Sandhill Cranes (Antigone canadensis) sleep in partially or fully submerged ground. Their favorite places are flooded fields, slow-moving rivers, and marshes.

Cranes sleep in these saturated areas because they have lost the ability to perch on branches.

That might sound strange; a nearly 4-foot tall bird would be very obvious sleeping on the ground. Not sleeping up in a tree also puts the birds at a greater risk of predation.

The reason they sleep in these areas is because of their feet. And, just like real estate, location is the key to where they call it a night.

The purpose of the crane’s reduction of the hind toe is a fascinating story of adaptation and natural selection.

We are about to dive into some avian anatomy, so get ready for some sciencey-sounding words!

Bird Foot Basics

The foot is one of the most functional parts of a bird’s anatomy.

Because they gave up their forelimbs for flight, a bird has to use its beak and feet to manipulate objects.

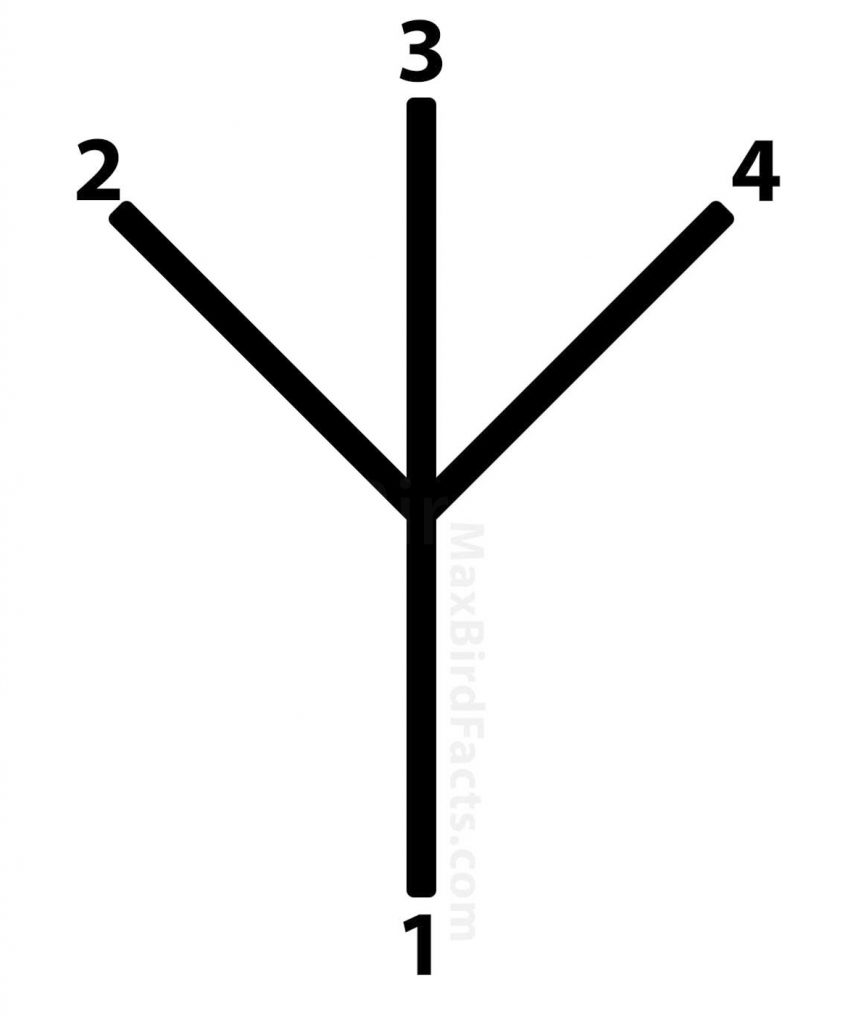

Let’s look at the graphic below to get a feel for a more “standard” bird foot.

This foot style is called anisodactyl and is the most common foot type you will see with birds.

To visualize this, open your hand with your fingers are splayed out. Tuck in your pinky and rotate your thumb backward. Now your hand is in the same orientation as an anisodactyl bird foot.

Your thumb is toe 1, your index finger is toe 2, the middle finger is toe 3, and the ring finger is toe 4. This trick is something I learned in my Ornithology classes to remember the different foot types quickly.

There are nine main foot types seen in avians and many variations within each of those. I have future articles planned for these, but for now, let’s focus on anisodactyl.

Virtually all birds have four toes, similar to how most mammals have five digits on their fore and hind limbs. However, these numbers can vary from species to species because of the animal’s needs and selective pressures (ostriches have two and horses have one).

The ordering of the toes starts with the hind toe, also called the hallux. This is equivalent to how your fingers and toes are numbered, with your thumb or big toe being digit number 1.

