeked Thrush, so I added it to the list. Like the Swainson’s, the Gray-cheeked was surprisingly cooperative for a thrush. It stayed fairly still for several minutes while we moved around to try and get a better view of it. I imagine it was trying to conserve energy before making the flight to Cuba, which is why it wasn’t as skittish as other thrushes I’ve seen.

365. Philadelphia Vireo (Vireo philadelphicus). 10 October 2022. Monroe County, Florida, United States.

The Philadelphia Vireo was the primary target of Fort Zachary Taylor. As soon as we got there, I started focusing on finding vireos and quickly located a group of Red-eyed Vireos working a tree. Looking around this area, I spotted a bird that was surprisingly all alone. Once I focused my camera on it, I knew this was our bird. I got my dad’s attention, and we both photographed it for several minutes until we knew we had some excellent photos.

The images confirmed our suspicions: the bird’s gray crown, black stripe through the eye, white above and below the eye, and brilliant yellow from its throat to the tail. This bird was a straggler; most of its relatives had already jumped to the Yucatan peninsula earlier in the season. However, I’m delighted it waited for us to visit the fort before it continued its journey south.

366. Western Tanager (Piranga ludoviciana). 19 October 2022. Lake County, Florida, United States.

The Western Tanager was my bigfoot sighting of the year. Scouting Emeralda Marsh for the upcoming North Shore Birding Festival, I stumbled into a party of migrating songbirds. As I rounded the corner of the path, I saw a mixed flock of Painted Buntings, Indigo Buntings, Blue Grosbeak, and a bird I didn’t quite recognize. I brought up my camera and got two shots before the whole flock took off. Unfortunately, I didn’t have much time to think about it at the time since the tree above me was filled with warblers. However, when I got home and downloaded the photo, I saw what I initially didn’t catch. I spent three hours pouring over field guides, websites, and whatever else I could think of to try and explain this bird, and the only one that I kept coming back to was the Western Tanager.

I’ll be the first to admit it, this photo is garbage quality. It is entirely unfocused, the lighting is atrocious, and the shade gives everything a yellowish hue. However, the apparent red-orange color on this bird’s head, yellow throat and breast, black wing coverts, and just the slightest hint of wing bars make me confident this was a Western Tanager. More minor features like the bird’s posture and beak shape only reinforce my opinion. Around this time, there were a handful of sightings of this same species both north and south of here.

367. Helmeted Guineafowl (Numida meleagris). 23 October 2022. Marion County, Florida, United States.

The Helmeted Guineafowl was a driveby bird. Driving home from my parent’s house, I saw two rotund birds with small blue heads and a black body dotted with white. If there wasn’t a train of cars behind me, I would have slammed on my brakes and tried to get a photo with my phone. I made an incident report for these and planned to return the next day.

When I did, all I found were the turkeys I had spotted with the guineafowl. This was both good and bad. On the one hand, I didn’t see my bird to photograph it. However, this also meant these weren’t captive birds and were probably escapees from a nearby farm, making them fair game to list. It’s pretty cool when you can list an African bird on your drive home.

368. Bachman’s Sparrow (Peucaea aestivalis). 05 November 2022. Lake County, Florida, United States.

As the year wound to an end, I was gaining on the top three list for Lake County. So, looking for spots with good potential, I found an area that seemed excellent for woodpeckers. While I was out there, I listened for other songs, and a Bachman’s Sparrow gave me a tsip call. I spent at least half an hour trying to get this bird to show itself, but it wouldn’t budge from its hiding place.

