If you’ve read any of my articles, I’m sure you’ve noticed the use of a bird’s scientific name. This use is even more apparent with some of my species highlight articles, like 18 Confounding Facts About Kingfishers, where I discuss several meanings and origins of this family’s names.

And even the term “Taxonomy” has its roots in Greek; taxis meaning arrangement, and nomos meaning method. Simply put, scientists love to classify and reclassify anything using ancient or dead languages to the point of tedium.

In this article, we will examine some basic biology focusing on Taxonomy and Systematics. This will be slightly more technical than some of my other works, but I think it is vital if you want to better appreciate and understand the natural world.

So, let’s dive into the biological field of Taxonomy!

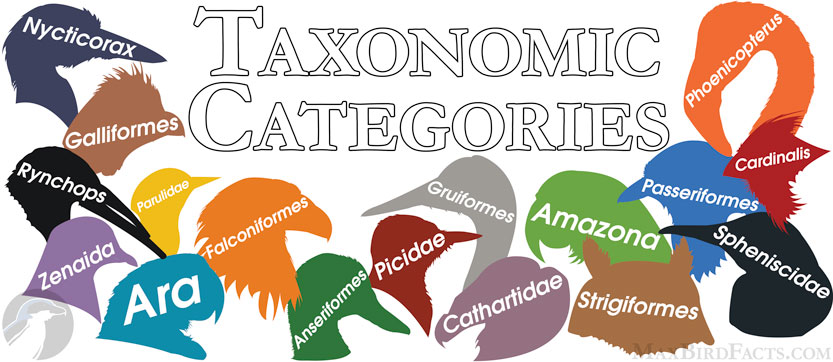

What Are The Taxonomic Categories?

Taxonomy is the branch of science focused on the classification of all living things. This classification can be as broad as plants, kingdom Plantae, versus animals, kingdom Animalia. It can also be so acute down to the genus or species level, like the Loggerhead Shrike (Lanius ludovicianus).

The currently most utilized form of Taxonomy is called Linnaean classification, where each level contains more and more similar species. This classification is broken down into eight groups: Domain, Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, and Species.

Let me share a mnemonic I learned in 7th grade that’s stuck with me today for remembering the order of these layers:

- Dear (Domain)

- King (Kingdom)

- Philip (Phylum)

- Came (Class)

- Over (Order)

- For (Family)

- Good (Genus)

- Soup (Species)

These similarities were initially based on the animal’s physical, morphological, and behavioral attributes, such as its skeletal structure, similar ecological niches, or simply color and appearance. That method was fairly accurate, but scientists use genetics to restructure and refine taxonomic groups today.

Let’s use the Loggerhead Shrike (Lanius ludovicianus) as a learning tool to better understand Taxonomy.

First, the shrike is an organism comprised of multiple cells, each of which has a nucleus, so it falls under the domain Eukaryota for eukaryotes.

Second, this multicellular organism breathes oxygen, consumes organic material, reproduces sexually, and develops from the blastula (a hollow sphere of cells), so this is an animal, placing it in the kingdom Animalia.

Next, this animal has a spinal cord, also called a hollow dorsal nerve cord, a notochord (flexible rod vital to vertebrate development), thyroids (hormone-producing glands), pharyngeal slits (slits along the throat, typically only seen in embryonic development for terrestrial animals), and a post-vent tail (an extension of the spinal cord past the excretion aperture) pointing to this belonging to the phylum Chordata for chordates.

The animal is warm-blooded (homeothermic), has feathers, a toothless beak, a four-chambered heart, a high metabolic rate, pneumatized (hollow) bones, and lays eggs with a hard calcified shell, so it is a bird, class Aves.

This bird has an anisodactyl toe arrangement (three forward and one back), has altricial young (blind and helpless after hatching), a complete nasal septum, and ten primary flight feathers and ten-to-twelve rectrices (tail feathers), placing it into the order Passeriformes for songbirds.