The first phalanx rotated from the front of the foot to the back over millions of years of evolution. This change gave early birds more stability when perching in trees.

This perching ability is one of the hallmarks of the biggest order of birds, Passeriformes. Therefore, these avians are commonly called “Perching Birds” or “Songbirds.”

The hind toe is vital to perching. A tendon runs from the toes and through the leg. As the bird squats onto the branch, the tendon is pulled tight and forces the foot closed.

The three forward-facing digits work in conjunction with the hind toe to clamp down on the branch.

This mechanism of tendons allows the bird to stay perched without using much energy to hold on. It also stops them from falling out of the tree when they fall asleep.

Now that we understand the importance of the hallux, let’s talk about why Sandhill Cranes threw it away.

Why Lose the Back Toe?

A crane’s foot is distinctly unusual compared to most other birds.

Sandhill Cranes have reduced their hallux to a residual appendage, meaning this digit no longer holds a functional role or use for the bird.

The hallux has three bones: one metatarsal and two phalanges. The toe ends with a keratinous sheath that covers the distal-most phalanx bone, called the claw or talon. It is the shortest toe on any bird, similar to your thumb being the smallest finger on your hand.

This size difference is even more drastic in cranes. The hallux has become diminished to a dewclaw.

The position of the toe itself has moved further up the crane’s leg, making this toe’s only function to get wet in the morning dew, hence the name “dewclaw.”

It still retains the bone and claw structure we see in other birds, but this toe is all but useless.

There is a reason for this new characteristic. Because of the lifestyle, Sandhill Cranes have the cost of having this toe outweighed its benefits.

Cranes spend almost all of their time on the ground foraging, fighting, dancing, and trumpeting.

Standing at 4 feet tall and having a 6.5-foot wingspan, these are impressively large birds. They are the second largest in Florida, only being outdone by their larger cousin, the Whooping Crane.

Because of their size, cranes don’t have to worry about predators as much, and they can stay on the ground longer.

This continued time on the ground started to alter their anatomy. Cranes stand more upright to see threats easier, and their feet and legs are core to this.

The best way to understand the loss of this hind toe is to look at an ancient relative to all birds, the dinosaurs.

Not all dinosaurs are related to birds, but those that share a lot of similarities.

A bipedal dinosaur’s toe structure is similar to our modern bird’s, with multiple phalanx bones in toes 2, 3, and 4 and only one phalanx bone in toe 1. The dinosaurs also had a claw that ended each distal phalanx.

These claws were dependent on the animal’s lifestyle. For example, they would be more broad and blunt for traction and running or thin and sharp for attacking.

The intriguing thing with dinosaur feet is they are very similar to our crane’s feet.

Dinosaurs, like T-rex, walked on toes 2, 3, and 4 while toe 1 was more residual. This trait seems to be relatively normal with other large, bipedal dinosaurs.

Just like we see in our Sandhill Cranes, the hallux on Tyrannosaurs rex has become residual and moved out of the way.

So why would these two species share this modification to the hallux, even with a 68 million-year gap between them? The simple answer is efficiency.

If you’ve read my other articles on beak anatomy and thermoregulation, you’ll know how crucial efficiency is for birds.

Staying on the ground more and more caused the cranes to have less of a need to perch. In fact, this hind toe would make walking on the ground much more difficult for the bird.

Watching these birds walk, I noticed they draw their foot together as the leg is adducted (pulled towards the body).

If the hind toe was still included in this motion, the crane could accidentally grab objects as it walks. This could then cause the crane to stumble and injure itself as a result.

Let’s think of a raptor. Its hallux is modified to have a firm grip and an extremely sharp talon, nearly the polar opposite of the crane’s.

As the raptor takes off, its foot will start the same closing motion, or at least causing the toes to collect near each other.

For the raptor, this is great. It will give it a better chance of retaining its prey, and the bird can then use its muscle to gain a tight hold on its victim.

Let’s use your hand as an example again.

Hold your arm out and let your hand and wrist fall limp. Your fingers should all be pointing toward the ground, with your thumb being roughly an inch from your other fingers.

This is the natural state of the foot when it is adducted, and to extend the hallux away from the other toes would require energy.

For a bird that needs to walk on the ground while foraging constantly, this would be much less helpful.

If the crane kept the hallux, it could be picking up sticks, rocks, or other objects that would reduce its efficiency while walking.

If it didn’t want to do this, the crane would have to flex the muscle or tendon attached to the hallux with each step.

I think this is the main reason for the reduction in the Sandhill Crane’s hind toe.

And, obviously, other birds with intact and functional hind toes do walk on the ground. So if other birds can still manage to walk and hop on the ground but still perch in trees, why do cranes not?

