Bird bones are NOT hollow. The definition of hollow is “an unfilled space,” according to Merriam-Webster.

Bird bones are pneumatized. Pneumatic or pneumatized means they are filled with tiny air pockets.

The internal spiderweb-like structure of bone projections creates these air pockets and provides considerable strength.

Birds take advantage of this available space and use it for respiration. Air sacs used for breathing are directly connected to the pneumatized bones.

Because of this, birds are much more efficient at breathing than other animals. The costs of flight necessitate this efficiency.

The problem with this utility is if a bone is broken and connected to an air sac, blood can fill the sac and cause the bird to drown. This is a primary concern when handling birds, especially banding them.

Besides the air sacs, birds also store marrow within their bones, just like mammals. This tissue is essential in producing red and white blood cells.

Red blood cells carry oxygen throughout the body, while white blood cells fight off disease.

So, now that we know bird bones aren’t hollow, let’s dive into arguably the biggest misconception about the avian skeleton.

Are Bird Bones Fragile?

The pneumatized structure of bone provides an incredible amount of strength compared to weight.

Think of the use of rebar or steel mesh in construction. Before concrete is poured, an internal steel composition is added to supports, walls, or other load-bearing structures.

The steel inside the concrete helps give the structure a little more flexibility while also providing a massive improvement in strength. In addition, this steel skeleton distributes the load more evenly throughout the concrete, making it much more durable.

The pneumatization of the bird’s bones is acting in precisely the same way. In addition, the random arrangement of spindly bone provides a surprising amount of flexibility.

So, in this way, if the bird is attacked or runs into something, the bone can give somewhat before it completely breaks.

If we compare a bird’s bone to a mammal’s bone, the avian bone is much stronger.

When looking at similarly sized bones from a mammal and a bird, the bird will undoubtedly win. Mammalian bone is most often composed of an outer layer of dense, compact bone and packed with marrow-filled cancellous or spongy bone.

This structure is robust and sturdy, but it comes at the cost of weight. Marine mammals use this extra weight to their advantage, utilizing their bone density as a ballast.

And this extra weight and density are necessary for the movement of terrestrial animals. Spending time walking and running puts a lot of strain on bone, so these thick walls of compact bone are crucial.

The misconception of a bird’s bones being fragile is not entirely false. Because of their small size, they can easily break and fracture.

However, they are more flexible because of the pneumatization while being more sturdy than expected for their size.

Both bird and mammal bones contain marrow, but mammal bones are pretty hollow once this marrow is removed. The strength behind mammalian bones is from their thick walls.

The lack of flight means our bones can be much denser than an animal that needs to soar.

Birds needed to retain bone strength but cut a massive amount of weight for more efficient flight. The pneumatization of bird bones was the solution to this need.

This internal lattice of bone gave enough structural support that the compact bone could be reduced substantially, allowing the birds to be significantly more efficient at flight.

Fully terrestrial and aquatic avians possess heavy bones, and this would make sense. If the bird has lost its need to fly, it would be better off having stronger bones to survive the threats it will face on the ground.

There are always trade-offs with any transaction. For example, birds traded the thicker walls of compact bone for the lighter and still very sturdy pneumatized bone.

Another fascinating adaptation birds have undergone to both save weight and strengthen their skeletons is bone fusion.

Fusing or losing bones isn’t a new thing for animals. For example, the ancestors of horses walked on four toes, while modern horses only stand on their middle toes.

Birds have used this fusion to significant effect, though. For instance, many diving birds have fused the furcula (wishbone) to their sternum (keel bone).

This fusion gives these birds a tremendous amount of strength in this area, and for a particular reason. When a bird dives in pursuit of a fish, the head, neck, and chest will take the brunt of that impact.

If the furcula weren’t attached to the sternum, this bone would break from the repeated impacts with the water.