The songbird is medium-sized compared to other members of this order, has a sharply hooked beak with a tomial tooth (a ridge on the upper bill near the tip used to increase bite force), is fully carnivorous, and impales its prey on thorns or barbed wire to “butcher” them, so this is a shrike in the family Laniidae.

This shrike perches conspicuously, prefers more open habitats, performs the hawking hunting style (flying out from its perch to capture prey and returning to that perch), is solitary outside of the breeding season, and appears more like the majority of its relatives, placing it into the genus of true shrikes, Lanius.

Finally, this true shrike has a peculiarly large head for its body, is only found in North America, has a plumage of gray above and white below, a black mask, beak, and wings, and distinct white windows on the primaries, pointing to this being a Loggerhead Shrike, species ludovicianus.

So, to fully show the classification of the Loggerhead Shrike, it would be listed as Eukaryota Animalia Chordata Aves Passeriformes Laniidae Lanius ludovicianus.

However, writing all this when talking about this species would be a waste of time and ink, so the simple binomial of the organism’s genus and species name, Lanius ludovicianus, is more than adequate.

You might even see the binomial name condensed further to the first initial of the genus, followed by the whole species name (L. ludovicianus). This shortening is used extensively using a trinomial name for subspecies, like the South Florida Loggerhead Shrike subspecies Lanius ludovicianus miamensis, or shortened to L. l. miamensis.

I know that seemed excessive, but citing these intricate details is vital to separating one species from another.

An example of the importance of detail when defining a species is the famous “featherless biped” incident between the Greek philosophers Plato and Diogenes. The story goes that when asked what a human is, Plato replies that a human is a featherless biped since birds were the only animals known to the Greeks to walk on two legs. Diogenes, a staunch cynic, came back to the school with a chicken plucked clean and announced, “Here is Plato’s man!”

This simple story from ancient Greece shows us that we need a correct and detailed description of what makes one thing unique from another to prevent confusion.

The simple fact is that the smallest difference could be the gap needed to prove a group of animals is a distinct species. This rings even more true with birds, where the slightest difference in pitch in their song could isolate a group from the main population.

So, now that we know the basics of Taxonomy let’s discuss how organisms are sorted into their groups.

What Is A Family?

The way we all define family is a group of people you are related to by blood or genes. So, what does “family” refer to in a biological sense?

The systemic definition of family is a group of organisms sharing similar features or genes that are more alike than members of their order but less similar than those of their genus.

Essentially, this organization system aims to decrease the differences between similar species as you progress from order to family or family to genus.

For example, both Peregrine Falcons (Falco peregrinus) and Crested Caracaras (Caracara plancus) are members of the family Falconidae.

However, the Peregrine is a fast-moving, surprise attack hunter with sharp wings and a perfectly aerodynamic body, causing it to fall under the genus Falco for true falcons.

Compare this to the Crested Caracara with its rounded wings, longer legs for walking on the ground, broad utilitarian beak, and bare facial skin cause it to belong to the genus Caracara.

So, with this example, even though these two birds belong to the same family, there are still more than enough differences between them to continue the refinement process.

This refinement can even continue down to levels between the standard eight, making classification accuracy nearly infinite. To put this into perspective, there are seven subsections of the level of Order, four before the official Linnaean classification and three following it. Here is that order:

- Magnaorder

- Superorder

- Grandorder

- Mirorder

- Order

- Suborder

- Infraorder

- Parvorder

I won’t bore you with every sublevel of Linnaean classification.

Yes, they are vital to clean up the divisions between similar yet distinct groups of animals within their original levels. Still, there are far more than most of us will ever need to deal with.

However, one I will touch on is the use of subspecies.

What Is A Subspecies?