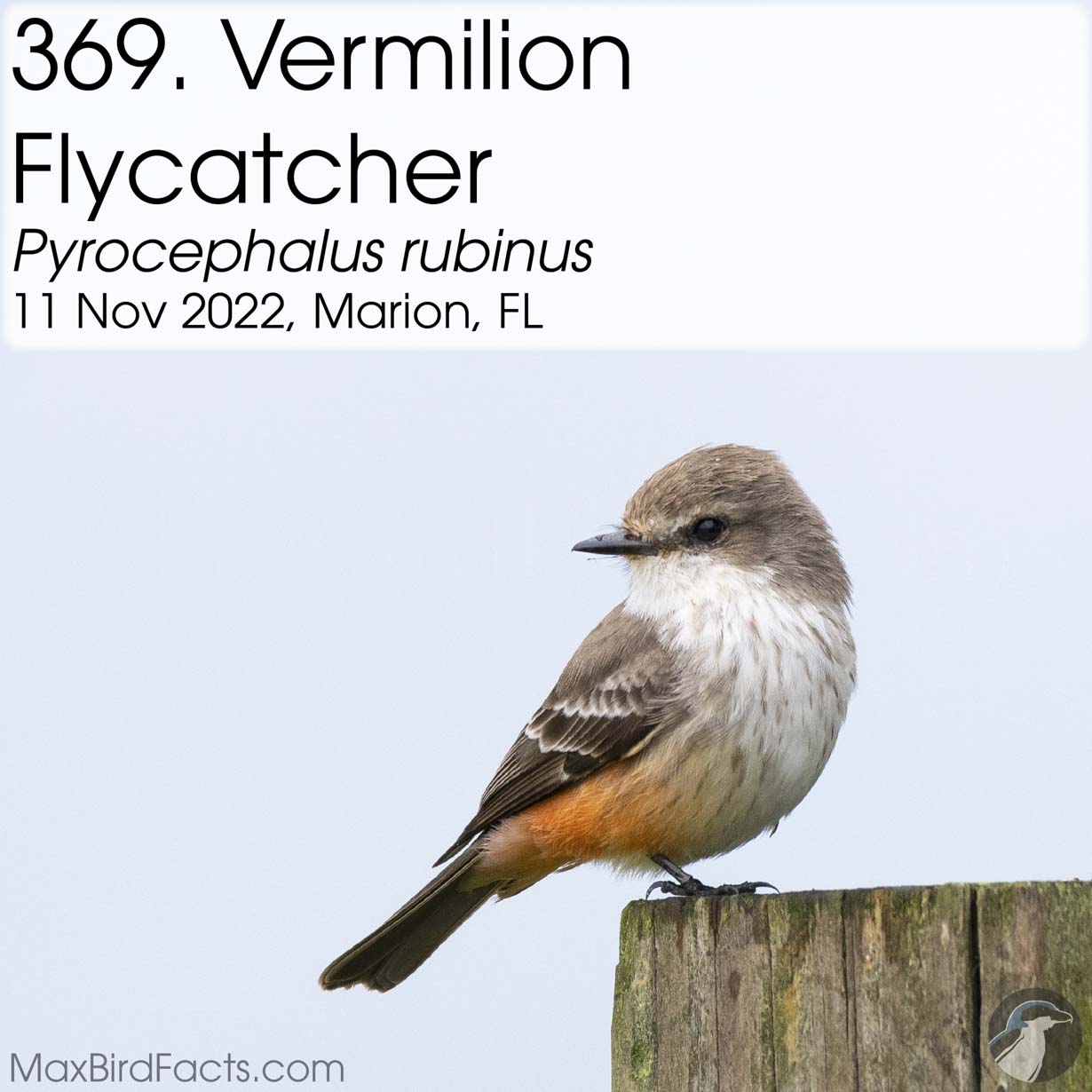

369. Vermilion Flycatcher (Pyrocephalus rubinus). 11 November 2022. Marion County, Florida, United States.

The Vermilion Flycatcher was a bird I’ve tried to get several times, but each was unsuccessful. So, when one was listed a few dozen times with some great images posted, I decided to spend an entire day out hunting this bird. As soon as I parked my truck, I started walking to where she had been reported. Unfortunately, roughly halfway between my car and the tower the flycatcher was hanging around, the clouds unloaded all of their rain and soaked me to the bone. I walked through the downpour, but it cleared up when I was a few dozen yards from the tower. As I got closer, I saw a bird perched on a sign, and I got my hopes up that this was my bird.

Once I was close enough to photograph it, I saw this was the Vermilion. Her salmon-pink vent, soft streaked white breast and belly, warm gray crown and back, and dark wings and tail all pointed to her being my target. She was an exceptionally cooperative subject, too; I got within a couple of yards from her, and she was posing calmly the entire time. On several occasions, she would take off, grab a flying insect, land back at the same perch, and gobble down the bug. Watching this rare bird so closely and with no apparent fear of me was such a special moment.

370. Least Flycatcher (Empidonax minimus). 14 December 2022. Lake County, Florida, United States.

The Least Flycatcher was a bit of a disappointment. During the North Shore Birding Festival, this bird had been listed dozens of times. So, I drove out to where it was being sighted. I got to the boat ramp and started looking for good perches this little bird would prefer. Across the channel, a small bird was giving somewhat quiet pijerrr calls. I played the mirrored Least Flycatcher call, and it immediately reacted by flying high above the tree it was perched, hovering, calling several times, then dropping back down. The light was too low, and the bird was too far to pick up a clear recording, but I know what I heard matched the call I played back, and that bird’s reaction was way too strong to be an Eastern Phoebe.