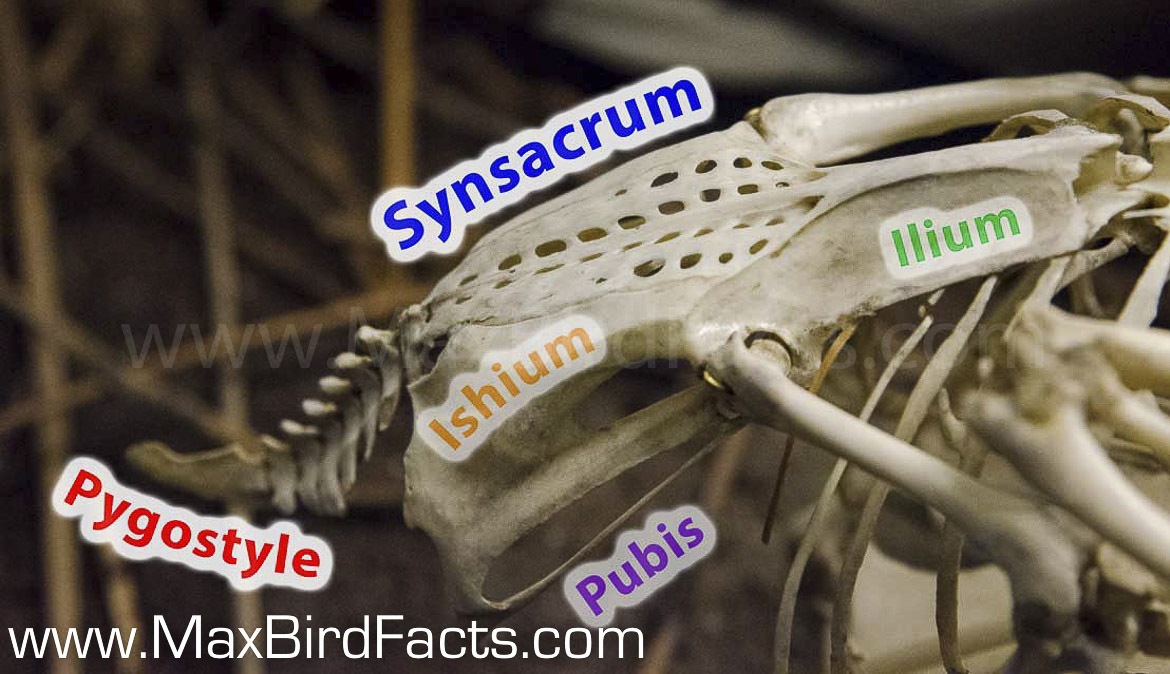

Looking further down the skeleton, two prime examples of fusion are the pygostyle and synsacrum.

The pygostyle, formed by the caudal vertebrae, provides a solid anchoring point for a bird’s tail feathers and associated muscles.

The fusion of 1 thorasic, 2 sacral, 6 lumbar, and 5 caudal vertebra form the synsacrum. It is a crucial muscle attachment for the legs and tail, keeping these stable during flight.

The synsacrum is further fused to the ilium. All of this connection creates a very robust pelvic girdle.

Avian Injuries

Suppose a bird bone is fractured, damaged, or even broken. In that case, the bone can heal substantially faster than expected because of calcium redistribution.

Calcium redistribution pulls the mineral from healthy bone and uses it to repair damaged areas.

I talk about calcium redistribution a lot in my article Why Do Birds Eat Eggshells – Calcium Redistribution & Bone Repair, so if you want to learn more about that, I would strongly recommend you check it out.

This process is vital for birds; quick repair of bone can mean the difference between hunting or starving.

Even with calcium redistribution, some broken bones can be so severe that it can sometimes lead to that animal’s death. The leading cause of this would be starvation, but it also can be caused by blood getting into the bird’s lungs if that bone is connected to a major air sac.

For that reason, you should never attempt to handle a bird unless you know what you are doing or with someone who does.

I’ve volunteered at a banding site where I was fortunate enough to release an Ovenbird after it was banded. The importance of correctly holding the bird was a huge deal; too tight and you might crush the bird; too loose and the bird can injure itself struggling.

The method I was shown was to hold the bird’s head between my right index and middle finger and use my left hand to support the bird’s body. The right thumb, ring finger, and pinky are all lightly holding the wings to the bird’s body. Then, when releasing the bird, you have to extend all the fingers on the right hand and let it take off.

If you see an injured bird on the ground, call the local Audubon society. I was on vacation in Maryland and saw a woman helping a Chimney Swift fluttering on the ground.

I went over and helped her pick it up, and showed her the correct way to hold the bird so it wouldn’t hurt itself. Then, finally, I instructed her to put the swift into a box lined with soft material and let it rest.

I searched for the number of the local Audubon chapter and got them in touch with the woman. She was able to get the swift to an animal rehab center. Thankfully the only injury the swift had was a torn rotator cuff and not a broken bone.

It was great to help this little guy out and share some knowledge with Daisey. (If you’re reading this, I hope you’re doing well!)

Why Are Bird Bones Hollow? They Aren’t!

Now we know that bird bones aren’t hollow; they are filled with air sacs and marrow.

The pneumatization of avian bones allows them to be much more efficient with respiration and provides an extraordinary amount of strength compared to their weight.

This connection of air sacs to the bone does cause some complications if the bone is damaged or broken.

Fusion is a great way for birds to increase the strength of their bones while also saving weight. These fusions might be a standard feature for all birds, like the pygostyle and synsacrum. While others are purpose build, like the fusion of the furcula to the sternum.

I want to stress this again unless you know how to handle a bird, please don’t. You could cause the animal more stress and injuries. Instead, call someone who is experienced and wait for their help or guidance before continuing.

It was a lot of fun writing this article and hunting down some of my photos to use in it. If you have any suggestions or ideas for future articles, please let me know in the comments below!

Get Outside & Happy Birding!!!

Max

Discover more from Welcome to MaxBirdFacts.com!!!

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I don’t know anyhing special about birds, but what I do know for a fact, is that concrete does not gain any fexibility is you put some steel rods in it. Concrete is basiclly less dense stone and stone does not bend whatsoever. The rebar is there to provide stabillity and help with the consturction of larger room. Concrete is easily pulled apart by gravity under it’s own weight so the rebar is there to take that pressure from the concrete.

Very interesting, thanks for clearing that up. I definitely know more about birds than concrete and rebar, so I appreciate the input!