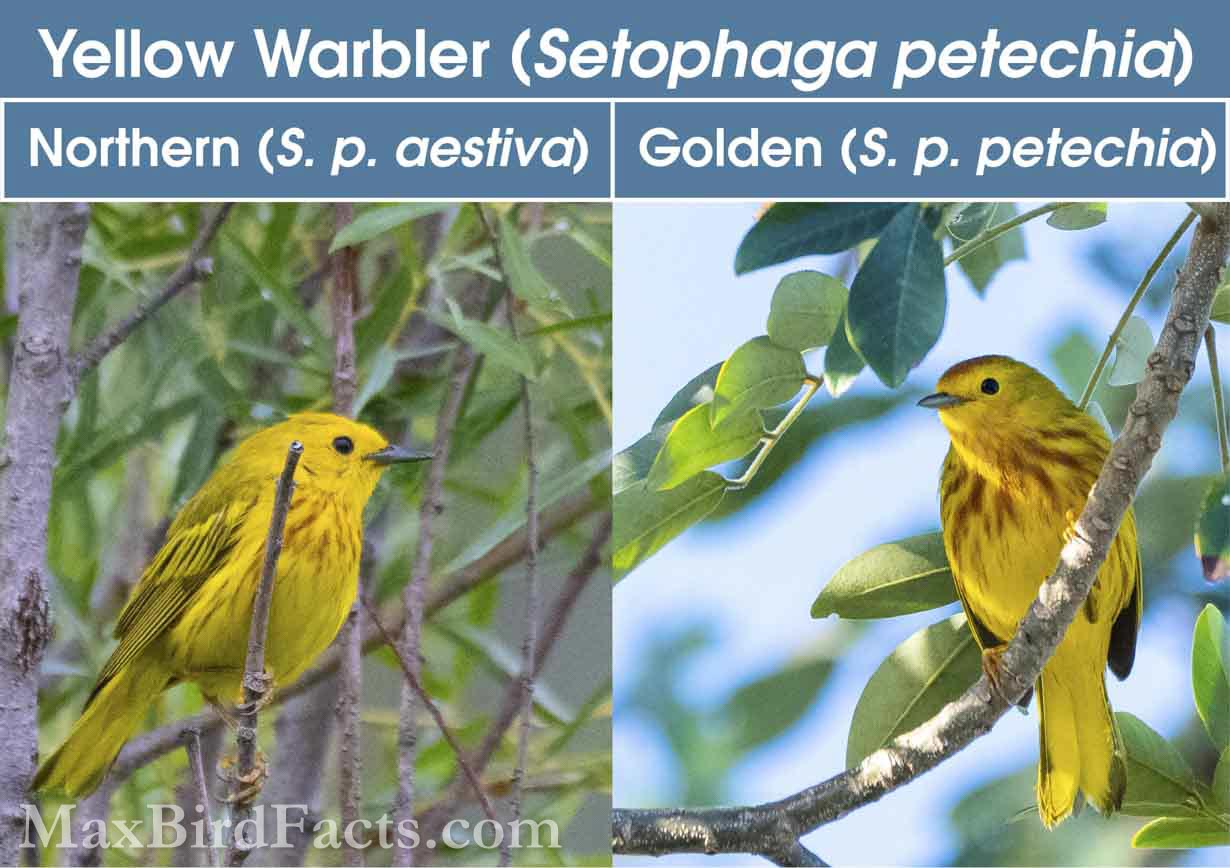

A subspecies is the subsection below the species level of Linnaean classification where distinct differences exist between populations within that species.

Geographic isolation is the typical catalyst of these distinctions. Newly formed mountain ranges, changes in wind currents, the widening of rivers, or tectonic shifts moving landmasses apart can cause populations to become geographically isolated enough to start to become unique.

These changes can range from obvious changes in song pitch, length, and frequency, or the subtlest amount of a change in the hue of the feathers around the eyes. The bird’s diet shifting more towards one food source than their original population could also indicate that they are becoming a distinct population from their parent species.

One of the best places to see evolution by natural selection in action is on islands.