The first thing to consider is the crane’s size. Remember, Sandhill Cranes are roughly 4-feet tall and have a 6.5-foot wingspan.

These dimensions would make it very difficult for the bird to find a limb with enough headspace to be comfortable. And once the crane is ready to take off from the branch, they need a massive clearance for their wings.

Even if the crane did find a comfortable space to sleep and take off, its size would make it nearly impossible to navigate through the canopy’s branches.

The Sandhill Crane’s size is probably one of the most influential deciding factors on its loss of the hallux.

So once the cranes have ruled out the ability to sleep in trees, the perching mechanism is all but useless. Couple this with the issues the hind toe could cause while walking on the ground, and it becomes very apparent why cranes so quickly abandoned it.

The crane’s feet were formed perfectly for terrestrial life through natural selection over millions of years of random mutation.

Now that we understand why the hind toe is reduced, let’s find out why Sandhill Cranes sleep in the water.

Standing in a Water Bed

Because of the functional loss of their hallux, the cranes cannot perch on a branch. So, if a Sandhill Crane did land on a limb, it would only be standing on it because it has lost the perching mechanism we discussed with Passeriformes.

Nighttime can be one of the most dangerous for an animal. Nocturnal predators come out and can easily sneak up on a sleeping bird.

Sleeping on the ground makes this even more dangerous. The cranes are now at risk from dogs, cats, coyotes, cougars, bears, bobcats, and a whole slew of other threats.

So how do you stay safe from predators without hiding in branches? The solution Sandhill Cranes came up with was to sleep in the water.

It’s actually an ingenious and straightforward way to fix their problem.

If a predator tries to sneak up on a crane, it will create both noise and vibrations when walking through the water.

The sound of it stalking in the water is usually enough to alert the birds, but the ripples it sends as it moves can also be detected by the birds through their legs.

Sandhill Cranes will congregate in the tens of thousands to sleep in the Platte River during the spring migration.

This stopover has been a staple of the crane’s migration for nearly their entire existence, and it almost entirely has to do with its location.

In central Nebraska, the Platte River Basin is home to the largest migration of vertebrate life in all of North America. Hundreds of thousands of Sandhill Cranes will use this area as a stopover during their 3,500-mile migration from southern Texas to the northern reaches of Canada and Alaska.

The cranes have been returning to this river every year for the past 10,000 years because of its perfect location.

The portion of the Platte River the birds take advantage of is ideal to fit their needs. It is almost flawlessly in the middle of their migratory path, surrounded by endless amounts of food, and provides a safe place to sleep.

The river itself is very slow-moving, broad, and shallow. The depth these birds seem to prefer to stay in is just below the ankles, roughly 1 to 2 feet deep.

This depth is enough to keep the cranes safe from would-be predators, but also not so much that they could be swept away.

The Platte River’s width also allows these massive hoards of Sandhill Cranes to gather together.

And during the peak of migration, thousands of birds can huddle into a single mass that looks like an island at first glance.

These gray, feathery masses are an even better deterrent for predators. The thought of having to face thousands of massive birds with spears for beaks and razor-sharp talons would make even the most desperate attacker reconsider.

Once they’ve reached their destination, their habitat stays much the same.

Wetlands and marshes are the preferred areas to make a nest, giving the parents a sort of alarm system. It is challenging for a predator to sneak up onto a pair of cranes in these shallow waters, and that is why they choose them.

Another benefit to residing in these environments is the ability for the cranes to survey over a large area.

A Sandhill Crane might be the tallest object in the wetland or field for miles when standing upright, virtually turning each crane into a watchtower.

Their height is matched by their incredible eyesight, being able to spot a prowling coyote or curious photographer hundreds of yards away and take flight.

Where Do Sandhill Cranes Sleep? Now We Know Where and Why!

Sandhill Cranes sleep in shallow water because of their strange feet. Their feet are such a unique feature to these birds and are central to their entire lifestyle.

The reduction of their hallux allows them to walk and forage more efficiently. If the crane still had this hind toe, it could pick up objects as the bird steps, causing it to stumble.

This loss of the hind toe came with the tradeoff of no longer being able to perch.

Because of this, Sandhill Cranes chose to sleep in shallow water. Sleeping in these damp areas allows the birds to stay protected from predators at night.

In addition, if a predator tries to sneak up on the crane, the sound of it moving and the vibrations it causes in the water will alert the bird.

Sandhill Cranes are easily one of my favorite birds. They have so many unusual features that make me love them more and more each time I see them.

Thank you for reading through this article. I hope you learned something new from it, and all the anatomy terms weren’t too much to handle!