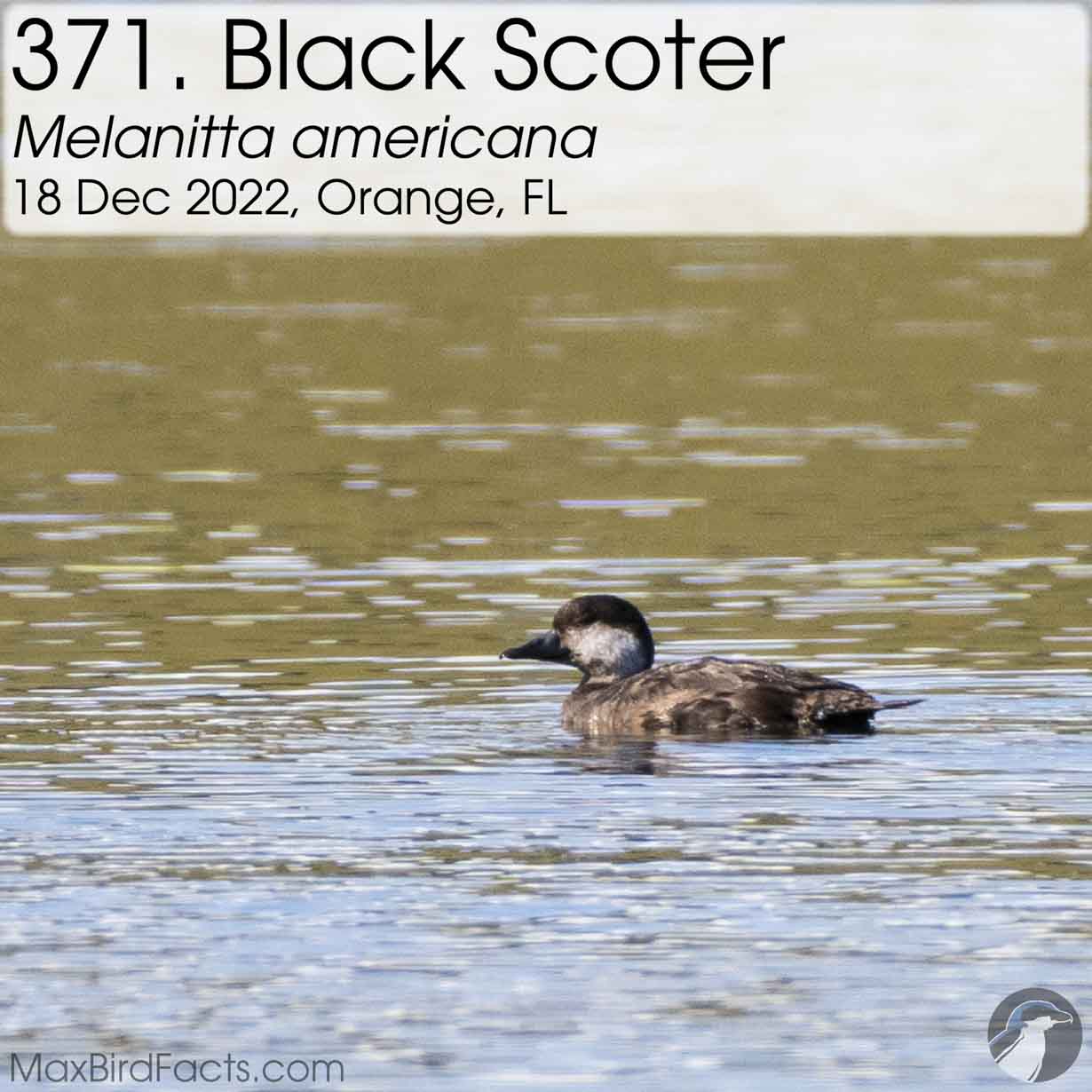

371. Black Scoter (Melanitta americana). 18 December 2022. Orange County, Florida, United States.

The Black Scoter was a bird of convenience. Talking to my dad the day before, I saw a handful of listings for a Green Peafowl about an hour south of me. So, I planned to make the drive out for it and hopefully mark it off my and my girlfriend’s lists. The morning I planned to leave for the peafowl, I saw a rare bird alert for a Black Scoter, which fit perfectly in line with our route.

When we got to the sportsplex this sea duck was reported in, we started scanning every bird that was in the water. We had some fantastic views of the dozen or so Bonaparte’s Gulls flying around the lakes and the Hooded Mergansers that were rafting on the edges. Looking back to the listings of our target, I saw they all mentioned the “back pond,” so we started walking. Once we got to this body of water, I started scanning again. There was another large group of mergansers, three Lesser Scaup, and what looked like a Ruddy Duck with its head tucked. When I looked back at what I initially called a Ruddy, I saw its cheeks weren’t as white as I would expect, its tail wasn’t as pronounced as usual, and its bill seemed very off. Then, it clicked that this was our target duck, and I don’t even want to think of how many photos I took of it.

The bill on this bird was the main tell for me. A Ruddy Duck’s bill is very typical for a duck (round and flat with slightly downward curled edges). However, this female Black Scoter had a much broader base and a very pronounced hooked tip to her bill. This is a perfect tool to pry clinging prey off rocks in the ocean. She was an exquisite addition before the year’s end.

372. Green Peafowl (Pavo muticus). 18 December 2022. Orange County, Florida, United States.