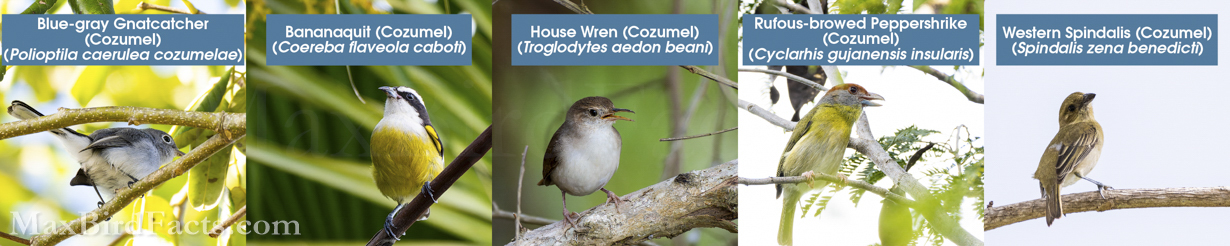

Even a simple trip to Cozumel, Mexico, can easily land you several subspecies that are either nonexistent or difficult to find on the mainland.

On a trip to Cozumel on January 2023, I listed ten subspecies, five of which were endemic to the island:

- Blue-gray Gnatcatcher (Cozumel) (Polioptila caerulea cozumelae)

- Bananaquit (Cozumel) (Coereba flaveola caboti)

- House Wren (Cozumel) (Troglodytes aedon beani)

- Rufous-browed Peppershrike (Cozumel) (Cyclarhis gujanensis insularis)

- Western Spindalis (Cozumel) (Spindalis zena benedicti)

This isn’t even considering the distinct species arising from their isolation on islands. While birding Cozumel Island, we found two species that exist nowhere else on Earth, the Cozumel Emerald (Cynanthus forficatus) and Cozumel Vireo (Vireo bairdi).

This is why knowing about subspecies is vital to the average birder, and it simply comes down to two words, splitting and lumping.

Splitting is when a subspecies has become distinct enough, whether genetically, morphologically, or behaviorally, that it is now classified as its own species. I discussed this in my article 10 Facts About The Barred Owl, where the Cinereous Owl (Strix sartorii) was split as its own species in 2010 after being considered a subspecies of the Barred Owl after 136 years. If you want to learn more about this, I highly recommend checking out that article!

Lumping is the reverse of splitting, where a species once considered unique gets reclassified as a subspecies to an existing group. A perfect example of lumping is with the Great White Heron.

Today in North America, there are two members of the Ardea genus, the Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias) and the Great Egret (Ardea alba). However, in 1835, John J. Audubon described a third member that existed solely in the Florida Keys, the Great White Heron (Ardea occidentalis).

Unfortunately, in 1973, the Great White Heron was deemed to not have enough unique genetic markers and showed too much evidence of mixed breeding pairs with Great Blue Herons to classify it as a separate species from the Great Blue, so it became the subspecies Ardea herodias occidentalis.

Unsurprisingly, there has been a huge pushback from the birding community to reinstate the status of species to the Great White Heron. Doing so would make it easier to protect the roughly 1,000-2,500 herons spread across the Florida Keys and other Caribbean islands by listing them as an endangered species.

So, when looking at the importance of listing subspecies, it is essentially a potential free-lifer if it is split from its parent species. However, there is also the possibility that a species you spent hours tracking through rough terrain could be stolen from you if it gets lumped back into another species.

This constant change and fluctuation across species lines is science at work. There have been massive improvements to the field of genetics over the past fifty years, and there will likely be improvements over the next several decades to continue refining our understanding of the taxonomic categories we have today.

So, over the next tens, hundreds, or thousands of years, future scientists might find that the Cozumel subspecies of the House Wren has a noticeably longer bill, distinctly unique song repertoire, and enough genetic differences to warrant its status changing to the Cozumel Wren (Troglodytes beani).