If you have any suggestions for future articles or topics you would like me to dive into, please leave a comment or shoot me an email.

Make today great!

Max

Discover more from Welcome to MaxBirdFacts.com!!!

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Whooping Crane vs. Sandhill Crane – 2 Critical Distinctions To Memorize – Welcome to MaxBirdFacts.com!!!

We have a baby walking the property with mom and dad. Baby is probably 6 inches tall and is

orange.

Learned so much from the story.

The family passes by out lanai about 5:30 or so. pm. Rain or shine.

Noises they make are deafening but welcomed. We know they are approaching.

We sit on an 8 acre lake with lots of reeds all around the lake for their safety and comfort at bed time..

Thanks

Thank you so much for your comment, Joe!!! I’m really glad you learned some new information about these fascinating birds from my article, and I’m so delighted that you get to watch that little colt grow up and they are in a safe environment!

I have seen a sandhill crane standing in pond water up to its belly over the last week, in the early morning hours. I don’t drive by later so I thought it might be stuck since I see it every morning. So glad I found your article and now it makes sense, it is actually sleeping in a safe place rather than the open pasture or woods nearby. I learned a lot from your article (had no idea about the toes) and I also feel relieved that he’s getting a safe night’s sleep and not in any danger.

Thank you so much for commenting Nancy! I’m glad you’re feeling relieved about your local cranes now and learned about their toes. They should be getting out of the water at or just after sunrise to go out and forage. We’re also starting to enter the nesting season, so you may want to keep an eye out for nests and colts coming soon. Thank you again for commenting, and I hope you find some more fascinating birds around you!

Thanks so much for reminding me about nesting season! You were right on the money! Only a few days after seeing your reply, I happened to drive by the pond in the afternoon for the first time. The crane was still there, but another adult was with it. So I thought, well maybe they’re watching over a nest if they’re still here mid-day and still in the same spot. Sure enough, the very next morning when I drove past, there were 2 cranes and two tiny rust-colored fuzz balls! Now I see them all every once in awhile in the pasture near the pond. They are so cute, I have to giggle when I see them!

That’s so great, Nancy!!! I’ve seen a handful of crane families this season, and I always smile when I see a little colt running under their parent’s legs. I’m so happy you get to watch those little guys grow up!

Pingback: Do Sandhill Cranes Mate For Life – The Strength Of Love – Welcome to MaxBirdFacts.com!!!

Very interesting! Thank you! I’m in NE now, my first crane watch experience. Went to the ‘bridge’ at Ft Kearney Recreation area at sunset last night. The winds were fierce – about 30 mph and we saw massive flock of cranes in the sky but none landing in the river… those of us congregating on the bridge speculated the cranes would not roost in the river in this high high wind… but it struck me that an open farm field would be just as windy… any thoughts where cranes might roost in such windy conditions?

Thank you for commenting Mary Anne! I think with those winds the cranes might be concerned with waves in the river that could topple them in the night. I would imagine they had to do a risk evaluation of waves in the river versus coyotes in the fields, and it seems like the risk of waves was higher than coyotes. Fantastic question!

Thank you for this article. I like the way you explained the science and your ideas. It is interesting and can be understood. My husband and I share your love of birds. I think the Sandhill Cranes are fascinating beautiful birds. We have several that return to our small pond each year. They walk through our neighborhood in and out of our yards. One of them was born by our pond. It It had a bent beak. That’s how we know it is the same crane that has grown up and returned to our pond for 3 years. We live about 4 miles from where your retention pond picture in Union Park, Fl was taken. Thank you again.

Thank you, Norma!! You definitely have a nice little hotspot for them at that pond if they’ve returned 3 years. And if you’re in the area for Union Park, you definitely need to go out to the Orlando Wetlands if you haven’t already. Massive bird activity out there and tons of gators too!

I have some sand hill cranes that come by in the morning and an evening I feed them corn because they seem to eat it what else does the sandhill crane’s eat

Corn is one of the crane’s favorites, but they aren’t particularly picky eaters. Insects are a great delicacy for them, so mealworms or crickets would be a great source of protein. Do try not to allow these animals to associate humans with food, though. This association could cause them to react unnaturally to humans and potentially harm the birds. If you provide them with a nice grazing area of native plants and prey, this will be the most natural way to interact with these fantastic creatures.

Pingback: What Do Sandhill Cranes Eat – Eating Bugs For Growth – Welcome to MaxBirdFacts.com!!!

Wow! Brilliant explanation and detailed article that explains the cranes unique characteristics. We’ll done. Great photos, as always and loved the graphic too. I found myself shaping my hand for an example as I read. Great article!!!

Thank you so much!!!