The best part, for me, is it wouldn’t cost me another trip to the island or sweating in the jungle to find the Cozumel Wren since I’ve already listed the subspecies, and it will simply update to the new species, adding a free-lifer to my list!

Why Do Taxonomic Categories Matter?

Returning to our Cozumel birding, we discovered the Yucatan Woodpecker (Melanerpes pygmaeus) is commonly called the Pygmy Woodpecker on the island. This is because it is smaller than the similarly adorned Golden-fronted Woodpecker (Melanerpes aurifrons), and likely due to the pygmaeus species name of the smaller woodpecker.

These different common names are why scientific binomial names are so necessary. It’s essential to note that both common names, Yucatan and Pygmy, describe that species adequately, but its universal binomial, Melanerpes pygmaeus, remains standard across every language and dialect.

So yes, while sifting through minute details might be monotonous and using Greek and Latin might seem absurd, we must have clear lines to understand the relationships between species. It’s almost poetic that this dead language is the universal method of describing nearly every living thing on Earth.

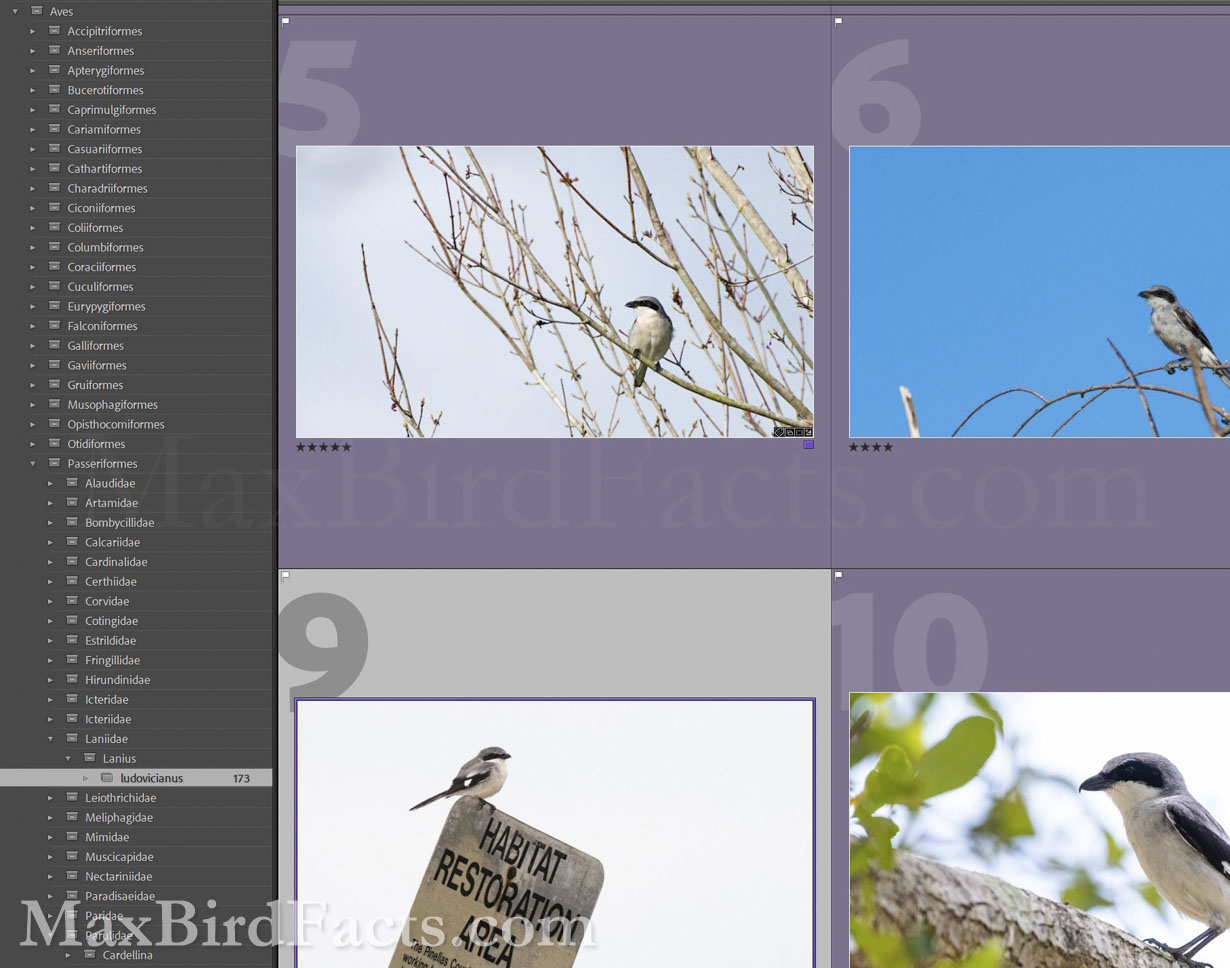

Even for a typical birder or wildlife photographer, taxonomic categories are a useful tool. I’ve reviewed all of my images (currently 40,351) and marked them with keywords for their species in Adobe Lightroom.

After this, I made collections based on the Linnaean classification system to organize my images. So, when I write an article on a specific species or family of birds, I can simply go to its corresponding collection and access all of my images for that subject in one place.

It might seem confusing why I labeled these collections in their Latin names, but I find it much easier to locate the species I’m looking for. For instance, if I were to use the term New World Wood Warblers rather than Setophaga, I would have wasted 14 additional characters to convey the same meaning.

Additionally, if I were to give this library of collections to another birder, my use of “New World Wood Warblers” might mean something different to them than it does to me when the genus name Setophaga is universal.

Again, this is why taxonomic categories matter; regardless of what I consider the common name of Setophaga, its scientific meaning is the same globally.

Labeling and categorizing all of my photos has even led to some additional lifers I likely would have never realized.

Going through old photos from trips where birds weren’t the primary focus and only a few shots in passing netted me a Pigeon Guillemot (Cepphus columba) in the waters surrounding Alcatraz Island in 2009 or a Marbled Murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus) and Rhinoceros Auklet (Cerorhinca monocerata) off the coast of Ketchikan, Alaska while fishing for salmon and halibut in 2013.

So, if you do a lot of birding now and did some photography in the past when you weren’t as into the birds, it might be worth giving those old images a look for a potential life bird.

Now We Know Taxonomic Categories!

So, now we know and better appreciate what taxonomic categories are and why they are important.

Their extensive use to categorize all life on Earth is vital to understanding it and how we fit into this planet. This categorization can be as broad or narrow as you need it to be, whether that is a bird versus a mammal or what makes a House Finch distinct from a House Sparrow.

We now know there are dozens of subsections to each layer of the classic Linnaean classification, and these distinctions are vital to birders.

The difference between groups within a species could lead them to become a subspecies and eventually split into their own species. Or, a group that was once thought to be a distinct species might be found to be more similar to a more established group and get lumped back into that larger species and become a subspecies, like with the Great White Heron.

Finally, keep that mnemonic in mind if you ever have trouble remembering the order of the Linnaean classification system:

- Dear (Domain)

- King (Kingdom)

- Philip (Phylum)

- Came (Class)

- Over (Order)

- For (Family)

- Good (Genus)

- Soup (Species)

I really hope you enjoyed learning about Taxonomic Categories! I know this article had a lot of scientific terms, but I feel that everyone should have a functional understanding of this subject to better appreciate and understand the world we are a part of.

If you have ideas or suggestions for topics you would like me to write about in the future, feel free to leave a comment below or shoot me an email!

If you enjoyed this article, please subscribe to my email list to be the first to know when I post new articles!

Get Outside & Happy Birding

Max

Discover more from Welcome to MaxBirdFacts.com!!!

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.